By Mark Newman

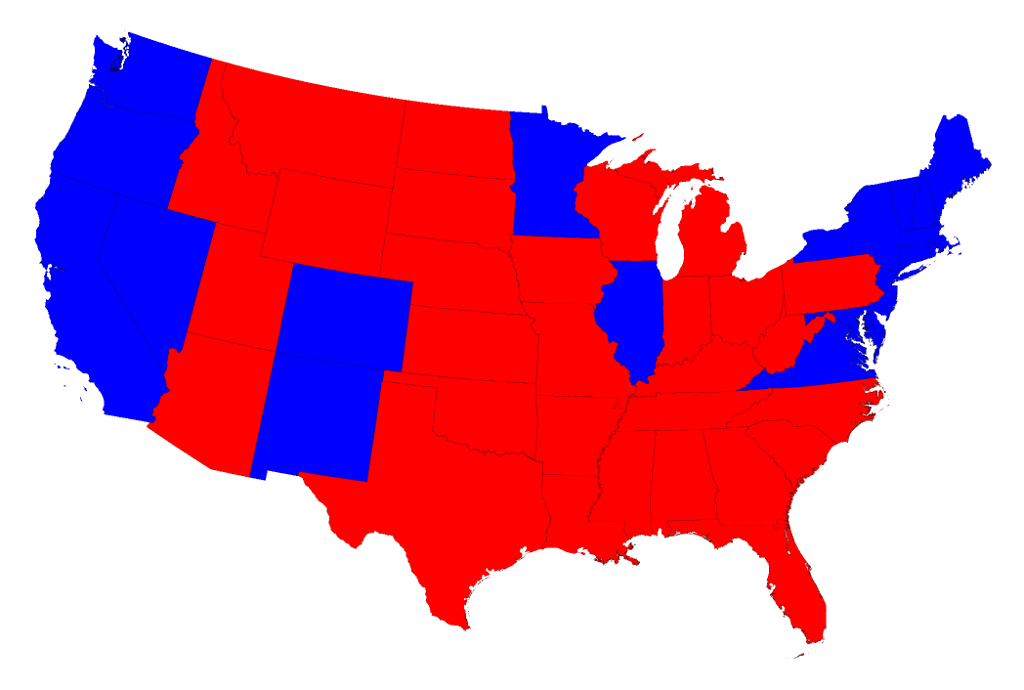

Most of us are, by now, familiar with the maps the TV channels and websites use to show the results of presidential elections. Here is a typical map of the results of the 2016 election:

The states are colored red or blue to indicate whether a majority of their voters voted for the Republican candidate, Donald Trump, or the Democratic candidate, Hillary Clinton, respectively. There is significantly more red on this map than there is blue, but that is in some ways misleading: the election was much closer than you might think from the balance of colors, and in fact Clinton won slightly more votes than Trump overall. [Editor’s Note: By the time all the ballots are counted, Clinton’s winning margin in the popular vote is expected to grow to about 2 million.]

The explanation for this apparent paradox, as pointed out by many people, is that the map fails to take account of the population distribution. It fails to allow for the fact that the population of the red states is on average significantly lower than that of the blue ones. The blue may be small in area, but they represent a large number of voters, which is what matters in an election.

