By Tim McLaughlin/Reuters

The mutual fund giant Fidelity Investments, founded seven decades ago and run ever since by the Johnson family, has won the trust of tens of millions of investors.

The company’s tradition of putting clients’ interests “before our own is a big part of what makes Fidelity special,” the fund firm says in its mission statement.

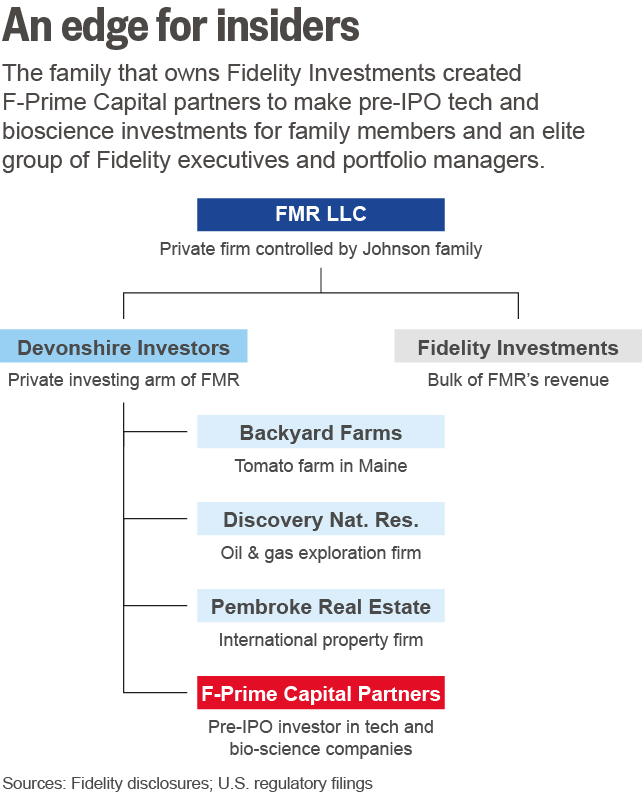

In at least one lucrative field, however, the Johnson family’s interests come first. A private venture capital arm run on behalf of the Johnsons, F-Prime Capital Partners, competes directly with the stable of Fidelity mutual funds in which the public invests. It’s an arrangement that securities lawyers say poses an unusual conflict of interest.

