By Ellis Cashmore/The Conversation

On October 2, 1980, Muhammad Ali, then aged 38, and Larry Holmes, the heavyweight champion of the world, entered a temporary arena built at Caesar’s Palace, Las Vegas. A gate of nearly 25,000 had paid $5,766,125, a record in its day. “It wasn’t a fight; it was an execution,” wrote Ali’s biographer Thomas Hauser. After 10 sickeningly one-sided rounds, Ali’s trainer Angelo Dundee signaled Ali’s retirement. Ali’s aide and confidante Bundini Brown pleaded: “One more round.” But, Dundee snapped back: “Fuck you! No! . . . The ballgame’s over.”

In a way, he was right: one game had indeed finished. Ali fought only once more. His health had been deteriorating for several years before the ill-advised Holmes fight and the savaging he took repulsed even his sternest critics. Ali the “fearsome warrior,” as Hauser calls him, would disappear, replaced by a “benevolent monarch and ultimately to a benign venerated figure.”

And now that venerated figure has died, aged 74.

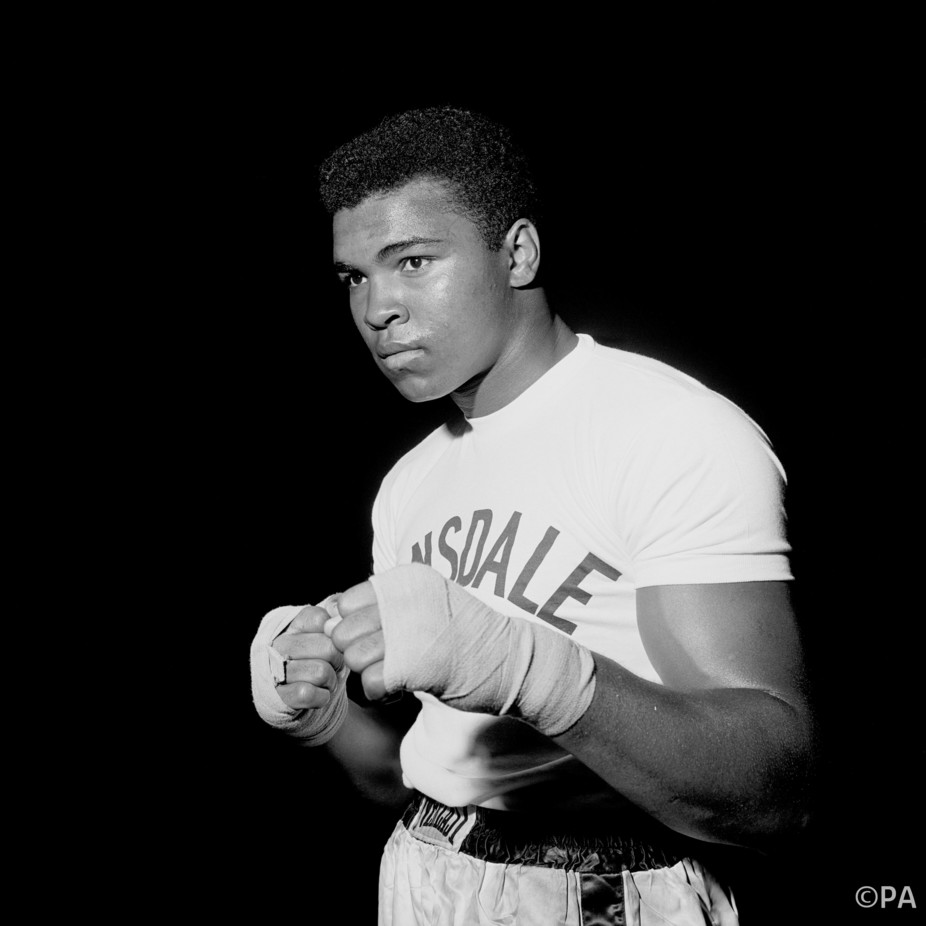

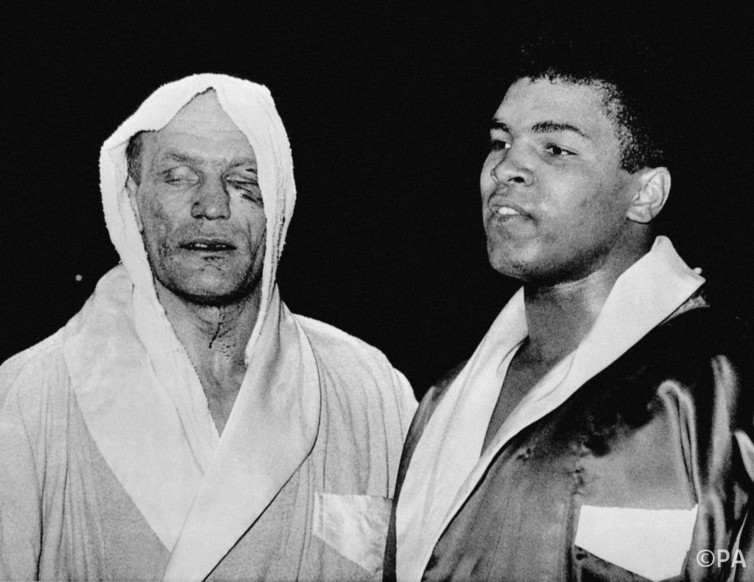

Photos: PA Archive

Photos: PA Archive

Muhammad Ali was also a symbol of black protest, a cipher for the anti-Vietnam movement, a martyr (or traitor, depending on one’s perspective), a self-regarding braggart, and many more things beside. While there have been several sports icons, none have approached Ali in terms of complexity, endowment and sheer potency. Jeffrey Sammons suggests: “Perhaps no single person embodied the ethic of protest and intersected with so many lives, ordinary and extraordinary.”

Born Into Two Nations

Born in Louisville, Kentucky, in the segregated south, Cassius Clay, as he was christened, was made forcibly aware of America’s “two nations,” one black, one white. After winning a gold medal at the 1960 Rome Olympics, he returned home to be refused service at a restaurant. This kind of incident was to influence his later commitments.

Clay both infuriated and fascinated audiences with his outrageous claims to be the greatest boxer of all times, his belittling of opponents, his poetry and his habit of predicting (often accurately) the round in which his fights would end. “It’s hard to be modest when you’re as great as I am,” he remarked.