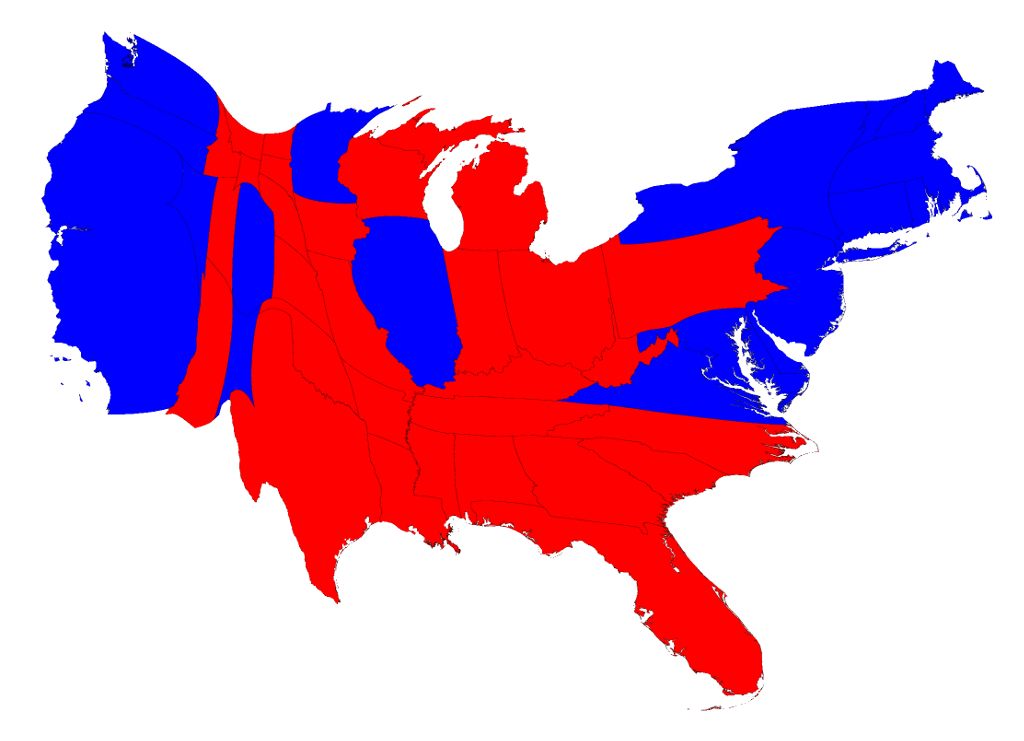

We can correct for this by making use of a cartogram, a map in which the sizes of states are rescaled according to their population. That is, states are drawn with size proportional not to their acreage but to the number of their inhabitants, states with more people appearing larger than states with fewer, regardless of their actual area on the ground. On such a map, for example, the state of Rhode Island, with its 1.1 million inhabitants, would appear about twice the size of Wyoming, which has half a million, even though Wyoming has 60 times the acreage of Rhode Island.

Here are the 2016 presidential election results on a population cartogram of this type:

As you can see, the states have been stretched and squashed, some of them substantially, to give them the appropriate sizes, though it’s done in such a way as to preserve the general appearance of the map, so far as that’s possible. On this map the total areas of red and blue are more similar, although there is still more red than blue overall.

The presidential election, however, is not actually decided on the basis of the number of people who vote for each candidate but on the basis of the Electoral College. Under the U.S. electoral system, each state in the union contributes a certain number of electors to the Electoral College, who vote according to the majority in their state. (Exceptions are the states of Maine and Nebraska, which use a different formula that allows them to split their electoral votes between candidates.) The candidate receiving a majority of the votes in the Electoral College wins the election. The electors are apportioned among the states roughly according to population, as measured by the census, but with a small but deliberate bias in favor of less populous states.

We can represent the effects of the Electoral College by scaling the sizes of states to be proportional to their number of electoral votes, which gives a map that looks like this:

This cartogram looks similar to the previous one, but it’s not identical. Wyoming, for instance, has approximately doubled in size, precisely because of the bias in favor of states with smaller populations.

The areas of red and blue on the cartogram are now proportional to the actual numbers of electoral votes won by each candidate. Thus this map shows at a glance both which states went to which candidate and which candidate won more Electoral College votes. There is more red than blue in this case, indicating that Donald Trump won the election – something you cannot easily tell from the normal election-night red and blue map.

