By Danielle McLean/The Hechinger Report

RIO GRANDE VALLEY, Texas – Adelyn Vigil sometimes dreams of volleyball.

The 13-year-old imagines the arm movements, the sound of the ball hitting her hand. Not an aspiring star, Adelyn has enjoyed volleying the ball, informally, but doesn’t really know how to play the game. But her friends do, and she simply would like to be part of a team.

“Whenever people play sports, it looks so fun,” said Adelyn. “It looks like they are just enjoying themselves.”

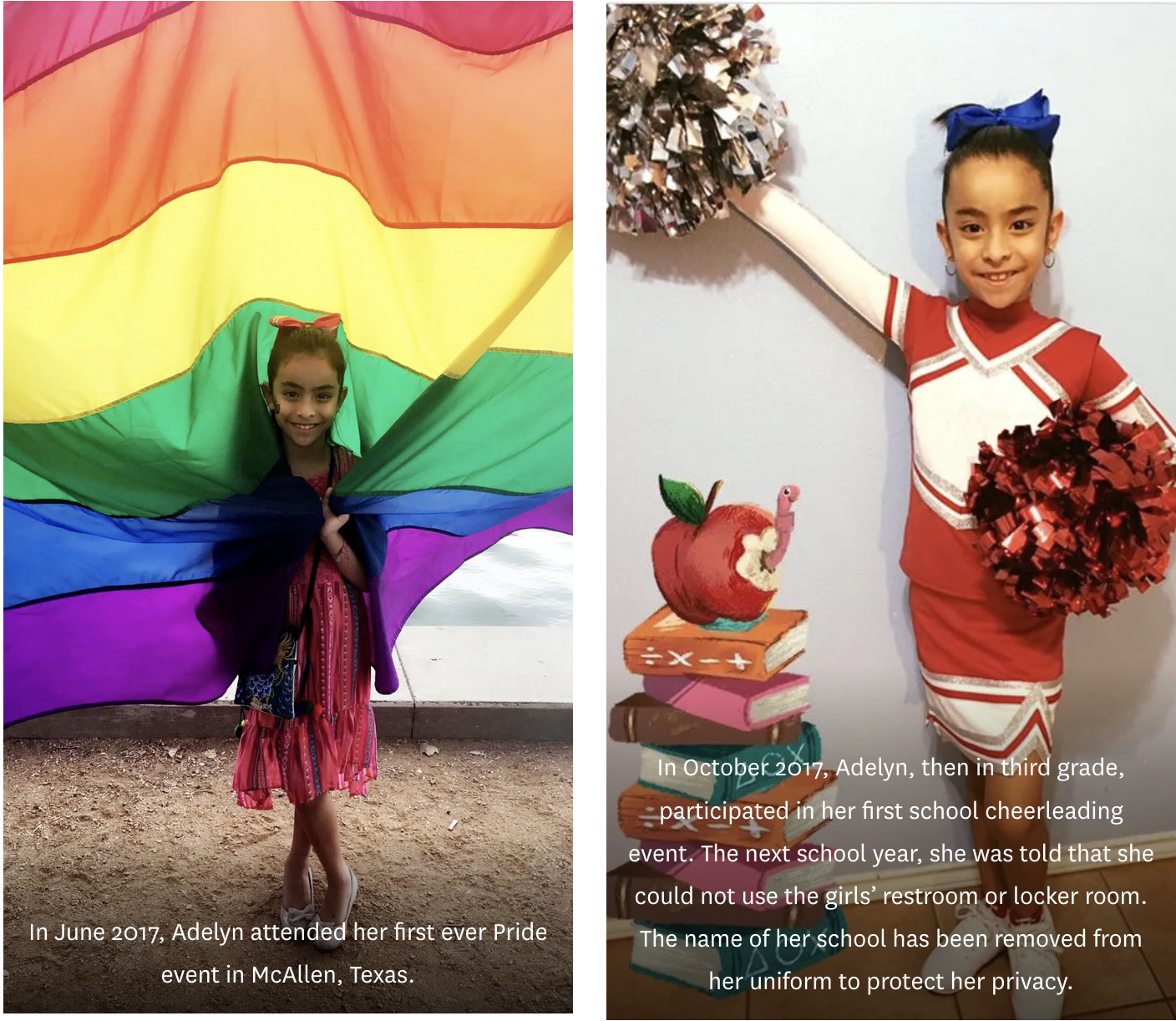

She is not sure playing on a sports team will ever happen for her, though. A trans girl living along the Mexican border in Texas’s Rio Grande Valley, Adelyn once participated in school-based extracurricular activities, like cheerleading and poetry club. But she dropped them when she was told by school administrators that she could not use restrooms or locker rooms that corresponded with her gender identity.