All photos by Brian Snyder/Reuters

All photos by Brian Snyder/Reuters

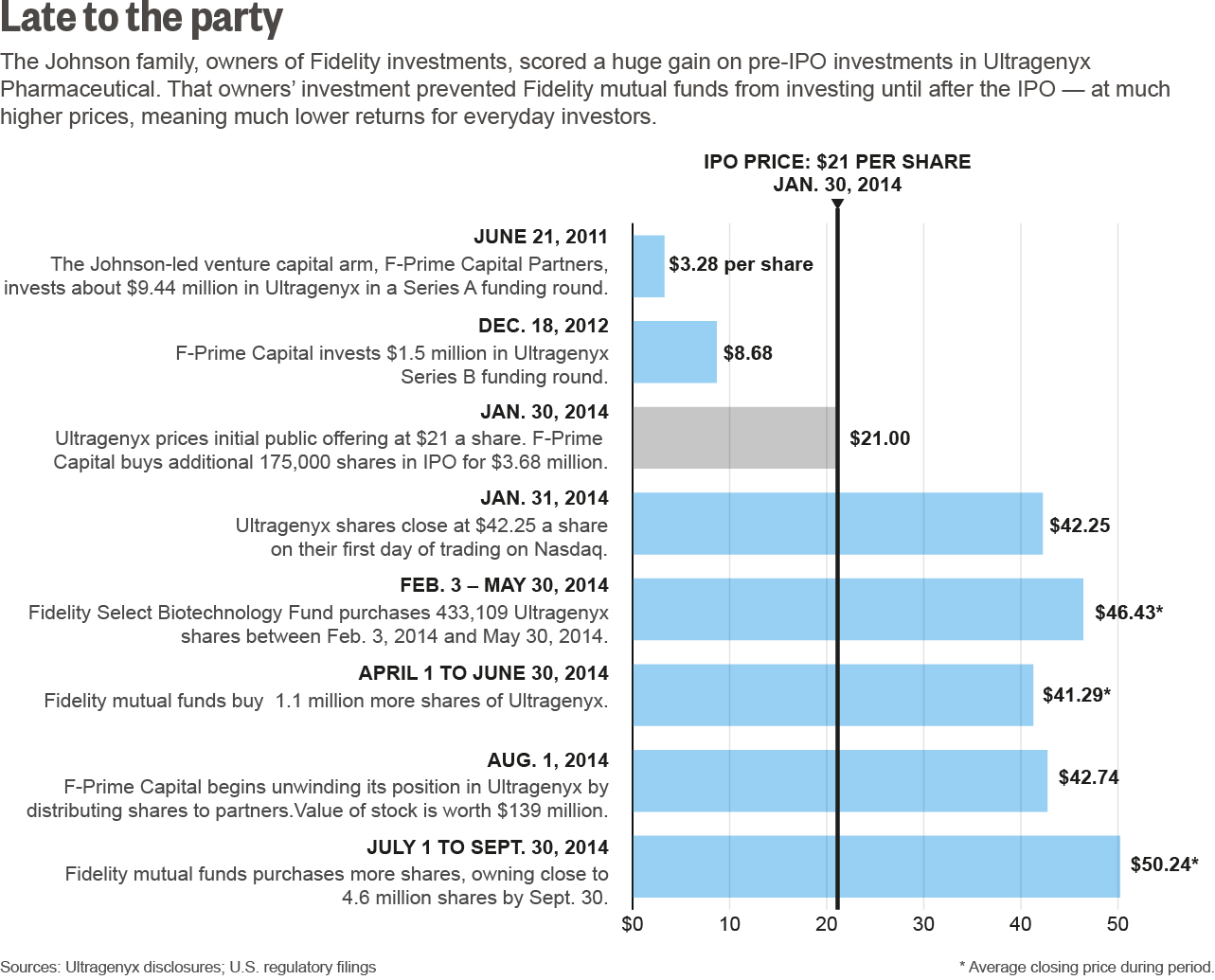

That conflict can be seen in the case of Ultragenyx Pharmaceutical, a promising biotech start-up. In 2011 and 2012, the Johnsons’ F-Prime Capital invested a total of $11 million on Ultragenyx before the start-up made an initial public offering of its stock.

The pre-IPO investment effectively prevented Fidelity mutual funds from making the same play. If both the private fund and Fidelity’s ordinary funds had invested, they would have violated U.S. securities laws, which prohibit affiliated entities from buying substantial stakes in the same companies at the same time.

The managers of Fidelity’s public funds eventually did purchase Ultragenyx shares, but not until after the stock price skyrocketed in the firm’s January 2014 initial public offering. The Fidelity funds bought about 1.1 million Ultragenyx shares in the second quarter of 2014. The average price for the stock was $41.17 during that three-month period – 12 times higher than the $3.55 a share paid by F-Prime Capital.

By the end of June 2014, the Johnson family and an elite circle of Fidelity insiders were sitting on a gain of $128 million – or about 1,000 percent – on the Ultragenyx investment. Several of Fidelity’s mutual fund rivals, including American Funds and BlackRock Inc, did just as well or better on the Ultragenyx play by investing at about the same time as the Johnsons, U.S. regulatory filings show.

–

–

–

Fidelity declined to comment on the specific investments examined by Reuters and declined to detail how it balances the interests of Fidelity funds and the Johnsons’ F-Prime funds in cases where they might compete for the same investment.

Abigail

Abigail

Fidelity’s chief executive, Abigail Johnson, declined to comment for this story.

Yale University law professor John Morley said Fidelity runs the risk of losing investors by competing with the funds that serve them.

“What they’re doing is not illegal, not even unethical,” Morley said. “But it’s entirely appropriate for mutual fund investors to take their money elsewhere because Fidelity has made a decision to take away some of their potential returns.”

Alan Palmiter, a business law professor at Wake Forest University, called the arrangement more problematic because it directly pits the interests of Fidelity fund investors against those of Fidelity’s owners and elite managers.

“It’s hard to imagine a clearer corporate conflict of interest,” Palmiter said.

