By Gamal Abdel-Shehid/The Conversation

The Toronto Raptors have succeeded in establishing themselves as a major cultural and economic player in both the city of Toronto and beyond, with several offshoots of the outdoor fan zone Jurassic Park popping up in the suburbs and across Canada. The Raptors have cemented themselves into the fabric and psyche of the city, with Raptors gear flying off the shelves.

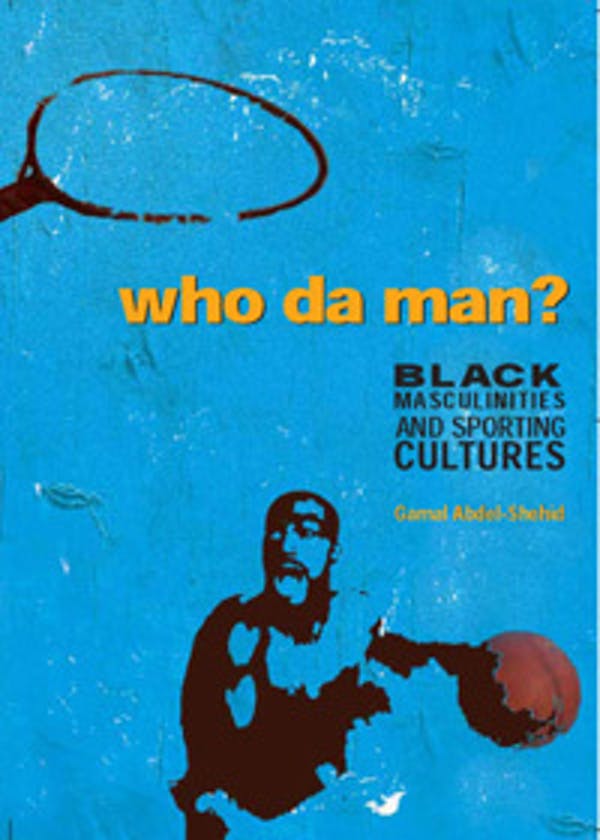

The Raptors have also succeeded in telling their story from the point of view of individuality and hard work. These are themes I wrote about 15 years ago in my book, Who Da Man?: Black Masculinities and Sporting Cultures, which was based on what is probably the only scholarly article written about the Toronto Raptors, “Who Got Next? Raptor Morality and Black Public Masculinity in Canada.”

In Who Da Man?, I tried to understand sports outside of its own narrative. That means that I didn’t want to look solely at the fan’s perspective on things; instead I looked at what sports, and the Raptors, meant from a sociological, or let’s say deeper, point of view.

I argued that the arrival of the Raptors in the late 1990s in a hockey town constituted an attempt to construct an American version of Black masculinity and individuality, which I called Raptor Morality, in Canada. Raptor Morality refers to a mentality that puts forth a “determined Black male who is fiercely individualistic and committed to a dream of ‘making it’ through the brutal channels of professional sport.”

To make my argument, I looked at the Raptors from a deeper lens than the one the media usually takes, which is to focus solely on the game. In doing so, I consulted the work of several Black writers, most of whom had nothing to do with sports, including people like African-American novelist and essayist James Baldwin and Canadian writer and poet Dionne Brand. These writers gave me a chance to see Black life beyond basketball.

I teach the text in my fourth year class on Sport, Race and Popular Culture. The feedback from my students, most of whom wear Raptors gear and hail from municipalities like Brampton and Scarborough, is that they appreciate the fact that you can examine the Raptors, and sport, from a different (not necessarily better) lens than the one the media takes, which only focuses on the sport itself or the positive effects of the sport on the city.

Multicultural Teamwork

To some extent, the Raptor Morality I wrote about still exists. Maybe it has to exist. Perhaps high-performance athletes have to be fiercely individualistic to deal with such brutal realities as making it through the channels of high performance sport, something the classic documentary Hoop Dreams showed us years ago.

But the morality on display in 2019 is to the Raptors’ credit. For example, the Raptors are an example of both individualism and a kind of multicultural teamwork both on and off the court.

For one, not only have the Raptors succeeded in showcasing the incredible diversity of Toronto, that diversity (while not perfect) has now become a draw for many African-American NBA players. It’s no wonder Charles Barkley called Toronto “my favorite city.”

The main players in the Raptors’ story in 2019 are not only a multicultural tour de force but also represent certain ethics beyond individualism. Masai Ujiri, the team president, is a Nigerian-Canadian who runs a charity called Giants of Africa and has been central in establishing a presence for the NBA there. The level of Ujiri’s charitable activity is unusual and laudable for someone in his position.

Pascal Siakam soars to the hoop over Andre Iguaodala during Game 1 of the NBA Finals in Toronto/Gregory Shames, The Canadian Press

Pascal Siakam soars to the hoop over Andre Iguaodala during Game 1 of the NBA Finals in Toronto/Gregory Shames, The Canadian Press

So it’s no accident that two of his best players are from Africa. Serge Ibaka is from the Congo – and part Spanish. Pascal Siakam is from Cameroon. Ujiri personally scouted Siakam years ago at a Basketball Without Borders camp. Siakam’s rags-to-riches story, and his level of dedication to Cameroon and Africa more broadly, is also commendable. It is also, understandably, one of the main storylines of this postseason, and exemplifies the new Raptor Morality.

Another multicultural angle is represented by superfan Nav Bhatia, a Sikh car dealership owner from Mississauga who has attended every home game in the Raptors’ 24-year history. If that’s not enough of an accomplishment, Bhatia has launched the Nav Bhatia Superfan Foundation to give back to the community through basketball. In addition, he has recently become a spokesman for racial tolerance, given the recent racist abuse he received in Milwaukee during the Eastern Conference Finals and his highly commendable decision to confront his abuser with a gesture of peace.

Finally, there is Drake: ambassador for the Raptors and, in the eyes of many, the city. Drake has used his Afro-Jewish heritage to signify his belief that Toronto is wonderfully unique and superior to American cities. To this end, Drake’s mission – borne out in the recent documentary The Carter Effect – has been to represent his city.

All told, this is the story of Raptor Morality in 2019, almost 25 years after the team first began playing. It’s a truly sentimental time for fans of the team. Many of the team’s icons have embodied hard work and beating the odds, but also a dedication to greater causes than basketball. As much as the on-court success, it’s translated into a groundswell of civic pride previously unseen. It is a marvel to watch.

–

See also:

This is fantastic. Read through the thread. Great stuff.. https://t.co/DwaqibWjSJ

— Steve Kerr (@SteveKerr) May 27, 2019

–

Gamal Abdel-Shehid is an associate professor in the School of Kinesiology and Health Science at York University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

–

Comments welcome.

Posted on June 7, 2019