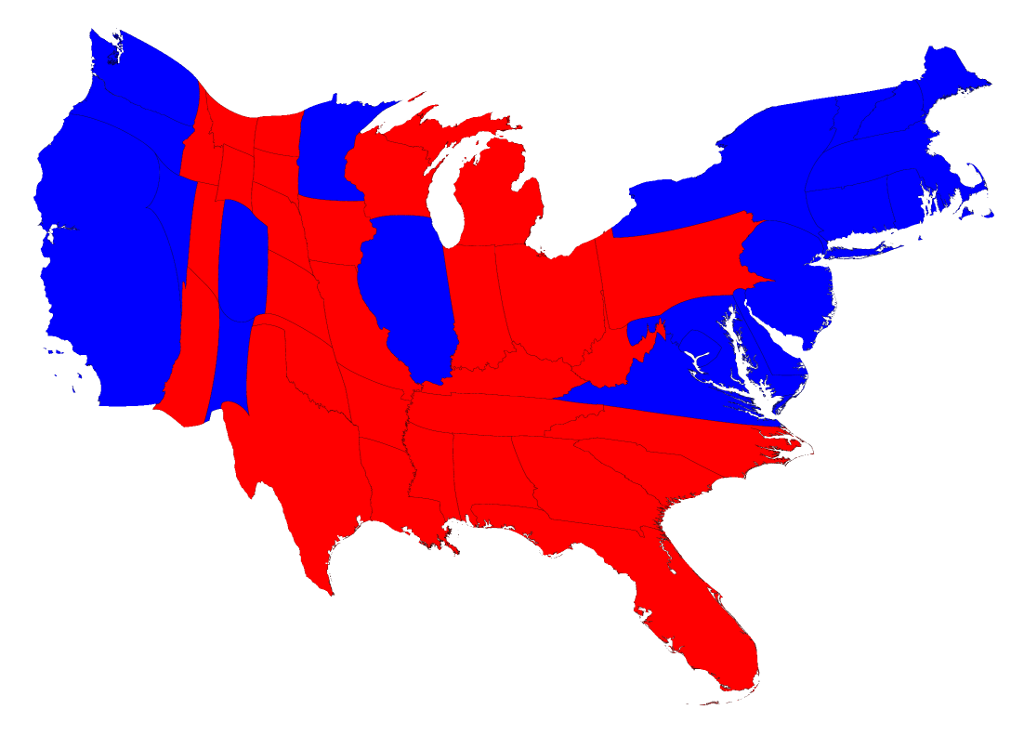

Election Results By County

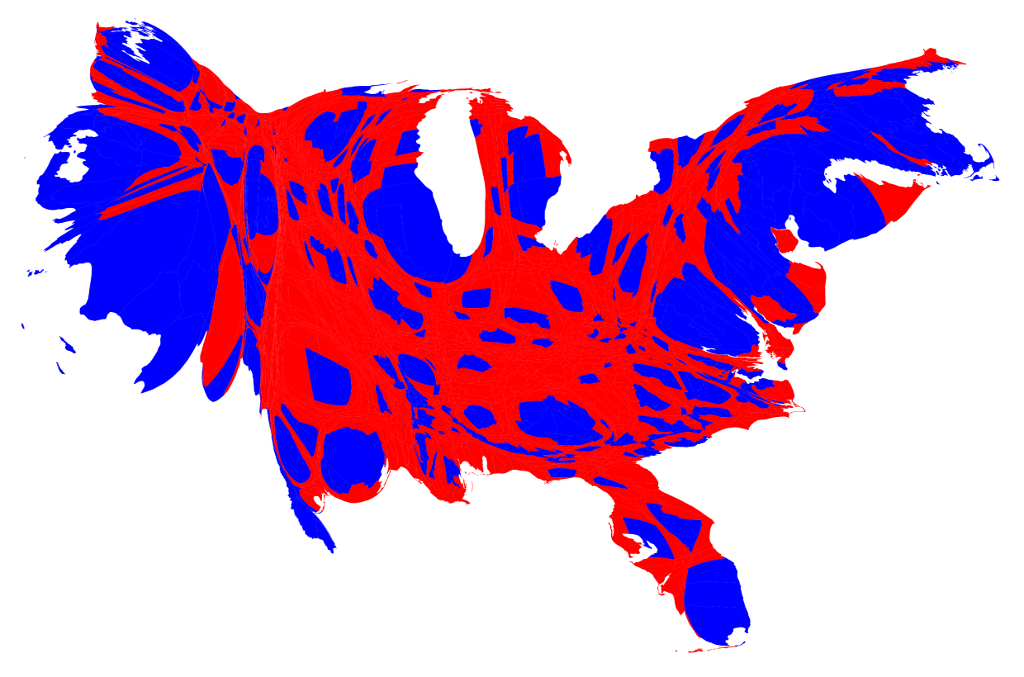

We can go further. We can do the same thing also with the county-level election results and the images are even more striking. Here is a map of U.S. counties, again colored red and blue to indicate Republican and Democratic majorities respectively:

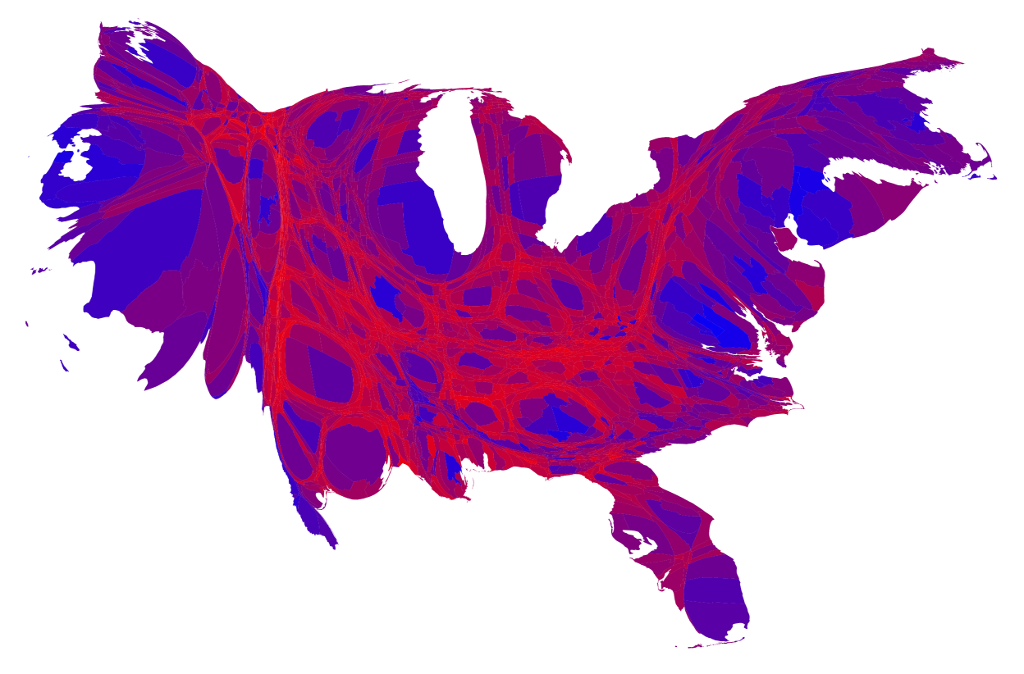

Now the effects we saw at the state level are even more pronounced: the red areas appear overwhelmingly in the majority, despite the closeness of the vote. Again, we can make a more helpful representation by using a cartogram. Here is what the cartogram looks like for the county-level election returns:

However, this map is still somewhat misleading because we have colored every county either red or blue, as if every voter voted the same way. This is, of course, not realistic: all counties contain both Republican and Democratic supporters, and in using just the two colors on our map we lose any information about the balance between them. There is no way to tell whether a particular county went strongly for one candidate or the other or whether it was relatively evenly split.