SEC spokeswoman Judith Burns, a former reporter for Dow Jones who covered the SEC, said the agency could not comment on a specific company.

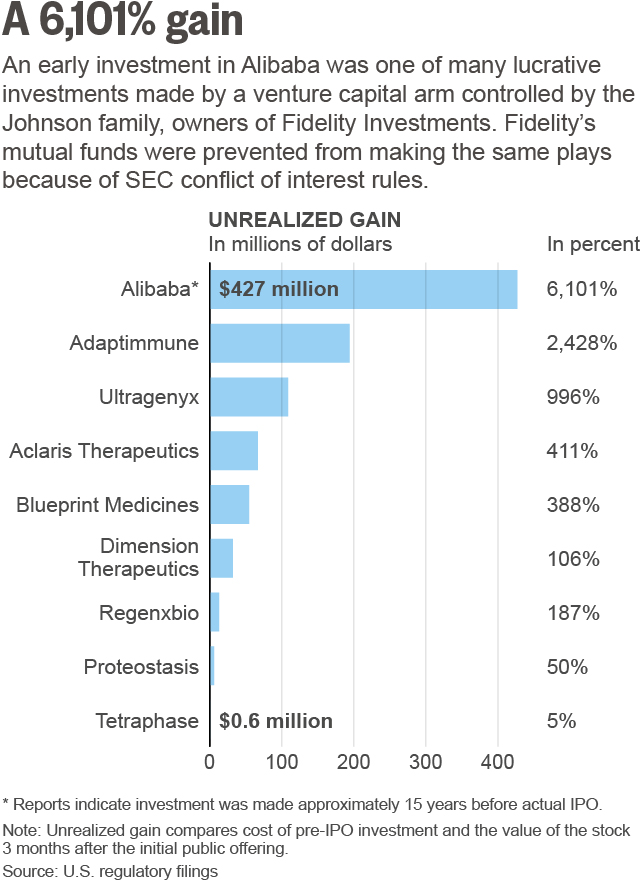

Reuters analyzed 10 pre-IPO investments since the beginning of 2013 by the Johnson-led venture capital arm. The analysis found that, in six of those cases, Fidelity’s mass-market mutual funds made major investments later and at much higher prices than the insiders’ fund, resulting in lower returns for Fidelity fund shareholders.

In the other four cases, Fidelity funds did not invest at all in companies in which the Johnson-led venture arm already had a sizable stake.

Fidelity’s internal guidelines prevent such investments when the Johnsons’ venture holdings are “substantial,” a standard that Fidelity declined to define to Reuters.

The Reuters examination also found:

- Over the past three years, U.S. regulatory filings show, the Johnson-led venture arm has beaten Fidelity mutual funds to some of the hottest prospects in tech and bioscience – including the best performing IPO of 2015.

- Fidelity mutual funds became one of the largest investors in six bioscience and tech companies backed by F-Prime Capital after the start-ups became publicly traded. Legal and academic experts said that major investments by Fidelity mutual funds – with their market-moving buying power – could be seen as propping up the values of the Johnsons’ venture holdings.

- Key compliance executives have held dual roles overseeing investments by Fidelity and F-Prime Capital. For three years until September, the chief compliance officer for Fidelity mutual funds, Linda Wondrack, also served as chief compliance officer for Impresa Management LLC, the advisory firm that manages the investments of F-Prime Capital.

Fidelity’s James Curvey also wears two hats: He chairs a board of trustees that oversees many Fidelity stock mutual funds, and also serves as a trustee for one of the owners of Impresa. Curvey has been involved with the Johnsons’ private investments for more than 20 years and has made millions of dollars from them. - Some portfolio managers for Fidelity’s mass-market funds receive lucrative partnership interests in the private F-Prime funds. Star portfolio manager Will Danoff, for instance, donated $4 million worth of Alibaba Group stock to Harvard University in 2015 that he received through the venture arm for $3,432, according to his family’s charitable foundation.

Fidelity spokesman Vincent Loporchio said Fidelity executives declined to grant interviews for this story. In a written statement, Fidelity said it follows the law relating to potential conflicts of interest between its mutual funds and the venture capital arm.

