By E.K. Mam

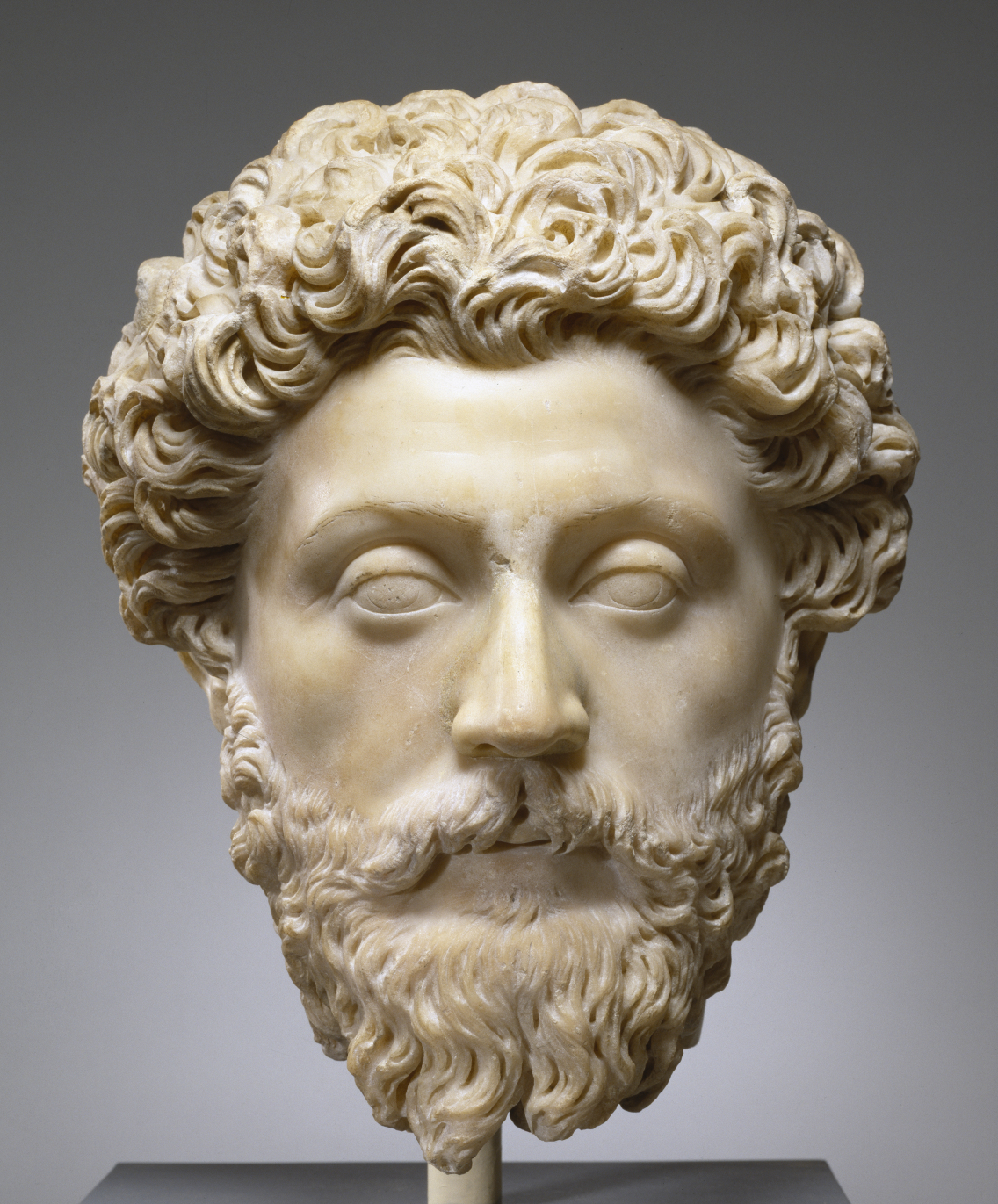

“If you are distressed by anything external, the pain is not due to the thing itself, but to your estimate of it; and this you have the power to revoke at any moment.” – Marcus Aurelius

With some chagrin, I have to admit that I was one of those students in history class who always jumped in to correct the teacher; challenge the teacher; thought I was more qualified than the teacher.

Maybe it was my zeal for history that made me such a pain in the ass, though it’s important to know that doesn’t mean I romanticize the past like some history buffs. I’m able to see quite clearly that being born today is far better than to have been born in another era. No, things aren’t perfect today. Yes, it’s possible that some things were done better in the past. But with improved plumbing, the refinement of democracy, open-heart surgery, and Starbucks, there isn’t much competition between today and yesterday.

