By Roger Wallenstein

Before there was the Dominican Republic, Panama, Venezuela, Mexico or Puerto Rico, there was Cuba.

As in professional baseball, in which Cuba led all Caribbean and South American countries in 1878 with the inception of the Cuban League. That’s just one little tidbit from César Brioso’s Last Seasons in Havana: The Castro Revolution and the End of Baseball in Cuba. With today’s absence of the game formerly known as the National Pastime, a baseball fix is welcome, and Brioso’s tome has been preferable to watching the Korean League at 5 a.m.

Of course, the presence on the White Sox roster of Cubans José Abreu, Yoán Moncada, Luis Robert and catcher Yasmani Grandal, who emigrated from Cuba at age 10, continues to pique my interest in Cuban ballplayers going back to the early ’50s when Minnie Miñoso was the most exciting and talented player in town.

For almost 70 years the South Side club has featured many Cubans such as shortstop Alexei Ramírez (2008-15) and pitcher José Contreras, who went 15-7 for the 2005 champions and holds the club record of 17 straight wins. In what has to be a Top 10 highlight in team annals, we won’t soon forget Orlando (El Duque) Hernández. Pitching in relief in the series-clinching ’05 ALDS against Boston, he entered the sixth inning protecting a one-run lead with the bases loaded and no outs. Two pop-ups and a strikeout later, El Duque’s magic propelled the local Sox to a 3-0 sweep of the series.

There were other Cubans starring for the White Sox long before El Duque, who spent just that one season on the South Side. Sandalio (Sandy) Consuegra pitched three years for the Sox including 1954 when he was 16-3, and teammate Mike Fornieles became a stalwart of the team’s bullpen at that time.

Summer In Winter

Winter baseball in Cuba featured four teams, Havana, Almendares, and Marianao, all located within the capital city, and Cienfuegos, 230 miles to the southeast. As a kid, a few games every winter were beamed back to the States so we could watch in black and white.

Each club was limited by Major League Baseball to three non-Latino big leaguers. Some general managers didn’t want their players, whether Latin or not, participating in winter leagues where they had little control. Brioso writes that White Sox GM Frank Lane prohibited Miñoso from playing soon after Minnie joined the Sox. Other GMs also stopped their Latin stars from playing, which cut into the Cuban League’s attendance.

However, in 1955, delegates from the Caribbean Confederation came to an agreement with MLB to relax those rules whereby native players like Miñoso could play in Cuba in the winter and expanding non-Latin participation as well.

And play they did. For instance, take a guy like Cuban pitcher Pedro Ramos, who toiled for the inept Washington Senators and then Minnesota Twins when the team moved in 1961. Ramos led the American League in losses four straight seasons (1958-61) despite an ERA of a not-so-horrible 3.91. He averaged just shy of 258 innings pitched in those four seasons.

When we saw Ramos on TV playing winter ball in Cuba, we simply considered him a mediocre pitcher who gave up a lot of home runs for losing teams. Even the fact that he hurled another 190 frames for Cienfuegos the winter of 1958-59 for a total of 449 between April and February – his combined record was 10-31 – wouldn’t have impressed us in those days long before pitch counts and Tommy John surgeries.

The guy who did make an impact was Ramos’s teammate and fellow Cuban Camilo Pascual, who pitched for the Senators-Twins from 1954-66 in an 18-year big league career that saw him win 174 games. Pascual was known for his curveball. As far as right-handers go, he was in a class with Hall of Famer Bert Blyleven. Sandy Koufax, a southpaw, arguably had a most intimidating 12-to-6 curveball, but for righties, Pascual was right up there.

Pascual had a breakout year in 1959 when he went 17-10 for a Senators team that finished last, 31 games behind the pennant-winning White Sox. That winter, pitching for Cienfuegos, Pascual posted a 15-5 mark and an ERA of 2.01. He added two more wins in the Caribbean World Series – Cienfuegos represented Cuba – for a 34-15 record over a 10-month period. You won’t see anything like anytime soon if ever.

Black And White

At the start of the 20th century, white players from Cuba began to appear in the major leagues. Miguel (Mike) González, a catcher, debuted in 1912 and played 17 seasons in the National League. The biggest Cuban star and first Latino pitcher in the first half of the century was Adolfo (Dolf) Luque (pronounced loo-kay), who won 194 games over 20 seasons, starting in 1914. In 1923 pitching for Cincinnati, Luque went 27-8 with a 1.93 ERA. He also pitched a couple of innings against the White Sox in the infamous 1919 World Series, and Luque won a game for the Giants in the 1933 Series, becoming the oldest pitcher to do so at age 42. Camilo Pascual credited Dolf Luque with teaching him to throw the curveball.

Of course, Black Cubans like Miñoso, who appeared in nine games for Cleveland in 1949, wouldn’t wear a Major League uniform until after Jackie Robinson broke the barrier in 1947. However, Black players were welcomed into the Cuba League beginning in 1900 following the war of independence from Spain. Slavery ended on the island in 1886, so it took but 14 years for Blacks to be accepted into professional baseball in Cuba compared to 82 years in the U.S.

Stars from the Negro League flocked to Cuba in the winter. Many of the great Black players of the era like Cool Papa Bell, Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige and many others joined teams in Cuba while future major league regulars Monte Irvin, Sam Jethroe, Don Newcombe and Hank Thompson came later.