“We strictly adhere to all legal and regulatory requirements that apply to our management of our mutual funds and other client accounts and our proprietary venture capital investments,” Fidelity said. “Where there is the potential for such investments to overlap, we apply internal guidelines designed to ensure that our mutual funds comply with relevant legal and regulatory restrictions on their ability to acquire securities issued by companies in which Fidelity has a pre-existing proprietary investment.”

Fidelity declined to comment on whether its mutual funds were interested in making the same pre-IPO bets as F-Prime Capital.

Over the past three years, however, the mutual funds have been among the nation’s biggest investors in pre-IPO companies, U.S. regulatory filings show. The pressure on Fidelity to produce market-breaking returns has never been higher. Since the end of 2008, investors have pulled nearly $100 billion from Fidelity’s actively managed mutual funds, while net deposits into Vanguard Group’s index funds approached $700 billion, according to Morningstar data.

Fidelity’s two top rivals, BlackRock and Vanguard, said they do not operate separate investment arms that might compete with their mutual funds. Vanguard Chairman and CEO William McNabb goes a step further, investing almost all of his personal financial assets in Vanguard funds, because he wants to ensure his interests are aligned with those of his customers, said company spokesman John Woerth.

–

–

Johnson family members and Fidelity insiders also own Impresa Management, which runs partnerships and investments on F-Prime’s behalf, overseeing about $2.6 billion in assets, according to SEC disclosures. Impresa’s strategy is to bet on promising bioscience and tech start-ups.

If F-Prime controls 5 percent or more of a private company’s voting stock, then that ownership prevents the Fidelity mutual funds from buying the same security before or during an IPO, according to the Investment Company Act of 1940. Fidelity told Reuters that it concurs with that reading of the law, which is enforced by the Securities and Exchange Commission.

SEC rules aim to ensure that the interests of mutual funds are on at least equal footing with the interests of affiliates, said Joseph Franco, a law professor at Suffolk University Law School in Boston. The rules seek to prohibit a situation where, for instance, a mutual fund might invest in a pre-IPO company at an above-market price with the intent of boosting the value of an earlier, lower-priced investment by an affiliated entity.

The rules also seek to ensure that mutual fund managers are not influenced by the interests of an affiliated entity, such as Fidelity’s in-house venture operation, Franco said.

The law would not prevent purchases of stock owned by an affiliated entity after an IPO, in the open market. But Fidelity said it applies its own guidelines, which prevent such purchases when there is a “substantial” level of ownership by F-Prime. The guidelines are meant to address potential conflicts of interest and questions of fairness for investors in Fidelity mutual funds, the company said.

John Bonnanzio, an editor at Fidelity Monitor & Insight, which makes independent recommendations on Fidelity funds, said the Johnson-led venture investing has been a good way to reward and retain star portfolio managers such as Danoff.

“Hedge funds have siphoned off a lot of good portfolio managers from mutual fund companies,” Bonnanzio said.

HEIR APPARENT

Founded in 1946 by Abigail Johnson’s grandfather, Edward Johnson II, Fidelity’s mutual fund business manages $1.2 trillion in assets. Privately held Fidelity is still controlled by the family and has been the linchpin of their fortune. The clan’s net worth is estimated at $26 billion by Forbes magazine, making them the 9th-richest family in the United States.

Ned

Ned

The founder eventually turned the reins over to his son, Fidelity’s chairman, Edward “Ned” Johnson III, who is now 86. Today, Abigail Johnson, 54, is heir apparent. The oldest of Ned’s three children, Abigail spent her career preparing for the top job, starting at Fidelity as an intern before moving on to portfolio manager and now CEO. She lives in the home once owned by her grandfather.

Abigail and her younger siblings, Elizabeth and Edward Johnson IV, are investors in F-Prime Capital, according to disclosures by the venture fund.

The family’s private investments sometimes dovetail with members’ personal interests. In 1985, Ned Johnson used venture funding to launch a limousine service after it took too long to hail a taxi at Boston’s airport, according to accounts in the Boston Globe. Abigail Johnson’s husband, Christopher McKown, co-founded a healthcare start-up, Iora Health, that has received multiple rounds of investment from F-Prime.

OPPORTUNITY COSTS

Over the years, F-Prime and other venture investing entities have generated billions of dollars in gains for the family and company insiders, according to financial disclosures made by Fidelity.