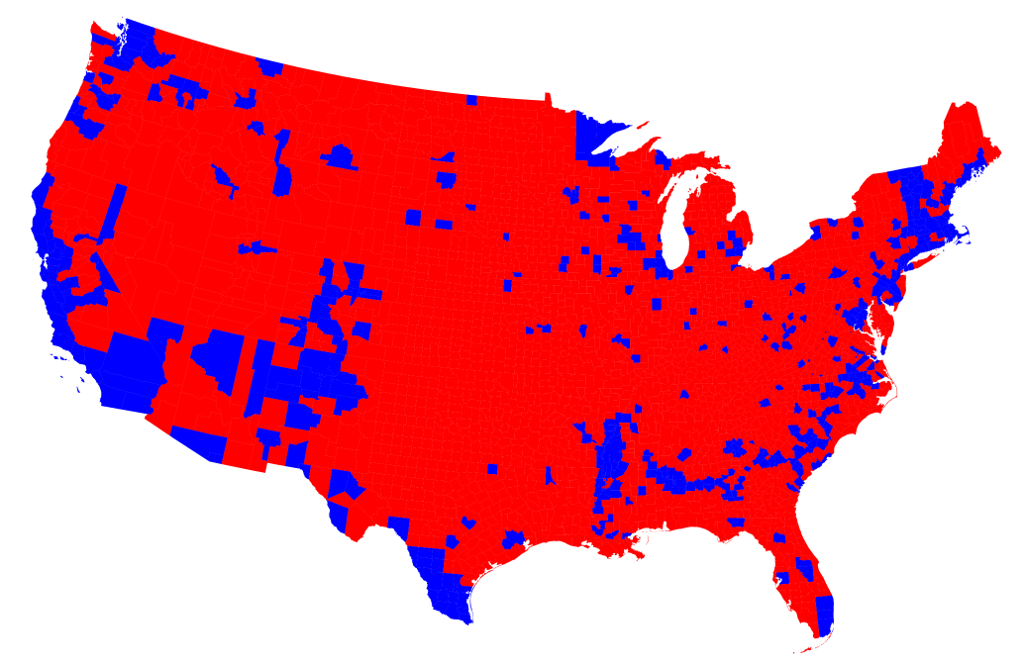

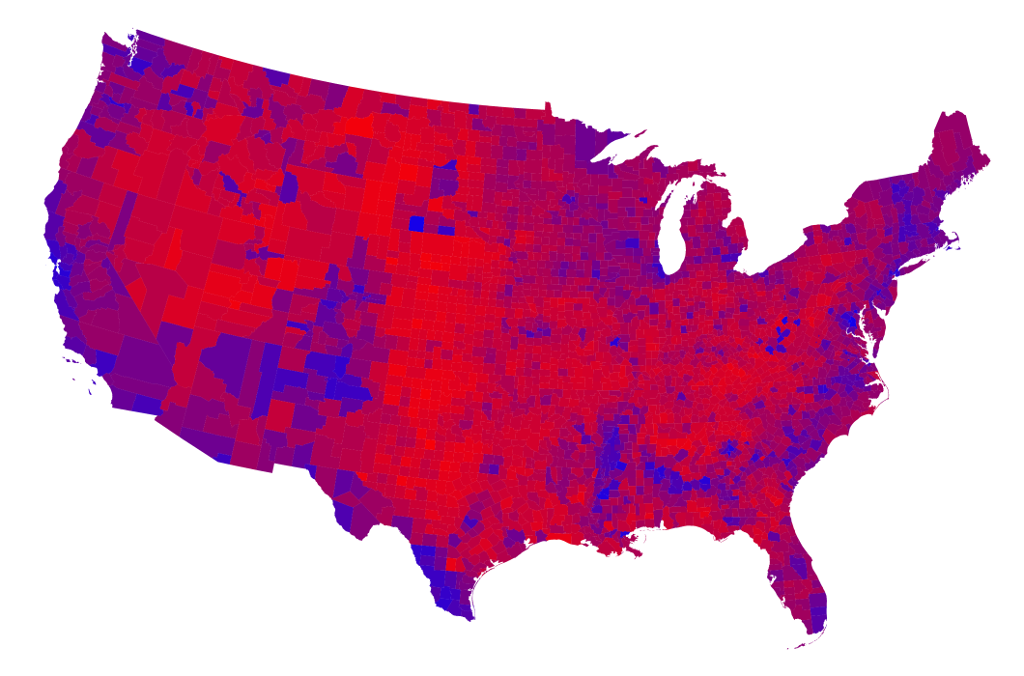

One way to reveal more nuance in the vote is to use not just two colors, red and blue, but to use red, blue, and shades of purple in between to indicate percentages of votes. Here is what the normal map looks like if you do this:

And here’s what the cartogram looks like:

As this map makes clear, large portions of the country are quite evenly divided, appearing in various shades of purple, although a number of strongly Democratic or Republican areas are visible too.