Remarkably, however, the thread that binds the pages of our past and present into history books is uncannily identical. Despite the stark differences between yesteryear and the contemporary world, I’ve learned that history in its meat and bones is uniform from country to country, decade to decade.

I’m not a historian, but I feel qualified enough to assert that the history of human affairs is consistently filled with misery and strife. Very few people have known a good life. The day to day of nearly everyone who has lived has been filled with back-breaking labor; disease and its inconvenient friend, the Grim Reaper, came rapping on the door so often some no longer bothered keeping it shut; personal development, which today consists of a gym membership and self-help books, used to be considered just not dying another day. Suffering was so common that it was practically considered a synonym for “living.”

I can only imagine I speak for the majority of history enthusiasts when I say the World Wars are my favorite events to study. In such a short period of time (four years for the First World War and six for the Second) there was an incomprehensible amount of suffering. And this suffering was made all the more real and unbearable for a number of reasons. It really wasn’t all that long ago, if you think about it. Only a few days ago VE Day was being celebrated. Technology was advanced enough to document the anguish, which brought light to the horrors that couldn’t be articulated. Technology was also advanced enough to come up with new weapons. Mustard gas, shot guns, machine guns, and tanks (just to name a few) must have appeared like physical manifestations of hell to the soldiers who came face to face with these instruments of death. How can I continue to study these events, given how disturbing the first-hand accounts are? How can I flip open textbooks to look at the photographs taken, given how stomach-turning the maimed limbs and faces twisted in pain are?

Mr. Aurelius/Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

Mr. Aurelius/Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

For the suffering is my primary fascination. The conditions for the soldiers were unimaginable. The anxiety of the civilians must have been unbearable, never knowing what to expect. And yet, life went on. Amidst all the hell, civilians did their best to establish a normalcy. Shops continued to run. Houses needed cleaning. Clothes needed sewing. People even found the strength to help one another, and to smile and tell jokes. The soldiers, of course, had it far worse. Yet they, too, managed to fight on, to live another day. I’m truly baffled by the strength of the people who – when faced with such inhumane, hellish conditions – marched on, dared to show their face the next day, held fast to whatever it was that kept them alive.

The people of today, at least those born in First World countries, are not without pains of their own. But a majority of us are so familiar with comfort and ease that we’ve forgotten what a privileged position we’re in. We have the latest devices that connect us with the world. We have food in our refrigerators. We have clothes on our backs. We have laws on our side. We have opportunities galore. Life is difficult, of course . . . but we’re just fine if you think about it.

It’s inaccurate to say the youth of today don’t know what suffering is. Suffering is diverse; it comes in many different forms. My fellow Generation Z-ers are faced with the doom and gloom of unstable economies; problematic governments; withering personal relationships; shaky morals and societies; and now a pandemic. But we’re still in a better position than our forebears. Despite all that we have against us, we are not 9 feet under in a muddy trench in a different country only a few meters away from a blood-thirsty enemy. Life is no picnic . . . it never has been. But I’ll take the woes of today over the woes of yesterday any day of the week.

Stoicism is a philosophy that emphasizes self-mastery, discipline, and control by learning how to accept the negatives of life gracefully. Before I started studying history in my free time, my reaction to pains and hardships would be: “Poor me! How can this happen to me? I’m all alone! No one can understand what I’m going through!” But after reading about boys my age – or younger – enlisting to go and fight in a war; houses being blasted to rumble; the enemy invading and occupying; and women being raped by their “liberators,” I began to realize that my life and whatever challenges I have dealt with really haven’t been so bad. I started having these epiphanies just as I stumbled across stoicism, and I made the connection between the two that changed my life.

History showed me that to live is to suffer, but stoicism taught me that trying to run away from the inevitable was useless. Instead, I ought to buckle down, brace for impact, and remember it could always be worse. Keep calm and carry on? Maybe back then. Now? Post about your out-of-perspective hardships on Tumblr with a “doomsday-esque meets damsel in distress” tone instead of tackling the problem head-on with discretion and resilience and a degree of privacy. I don’t believe in sharing every woe and foe on social media; I don’t believe in juvenile and theatrical outbursts when you’re an adult; I don’t believe in thinking the world is terribly mean and unjust to you and only you. Quite regretfully for everyone, the world is cold and unkind. To some more than others, true; however, no one leaves this life scarless. I wonder what sort of a world we’d live in if more people thought this way, too.

E.K. Mam is a Communication student at UIC.

–

Comments welcome.

Posted on June 12, 2020