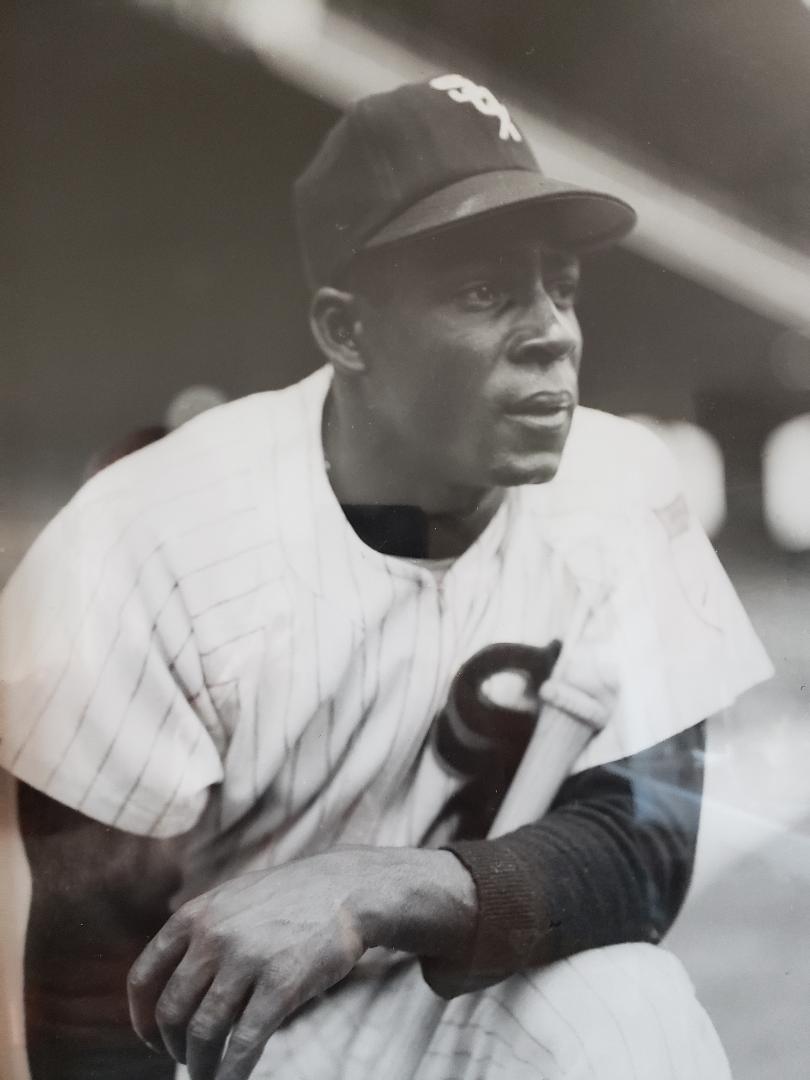

Minnie Miñoso, in a photo hanging on a wall in Roger Wallenstein’s home

Minnie Miñoso, in a photo hanging on a wall in Roger Wallenstein’s home

Being a native Black Cuban, Miñoso occupied a unique position in baseball history. Writing in his autobiography Baby Bull, Puerto Rican Hall of Famer Orlando Cepeda, whose first MLB season was 1958, claimed Minnie “is to Latin ballplayers what Jackie Robinson is to black ballplayers. As much as I love Roberto Clemente and cherish his memory, Minnie is the one who made it possible for all us Latinos. Before Roberto Clemente, before Vic Power, before Orlando Cepeda, there was Minnie Miñoso. Minnie is the one who made it possible for all us Latins . . . He was the first Latin player to become a superstar.”

Sugar Kings

Havana occasionally was mentioned as a possible major league franchise prior to expansion in 1961. Beginning in 1954, the city had a Triple-A International League team, the Sugar Kings, an affiliate of the Cincinnati Reds. The roster was sprinkled with Cubans like shortstop Leo Cárdenas and pitcher Mike Cuellar both of whom had long major league careers.

However, once Castro’s revolution overthrew the Batista regime, officials in the U.S. got a bit nervous, to say the least, as U.S.-Cuban relations soured. In the middle of the 1960 season, the Sugar Kings morphed into the Jersey City Jerseys. They left Havana on a road trip and never returned.

On the heels of the Sugar Kings’ exit, the Cuban Winter League ceased operation after the government created a sports federation, ending professional baseball in Cuba.

This was 60 years ago, but the stream of Cuban players continued to flow through defections and human trafficking. Thirty Cuban-born players were listed on MLB rosters at the start of the 2019 season – compared to 102 from the Dominican Republic.

José Abreu, a Cienfuegos native who hit .341 over 10 seasons in the Cuban national league, has never divulged the details of his leaving Cuba to sign with the White Sox. Other Cubans like Aroldis Chapman have chilling stories. He walked out of a hotel in 2009 in the Netherlands where the Cuban team was playing in an international tournament, got into a waiting car, and left behind his entire family in Cuba to play baseball in the United States. Chapman’s family eventually was permitted to leave the island although the details – no doubt involving a chunk of the $100 million Chapman has made pitching baseballs – have never been disclosed.

Finally, a bit more than two years ago, MLB and the Cuban Baseball Federation came to an agreement whereby Cuban players would not have to defect to play in this country. Up to 20 percent of signing bonuses would go to the Cuban Federation, and players would be treated like those coming from Japan, South Korea, or Taiwan.

However, the Trump administration canceled the agreement last year, recreating a situation where defections and human trafficking could ignite once again. Commissioner Rob Manfred vowed to stand by the deal.

A week from Friday the White Sox are slated to being the fan-less, 60-game season cobbled together amid the global pandemic. It will look nothing like any season in history. What will look familiar is a Sox lineup that includes Abreu, Grandal, Robert and Moncada (if he tests negative for COVID-19), who will continue the long line of Cuban players on the South Side beginning with Minnie Miñoso 69 years ago.

–

Former Bill Veeck bar buddy Roger Wallenstein is our White Sox correspondent. He welcomes your comments.

Posted on July 13, 2020