Adelyn Vigil/Verónica G. Cárdenas for The Hechinger Report

Adelyn Vigil/Verónica G. Cárdenas for The Hechinger Report

Though officials eventually reversed their stance, the stress and humiliation have taken their toll.

“We pretty much walk on eggshells every school year, just waiting to see how they are going to be reacting or what’s going to change this year,” said Adamalis Vigil, Adelyn’s mother.

To protect her privacy, The Hechinger Report is not naming Adelyn’s school district or the city where she lives. When contacted, the school district said that it addressed problems immediately and in accordance with federal and state law, and that neither Adelyn’s family nor her legal counsel have offered any additional concerns.

“In anticipation of a new school year, the district still remains prepared to meet a consecutive time with the student’s legal guardian and counsel to ensure all parties involved continue to be treated equally and fairly under local, state and federal laws,” the district said, in a statement.

But state law may be about to change. As Adelyn started eighth grade this year, Texas lawmakers were considering shutting the door to sports participation for trans students at all grade levels.

Currently, state policy says that birth certificates are the official determinant of a student-athlete’s gender. However, the state permits its citizens to amend birth certificates, as Adelyn has. Lawmakers are considering a bill that would forbid the body that oversees extracurricular activities in the state from considering amended birth certificates.

In June, Adelyn said she was not getting her hopes up that she would be able to play in the upcoming school year. She’s been crushed too many times in the past, she said.

“Just let me play sports,” said Adelyn, rolling her eyes. “I’ve been wanting to play volleyball for forever . . . Come on, it’s not hurting anyone.”

The bill did not pass during the legislature’s regular session or in two special sessions called by Gov. Greg Abbott, a Republican. Currently, the proposal is under consideration during a third special session, but as the debate has ground on, Adelyn decided not to participate in volleyball no matter what the legislature decides. The anxiety and fear were too much to take on, her mother explained.

“Her privacy was completely disregarded,” Vigil said, referring to the way Adelyn was treated by the district in the past. “She’s scared that other parents are going to complain and make a big deal of it, and she will be embarrassed.”

And playing on boys’ teams is out of the question.

“Well, I’m not a boy,” Adelyn explained, dumbfounded by the very idea. “Not only would I not like it and get very uncomfortable, but I would get very bullied. Very bullied.”

Plus, she added, a lot of men in the Rio Grande Valley think they’re better than women and wouldn’t let her play with them, anyway.

“I don’t know what goes on in their little pea brains,” she said with an annoyed sigh.

For Adelyn and other trans students, the trauma goes beyond debates in the state capital over bills that put their basic rights at risk. Over her time in school, she’s been kept out of girls’ locker rooms and bathrooms. When she was in sixth grade, she was told she could not take physical education, and school staff shifted her to a dance class – Adelyn wore her dance leggings under her clothes to avoid the locker room. School personnel eventually relented, and removed these restrictions, but unlike most other students, Adelyn has been denied or steered away from her right to play at any level by Texas law.

“At the end of the day, we might be able to defeat this bill,” said Ricardo Martinez, the chief executive officer of Equality Texas. “But the wreckage will remain.”

Trans people represent an estimated 0.6 percent of the U.S. population. Middle or high school students who participate in sports make up a tiny portion of this group, and trans girls like Adelyn make up an even smaller segment. Yet trans student participation in sports has recently become a conservative political obsession.

Supporters of bills barring trans students – especially trans girls – from sports say they are needed to protect girls from unfair competition.

Bills that restrict trans students from playing on sports teams that correspond with their gender identity have been introduced in 36 states in 2021 and have passed in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Mississippi, Montana, Tennessee and West Virginia, according to the legislative tracker run by the advocacy group Freedom For All Americans.

The avalanche of bills has been so overwhelming that many trans students who play or wish to play sports have opted not to voice their objections, fearing the publicity and censure that would follow.

