By Andrew George/The Conversation

When I was young, one of my favorite TV shows was M*A*S*H.

Set in a U.S. mobile hospital during the Korean War, the army doctors and nurses approached their work with wacky black humor. As the helicopter ambulances brought in the wounded to the tented Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH) near the battlefront, they were triaged and patched up before being sent on to larger hospitals. This is a model for treating the wounded that was largely developed by a French surgeon, during the Napoleonic wars. He was Baron Dominique Jean Larrey, born 250 years ago this month.

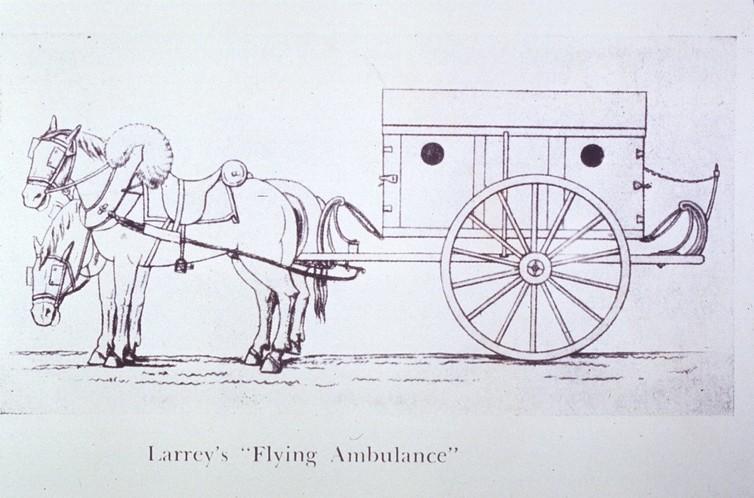

Larrey, who fought in most of Napoleon’s campaigns, believed in rapid treatment of the wounded, and invented the first ambulance.

These horse drawn “flying ambulances” could maneuver rapidly across the battlefield, picking up injured men and taking them to field hospitals just outside the battle zone. There the soldiers would be treated, and when stable, sent to hospitals behind the lines, often based in convents or monasteries.

The National Library of Medicine

The National Library of Medicine

Larrey worked tirelessly to provide good medical support for men in his care. He constantly battled a military administration, who often saw the wounded as unwanted mouths to feed. He fought incompetence and quartermasters who sold the supplies needed by hospitals for personal profit. And he argued with generals who would prefer resources to go to front-line operations.

Although Larrey often made himself very unpopular, he had the support of the Emperor Napoleon, who had a great regard for him, possibly in part because he realized the positive effect he had on troop morale.

Baron Larrey, irinaraquel/flickr, CC BY

Baron Larrey, irinaraquel/flickr, CC BY

Larrey had strong principles. He developed triage, so that the wounded were treated in order of need, regardless of rank or nationality. While this did not endear him to all generals or administrators, in the long run it saved his life.

Wounded and captured by the Prussians after the battle of Waterloo, he was about to be shot when the medic tying the blindfold recognized him. He was sent to the Prussian general, Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher. Larrey had saved Blücher’s son’s life after a previous battle and, following dinner, was released with money and an escort.

Innovative, Skilled Surgeon

As well as a fantastic administrator and a brave man, Larrey was an innovative and skillful surgeon. He promoted rapid amputation as he saw it led to better survival than the standard delay. For conventional amputations, he used three circular cuts to form an inverted cone, which, for legs, produced a stump that fitted wooden legs well. This compared very favorably to the alternative, a straight cut with the tissue then being pulled down and sewn over the end of the bone; resulting in pain, frequent infection and gangrene.

Larrey was one of the few surgeons who could successfully undertake disarticulation (separation of two bones) at the hip or shoulder joint, and amputation at the shoulder joint is sometimes still known as Larrey’s amputation. During 1812 he noted that he could reduce the pain of amputation by packing the stumps with snow.

He also operated on civilians. If anyone wants a reason to give thanks for the development of anesthetics, they should read the account by novelist Fanny Burney of her mastectomy that Larrey did without the benefit of drugs.

Complex, Vain, Virtuous

He was a complex person. He kept his hair long, because he felt physically and mentally ill if it was cut too short. He picked fights because of perceived slights, and railed against the Establishment when he did not get honors or jobs that he felt due to him. He was a committed revolutionary republican, who led 1,500 students in the storming of the Bastille, but adored Napoleon even as he assumed the title of Emperor.

He was vain, claiming that at Waterloo the Duke of Wellington had ordered the artillery not to fire in his direction. He then doffed his hat. According to the anecdote, the Duke of Cambridge asked the Duke of Wellington who he was saluting. “I salute the courage and devotion of an age that is no longer ours,” he replied. This touching story is only slightly marred by the fact that the Duke of Cambridge was not at Waterloo.

However, Larrey was much loved. There are many stories of ordinary soldiers putting themselves at risk to save his life. In the panic-stricken crossing of the Berezina River, during the retreat from Moscow, they passed him over their heads across the bridge jammed with fleeing soldiers.

He was also one of relatively few people that Napoleon recognized in his will, leaving 100,000 francs to “the most virtuous man I have known.”

Larrey died in 1842 in Lyon, at the ripe age of 76, rushing back to Paris from an inspection of military hospitals in Algiers to see his sick and much beloved wife, Charlotte. She sadly died three days earlier.

But Larrey’s influence lives on. Next time you see an ambulance weaving through the traffic, remember the man who invented its predecessor, which galloped around the battlefields of Europe.

–

Andrew George is the deputy Vice-chancellor at Brunel University London.

–

Comments welcome.

![]()

Posted on July 13, 2016