Ned Johnson has used part of his wealth to amass a collection of antiquities worth nearly $260 million through his nonprofit Brookfield Arts Foundation, according to the charity’s 2014 annual report.

The nonprofit’s purchases include a 200-year-old Chinese merchant house that Johnson had moved from that country and reassembled at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts. The house and its contents are worth $17 million, according to Brookfield’s 2014 disclosure to the U.S. Internal Revenue Service.

Other beneficiaries of the venture investments include top Fidelity officials such as Peter Lynch, the legendary Magellan fund manager and Fidelity vice chairman, and current portfolio managers such as Danoff, who manages about $109 billion in assets at Fidelity’s Contrafund.

The Ultragenyx investment illustrates the opportunity cost Fidelity investors face when a mass-market fund encounters a conflict of interest with F-Prime.

–

(ENLARGE)

(ENLARGE)

–

Ultragenyx was hardly a hidden gem. Several of Fidelity’s rivals, including American Funds, BlackRock and Columbia Management, also got in on the early action before the company’s initial public offering. Columbia’s Acorn Fund, for example, invested $10 million at the same time as F-Prime and had an unrealized gain of nearly 1,100 percent, or $108 million, in mid-2015 before unwinding part of its position, U.S. regulatory filings show.

In the third quarter of 2014, Fidelity funds boosted their collective stake in Ultragenyx by 3.3 million shares to become the biotech firm’s largest mutual fund investor, with nearly 4.6 million total shares. By then, the average closing price of the stock had moved up to $50.24 from $41.17 in the second quarter. During the same quarter, F-Prime unwound most of its stake in Ultragenyx by distributing the stock to limited and general partners, U.S. regulatory filings show.

Asked about F-Prime, Fidelity said in a statement that its mutual funds get priority over the Johnson family’s interests.”When both our proprietary venture capital group and our funds express interest in investing in the same private companies, the funds always prevail,” the company said in a statement.

CONFLICTED REFEREES

One person who has been refereeing potential conflicts between Fidelity and Johnson family investments is Linda Wondrack. Until September, she doubled as chief compliance officer for the mutual funds and for Impresa Management, which manages the F-Prime assets. She served in both capacities for three years.

In September – after Reuters asked whether Wondrack’s dual role presented a conflict of interest – Fidelity hired another executive to replace Wondrack in one of the two positions. The fund appointed a company veteran, Chuck Senatore, a University of Chicago Law School lecturer, as chief compliance officer of Impresa Management.

A single person could not effectively perform both jobs, said Wake Forest University’s Palmiter, who called the arrangement “nearly laughable.”

Wondrack would have felt feel pressure to side with the venture capital arm because her ultimate boss is Abigail Johnson, said Palmiter, who has written extensively on the fund sector and is a critic of its governance standards.

Wondrack, 52, is paid as an employee of Fidelity, U.S. regulatory filings show. She joined Fidelity in 2012, after working at mutual fund company Columbia Management.

Loporchio, the Fidelity spokesman, said the company identified the need for a change in a “periodic review of its processes.”

Another key overseer of Fidelity fund investors’ interests, however, continues to serve in a similar dual role.

James C. Curvey – a long-time top lieutenant of Fidelity Chairman Ned Johnson – is chairman of the board of trustees for a number of Fidelity mutual funds, including ones that invest in the same companies as F-Prime.

Fund trustees are responsible for protecting the interests of investors. Ned Johnson chose Curvey for the role when Johnson gave up his duties as chairman of the board of trustees for individual Fidelity funds.

Curvey also serves a trustee for one of the owners of Impresa Management LLC, the manager of the F-Prime Capital’s venture investments. It’s not clear exactly who Curvey represents in that role; the stake is held in a trust, whose owners are not disclosed. But other filings indicate that Impresa is owned by the trusts of Johnson family members and Fidelity insiders.

Curvey’s history with the Johnsons’ private investing entities dates back more than two decades. In 1996, along with Abigail and Ned Johnson, Curvey sought and received an SEC exemption in 1996 that gave Impresa more latitude to invest on behalf of high-ranking Fidelity employees, SEC records show.