But there has been some legal opposition. In 2020, Idaho was the first state to enact a ban on trans girls and women from participating on teams that correspond to their gender identity. But in August of that year, a judge temporarily stopped the state from enforcing the ban until its constitutionality could be determined.

And in late July 2021, a federal judge temporarily halted the implementation of a trans student sports ban in West Virginia. Becky Pepper-Jackson, an 11-year-old trans girl in Bridgeport, West Virginia, challenged the law, saying that it was keeping her from trying out for her middle school’s cross-country team with other girls.

The experience has caused the family a lot of stress, anxiety and “a deeper sadness,” said Becky’s mother, Heather Jackson.

“It just breaks your heart to have to tell your child that they can’t do what they want to do just because of who they are. It’s absolutely devastating,” Jackson said. “My child deserves to live and flourish in our community, and I have to be the one to tell her that she’s not allowed to.”

Adelyn, a native of the Rio Grande Valley region, is the second of three children born to Vigil, and Antonio Jr. Adelyn’s older brother, Antonio III, 17, a high school student, plays baseball, but her younger brother, Allek, 9, does not play any organized sports. Her large extended family lives nearby.

Adelyn declared to her mother at age 3 that she was a girl. When playing, she would wrap her superhero cape around herself like a dress. But it wasn’t until she was 7, when she told her mom that she prayed to God that she would return as a girl after she died, that Vigil embraced her daughter’s gender identity.

Her older brother and relatives adapted quickly, except for one of her grandfathers. But a few months after Adelyn transitioned, he yelled at her to bring him a beer – using her name, “Adelyn.”

“I went and took the beer to him and ran to my mom, ‘Mom! Grandpa used my name!” Adelyn said. It was among the happiest moments of her life, she said.

In those early days, the school transition also seemed to go smoothly. Adelyn was allowed to use the girls restroom without issue.

The next year, when Adelyn was in third grade, she joined the school’s cheerleading team and the competitive Spanish poetry team. But problems arose when she entered fourth grade after a new principal arrived, said Vigil. The school district told her Adelyn couldn’t use the girls restrooms, the girls locker room, or the water fountain located inside. Instead, according to Adelyn, she would have to go to the nurse’s office to use the restroom or to the cafeteria on the other side of the building to get water.

Adelyn decided to quit all after-school activities following the decision by school administrators. At cheerleading, she wouldn’t have been allowed to change with all the other girls. At poetry club, she wouldn’t have been allowed to use the restroom at district-wide competitions against other schools.

“Not being allowed to use your correct bathroom . . . that’s just so embarrassing and humiliating,” Adelyn said.

This type of conflict is common for trans children and youth. Sixty-one percent of trans and nonbinary youth reported being discouraged or prevented from using a bathroom that corresponds with their gender identity in a 2020 Trevor Project survey of over 40,000 LGBTQ youth and young adults.

Adelyn’s school reversed course months later, after pressure from Vigil and the ACLU of Texas. But by that point, she was afraid to rejoin the poetry or cheerleading teams out of fear that her school would change its decision. She suddenly hated school.

The same battle she had fought and won in elementary school came up again when Adelyn started middle school in 2019-20. She was again restricted from using the girls restroom. Vigil said she was never given an explanation.

Adelyn often risked punishment from the school by using the girls restroom during the two minutes between classes when there was chaos in the hallways and before hall monitors began looking out for kids skipping class. She was never caught, but middle school marked the beginning of frequent panic attacks.

And while Adelyn was fighting battles at school, she was also among those squaring off against Texas Republican lawmakers, who were increasingly focusing on restrictions against transgender people. Like other legislators across the country, Texas Republicans are targeting trans people with proposed laws that reach beyond sports. Bills that would restrict the ability of trans people to access medical care have been introduced in 22 states. Other proposals would allow people to use religious objections to deny services to LGBTQ people.

At one April committee meeting that ran late into the night, Adelyn testified against a bill that would punish doctors who prescribed trans youth hormone therapy and puberty suppression treatments or who performed gender-confirmation surgery.

“My family drove five hours to inform you how life-threatening this bill can be,” Adelyn told the committee, her mother at her side. “Not only to me, but to many trans people. As a trans person I believe I should have access to health care I need. I’m sure you can imagine how hard my family works to support me and make sure I have the things me and my siblings need. My health care is private, and I should not have to come here to explain to you that even if you don’t understand it, it is important.”