He beat Sonny Liston for the world heavyweight title in 1964 and easily dismissed him in the rematch. Between the two fights, he proclaimed his change of name to Muhammad Ali, reflecting his conversion to Islam. While he’d made public his membership of the Nation of Islam (NoI), sometimes known as the Black Muslims, prior to the first Liston fight, few understood the implications. The NoI was led by Elijah Muhammad and had among its most famous followers Malcolm X, who kept company with Ali and who was to be assassinated in 1965.

Among the NoI’s principles was a belief that whites were intent on keeping black people in a state of subjugation and that integration was not only impossible, but undesirable. Blacks and whites should live separately; preferably living in different states. The view was in stark distinction to North America’s melting pot ideal.

Ali’s commitment deepened and the media, which had earlier warmed to his extravagance, turned against him. A rift occurred between Ali and Joe Louis, the former heavyweight champion who was once described as “a credit to his race.” This presaged several other conflicts with other black boxers whom Ali believed had allowed themselves to become assimilated into white America and had failed to face themselves as true black people.

Sting Like A Bee

The events that followed Ali’s call-up by the military in February 1966 were dramatized by a background of growing resistance to the U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. Ali’s oft-quoted remark “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong” made headlines around the world. He insisted that his conscience not cowardice guided his decision not to serve in the military and, so, to many others, he became a mighty signifier of pacifism. To others he was just another draft dodger.

At the nadir of his popularity, he fought Ernie Terrell, who, like Patterson, persisted in calling him “Clay.” The fight in Houston had a grim subtext with Ali constantly taunting Terrell. “What’s my name, Uncle Tom?” Ali asked Terrell as he administered a callous beating. Ali prolonged the torment until the 14th round. Media reaction to the fight was wholly negative. Jimmy Cannon, a boxing writer of the day wrote:

“It was a bad fight, nasty with the evil of religious fanaticism. This wasn’t an athletic contest. It was a kind of lynching . . . [Ali] is a vicious propagandist for a spiteful mob that works the religious underworld.”