Partnership distributions to Curvey from venture investing have made him a lot of money. Curvey, for example, made millions of dollars from the venture capital arm’s investment in Britain’s COLT Telecom. In 2000, he donated some of those gains, nearly $3 million, to his family’s charitable foundation, according to an annual filing with the IRS.

Curvey and Wondrack declined to comment for this report. Fidelity declined to comment on the potential conflict of interest in their dual oversight roles.

THE YEAR’S BEST-PERFORMING IPO

Shareholders in the regular Fidelity mutual funds include millions of investors saving for retirement as well as employee 401(k) plans at top corporations such as Facebook, IBM and Oracle.

Those mom-and-pop investors missed out on 2015’s best-performing IPO. Fidelity funds stayed on the sidelines as shares of Aclaris Therapeutics skyrocketed after the drug maker listed its stock in October 2015.

F-Prime invested $16.3 million in Aclaris before the IPO – a stake whose value soared to $83.2 million in the first three months after the public offering, U.S. regulatory filings show.

Even if Fidelity fund managers had wanted to buy Aclaris shares after the IPO, in the open market, F-Prime’s stake of nearly 20 percent stake may have prevented them from doing so because of Fidelity’s guidelines on investing in companies in which the venture arm has a “substantial” stake.

Aclaris was 2015’s top public debut, its shares appreciating 145 percent over the $11 IPO price, according to Renaissance Capital, an IPO research and management firm.

At the end of June, F-Prime still held nearly 2.8 million Aclaris shares, a 13 percent stake, worth $51.5 million, according to Fidelity’s latest quarterly holdings disclosure. Fidelity funds did not own any Aclaris shares.

Fidelity fund competitors had no restraints on investing in Aclaris. Franklin Templeton funds bought nearly 1.2 million shares in the company in the month of the IPO, Franklin disclosures show. The Fidelity competitors, including the Franklin Small Cap Growth Fund, saw their combined initial stake of $17.3 million more than double in less than two months.

The Johnson-led venture arm scored another big payday when Adaptimmune Therapeutics went public in May 2015. F-Prime’s $8 million pre-IPO investment in the bioscience company surged in value to more than $270 million in the weeks after the IPO, Fidelity disclosures show.

Investors in the American Funds SmallCap World Fund, a Fidelity competitor, capitalized, too. The SmallCap World Fund made a similar-sized pre-IPO investment and saw a similar return, American disclosures show.

The Fidelity Select Biotechnology Portfolio bought about 1.5 million Adaptimmune shares the month after the IPO. But the biotech fund paid at least 24 times more for its shares than rivals did, Fidelity Select disclosures show.

As pre-IPO investors, F-Prime and the rival SmallCap World Fund got their Adaptimmune common stock, on a converted basis, for about 59 cents each, disclosures show.

The exact amount paid by the Fidelity biotech fund was not disclosed. But it was at least $14 a share, which was the low point for Adaptimmune shares the month of the IPO.

Adaptimmune traded recently at nearly $7 a share, which represents a big loss for the mass-market Fidelity biotech fund but a rich gain for the Johnsons’ F-Prime.

PILING IN

In the six cases Reuters examined where Fidelity bought into investments that were already held by F-Prime, Fidelity funds became the largest or one of the largest shareholders.

In general, newly minted public companies need long-term shareholders such as mutual funds in order to ride out the ups and the downs of the stock market, especially right after a public debut, said Bob Ackerman, founder and managing director of Allegis Capital, a venture firm based in San Francisco.

An investment by Fidelity – the third-largest mutual fund firm in the United States – is a boost for any new public company. A big fund’s investment broadens the shareholder base and makes it easier for venture capital investors to exit their investment at a profit.

“It’s a validation of the company and the exit strategy, especially if it’s a huge amount,” said Hans Tung, managing partner at GGV Capital. “It’s a good validation that a company has a lot of long-term growth potential ahead.”

Fidelity said there has never been a situation where F-Prime has directed a Fidelity mutual fund to make an investment in one of F-Prime’s portfolio companies.

Corporate governance and securities law specialists say that big Fidelity investments in companies owned by F-Prime could be interpreted as propping up the family’s interests and helping F-Prime’s exit strategy.