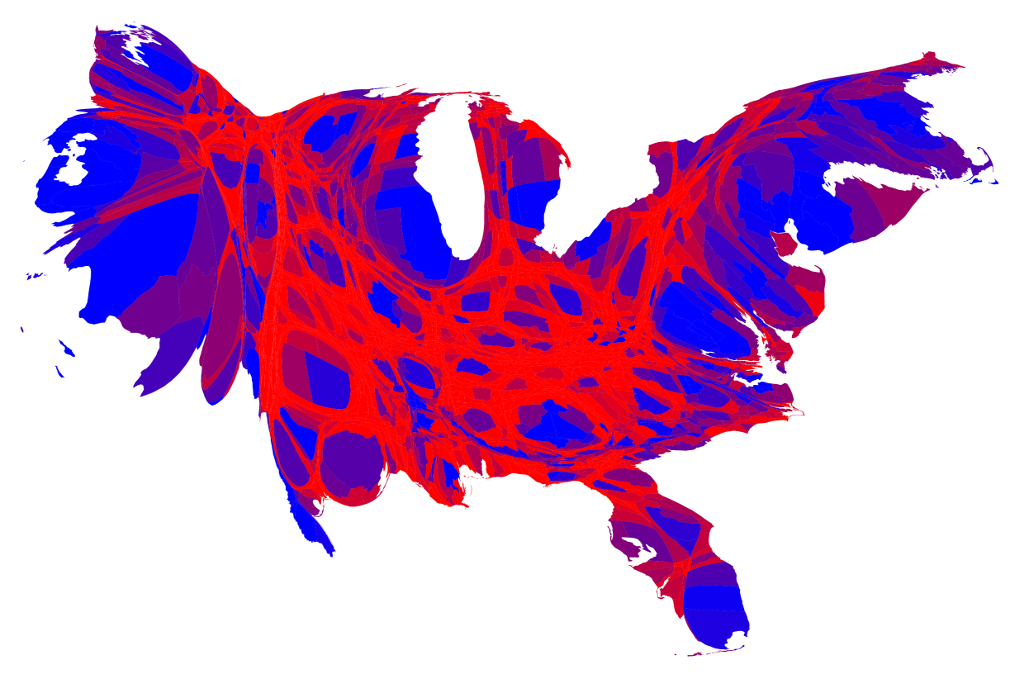

A slight variation on the same idea is to use a nonlinear color scale like this:

These maps use a color scale that ranges from red for 70% Republican or more, to blue for 70% Democrat or more. This is sort of practical, since there aren’t many counties outside that range anyway, but to some extent it also obscures the true balance of red and blue.

–

Notes:

Frequently asked questions (FAQs): A list of frequently asked questions concerning these maps, along with answers, can be found here.

Election results: The maps were made using the election results as of November 10, 2016. A small number of precincts still had not reported by that date, so results in a few counties can be expected to change a little.

Thanks: The idea of using a purple map was suggested by Professor Robert Vanderbei, who has made a terrific series of maps of his own, which you can find here.

Software: My computer software for producing cartograms is freely available here.

© 2016 M. E. J. Newman

![]()

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License. Text and images may be freely distributed. I’d appreciate hearing from you if you make use of them.

The views expressed are personal and are not necessarily shared by the University of Michigan.

Mark Newman, Department of Physics and Center for the Study of Complex Systems, University of Michigan

E-mail: mejn@umich.edu

Updated: November 10, 2016

–

Comments welcome.

Posted on November 12, 2016