Wilderness Years

Ali’s refusal to serve in the armed forces resulted in a five-year legal struggle, during which time Ali was stripped of his title. During his exile, Ali had angered the NoI by announcing his wish to return to boxing if this was ever possible. Elijah, the supreme minister, denounced Ali for playing “the white man’s games of civilization.” He meant sports.

Other evaluations of sport were gathering force. The black power inspired protests of John Carlos and Tommie Smith at the 1968 Olympics, combined with the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa, had made clear that sport could be used to amplify the experiences of black people the world over. While Ali was a bête noir for many whites and indeed blacks, several civil rights leaders, sports performers and entertainers came out publicly in his defense. He was hailed as their champion.

Given the growing respect he was afforded, he was seen as an influential figure. Ali’s moves were monitored by government intelligence organizations; his conversations were wiretapped. But the mood of the times was changing: he was widely regarded as a martyr by the by-then formidable anti-war movement and practically anyone who felt affinity with civil rights.

His years of exile over, he returned to boxing. But prospect of a smooth transition back to the title was dashed March 1971 by Joe Frazier, who had taken the title in Ali’s absence and defended it with unexpected tenacity in a contest that started one of the most virulent rivalries in sport. Ali had called Frazier a “white man’s champion” and declared: “Any black man who’s for Joe Frazier is a traitor.” Ali lost once to Frazier and beat him twice over the following years, every fight being viciously fought.

Ali had to wait until 1974 before getting another chance at the world title. By this time, Ali, at 32, was not favored; in fact, many feared for his well being against the hitherto unbeaten George Foreman. The fight in Zaire became immortalized as “The Rumble in the Jungle” and Ali emerged again as champion.

In June 1979, Ali announced his retirement from boxing. At 37, he appeared to have made a graceful exit when he moved to Los Angeles with his third wife Veronica whom he had married two years before. His first marriage lasted less than a year ending in 1966; Ali married again in 1967, again in 1977 and then in 1986 to his current wife Yolanda Williams.

Hauser estimates Ali’s career earnings to 1979 to be “tens of millions of dollars.” Yet, on his retirement, Ali was not wealthy.

Within 15 months of his retirement, Ali returned to the ring, his principal motivation being money. He also made several poor business investments and, while prolonging his sports career seemed suicidal, he managed one more fight, again ending in defeat. He was 39 and had fought 61 times.

In 1984, he disappointed his supporters when he supported Ronald Reagan’s re-election bid. He also endorsed George Bush in 1988. The Republican Party’s policies, particularly in regard to affirmative action programs, were widely seen as detrimental to the interests of African Americans and Ali’s actions were, for many, tantamount to a betrayal.

Ali’s public appearances gave substance to stories of his ill health. By 1987, he was the subject of much medical interest. Slurred speech and uncoordinated bodily movements gave rise to several theories about his condition, which was ultimately revealed as Parkinson’s syndrome. His public appearances became rarer and he became Hauser’s “benign venerated figure.”

Over a period of five decades, Ali excited a variety of responses: admiration and respect, but also condemnation. At different points in his life, he drew the adulation of young people committed to peace, civil rights and black power; and the anger of those pursuing social integration.

Ali engaged with the central issues that preoccupied America: race and war. But it would be remiss to understand him as a symbol of social healing; much of his mission was to expose and, perhaps, to deepen divisions. He preached peace, yet aligned himself with a movement that sanctioned racial separation and the subordination of women. He accepted a role with the liberal Democratic administration of Jimmy Carter, yet later sided with reactionaries, Reagan and Bush. He advocated black pride, yet disparaged and dehumanized fellow blacks. He taught the importance of self-determination, yet allowed himself to be sucked into so many doubtful business deals that he was forced to prolong his career to the point where his dignity was effaced. Like any towering symbol, he had very human contradictions.

–

Ellis Cashmore is a visiting professor at Aston University. This article was originally published on The Conversation.

–

See also: Song Of The Moment: Black Superman.

–

Comments welcome.

![]()

Posted on June 4, 2016