“It does raise a potentially serious question,” said James Post, a professor emeritus of markets, public policy and law at Boston University. “The uniqueness of the Fidelity arrangement requires the highest level of integrity.”

–

METHODOLOGY: How we analyzed the Johnsons’ trading

Reuters combed through public securities filings to explore overlap between the investing activities of Fidelity Investments, which serves some 20 million clients, and proprietary investment vehicles of the family that controls Fidelity, the Johnsons. Reuters identified 10 investments in which F-Prime Capital Partners, controlled by the Johnsons, was competing on the same turf as Fidelity mutual funds. The examination covered a three-year period, from 2013 to the present. During this time, Fidelity mutual funds began ramping up their strategy of investing in pre-IPO start-up companies. It is possible that the examination missed other relevant examples among F-Prime Capital’s many investments.

–

Additional reporting by Heather Somerville. Links added by Beachwood.

One of the best kept secrets in the mutual fund industry is the compensation of portfolio managers who oversee trillions of dollars in retirement assets. The SEC does not require any detailed disclosure.

But for those fund managers who make it to the top of Fidelity Investments, the payouts can rival and even surpass the typical pay of a CEO at an S&P 500 company, according to four people familiar with Fidelity’s payout structure. Median CEO Pay at S&P 500 companies totaled $10.8 million in 2015, according to pay research firm Equilar Inc.

Most of portfolio manager pay is determined by how well their funds perform against benchmarks like the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index. They also get awards of shares in FMR LLC – Fidelity’s closely-held parent company, which is controlled by the Johnson family. The value of FMR’s privately held stock rises and falls largely based on the performance of the mutual fund business.

Fidelity’s elite, including top portfolio managers, get an additional sweetener: lucrative distributions from investments made by a proprietary venture fund called F-Prime Capital Partners. The fund is run on behalf of the family of Fidelity Chief Executive Abigail Johnson and other company insiders.

In some cases, F-Prime’s best performing investments – such as Chinese web giant Alibaba – can add millions of dollars to their compensation, according to four people familiar with Fidelity’s compensation structure.

Fidelity is not required to disclose any detailed lists of who receives F-Prime distributions. The company declined to tell Reuters how many people were entitled to the biggest payouts from F-Prime.

But Reuters found that Will Danoff, who has run Fidelity’s flagship Contrafund for 25 years and currently oversees $100 billion-plus in assets as a solo portfolio manager, has received millions from F-Prime investments.

Will Danoff/Anthony Bolante, Reuters

Will Danoff/Anthony Bolante, ReutersAfter Alibaba’s 2014 IPO, F-Prime, an early investor, distributed shares in the Chinese company to investors. Danoff was among the group, according to two people familiar with the distribution.

Danoff received 46,154 Alibaba shares that cost $3,432, or 7 cents apiece, according to an annual report filed by his family’s private charitable foundation. The cheap stock reflects how F-Prime made an investment in Alibaba about 15 years before the company went public.

Danoff’s Alibaba shares were worth about $4 million when he received them. Alibaba went public at $68 a share in the largest IPO in history.

In May 2015, he donated the Alibaba stock as part of a $5 million gift to his alma mater, Harvard University, according to disclosures by Danoff’s family foundation.

While there’s no detailed disclosure about Danoff’s Fidelity compensation, the amount of assets in his family’s charitable foundation has surged to about $70 million in recent years, according to filings with the U.S. Internal Revenue Service. In 2015, Danoff contributed $31.1 million to the charity, including $12 million in Contrafund shares that he personally owned.

Danoff declined to comment.

F-Prime’s investments are managed by a closely held advisory firm, Impresa Management. Fidelity said the role of F-Prime and Impresa in the pay of its portfolio managers does not influence their stock picks for the mutual funds they run.

“It is simply not plausible that portfolio managers would invest on behalf of their funds in a way that would negatively impact the performance of the fund in order to boost the value of an Impresa investment,” Fidelity said in a statement. “Our compensation model for portfolio managers aligns their interests with the interests of the funds and other client accounts they manage, and we believe that relevant conflicts of interest relating to (portfolio manager) compensation have been disclosed in the funds’ SEC filings required by the rules.”

–

Comments welcome.

Posted on October 13, 2016