Adelyn and her mother left the session and immediately headed north to Dallas, where Adelyn receives trans-related medical care. But on the long drive home, Adelyn started crying hysterically, in the grip of another panic attack. Vigil had to slap her across the face to get her out of it.

On that occasion, Adelyn was worried that she would no longer be able to receive the medical treatments needed to support her transition. Vigil said she shared those fears.

“As a mother, that’s the worst feeling ever because I’m supposed to protect my child and I felt like a failure,” Vigil said. “More than anything, I felt powerless because I had the same fears as my child and just like her, I felt hopeless too.”

While Republican lawmakers push for laws banning trans students from sports, hardly any are able to cite examples of trans athletes causing a problem in their states.

The most often-cited example comes from Connecticut. The Alliance Defending Freedom, a conservative advocacy group, filed a lawsuit on behalf of four cisgender women in that state zeroing in on two transgender sprinters, Terry Miller and Andraya Yearwood. Miller and Yearwood had both won several high school state track titles, though one of the cisgender plaintiffs beat Miller in a championship race just two days after the suit was filed.

A federal judge dismissed the case on procedural grounds in April 2021 because both Miller and Yearwood had graduated from high school. But, the ADF argues, the case shows that trans girls have an “insurmountable advantage” over cisgender girls and would destroy fair competition in women’s sports.

However, the question of whether trans women hold advantages over cisgender woman at elite levels of sport is a matter still under intense debate and research. One recent study found that trans women in the U.S. Air Force after two years on hormones had slightly faster running speeds compared to their cis peers, but indistinguishable muscle strength. The authors of the study by the British Journal of Sports Medicine added that more research is needed to determine the athletic impact on trans teens who take puberty blockers and estrogen or testosterone.

Regardless, most high school athletes – which the Texas bill targets – join sports teams for social and health reasons, with far fewer motivated by winning championships or earning college scholarships, said Tom Farrey, executive director of the Sports and Society Program at the Aspen Institute, a global nonprofit dedicated to realizing an equitable society.

Organized sports can help young children develop and improve their cognitive skills and achieve academically with better concentration, attention, classroom behavior, grades, and standardized test scores, according to the Aspen Institute. High school athletes are more likely to attend a four-year college and earn degrees than non-athletes, the Institute found.

Sports have been linked to helping women who hold corporate executive positions achieve success and can improve long-term mental health outcomes of children who have experienced trauma such as sexual abuse, emotional neglect, or parental alcohol abuse.

But sports are also, simply, an important social outlet.

Laura Crossley, a 38-year-old trans woman from Kelowna, Canada, said she decided to play in a local high-level adult women’s ice hockey league in 2019 after moving to the area from Vancouver because she is more comfortable around women than she is around men. She has never really fit in around men, she said.

Crossley, who has been taking hormones since 2016 and started socially transitioning in 2019, has been playing ice hockey since she was 5 years old.

“When I started my formal social transition, I was living in a new community and one of the ways to meet people and get outside my comfort zone was to get back into hockey,” she said.

Crossley understands the benefits that participating on a sports team can have on a young person’s mental health. But while trans people have existed in all cultures throughout history, there has been a recent awakening around their existence over the past decade.

“People don’t want to understand it, don’t want to accept it,” said Crossley. “Instead of having a discussion with the other side, they just put in all these laws.”

Those laws and policies have left children like Adelyn without an important social outlet and have forced many to become advocates about deeply personal issues. Adelyn was left briefly speechless when asked about an assertion from President Trump that women’s sports “will die” if trans women are allowed to participate.

After a brief pause, she finally said: “Since when has he cared about women’s sports and women? Oh my God. I can’t with stupid people.”

After an interview at her home, Adelyn snuggled in her bed with her cousin Aylette, debating whether to get Boba tea or frozen yogurt. Adelyn and Aylette hang out a lot. During sleepovers, they throw on Vigil’s high heels, plug in Christmas lights, and turn Adelyn’s room into a club, dancing to Cardi B and Bad Bunny.

Adelyn is “funny, loving, kind, and a bit crazy,” Aylette said, laughing.

Adelyn sees a future in astronomy, possibly studying the moons, stars and planets – or as a civil rights attorney or a politician.

“I want to make a change,” said Adelyn. “Nobody is going to fight for me. I’m fighting for myself.”

This post was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.

–

Comments welcome.

Posted on October 11, 2021