By Lindsay Grace/The Conversation

Video games are often blamed for unemployment, violence and addiction – including by partisan politicians raising moral concerns. It might feel like something new, a sidecar to technology. But fears about the effects of recreational games on society as a whole are centuries old. History shows a cycle of apprehension and acceptance about games that is very like events of modern times.

One of the earliest known written descriptions of games, for example, comes from the Dialogues of the Buddha, which dates back to the fifth century B.C. and purports to record the actual words of the Buddha himself. In them, he is reported to say that “some recluses . . . while living on food provided by the faithful, continue addicted to games and recreations; that is to say . . . games on boards with eight or with 10, rows of squares.”

That reference is widely recognized as describing a predecessor to chess – a much-studied game with an abundant literature in cognitive science and psychology.

In fact, chess has been called an art form and even used as a peaceful U.S.-Soviet competition during the Cold War.

Despite the Buddha’s concern, chess has not historically raised concerns about addiction. Scholars’ attention to chess is focused on mastery and the wonders of the mind, not the potential of being addicted to playing.

Somewhere between the early Buddhist times and today, worries about game addiction have given way to scientific understanding of the cognitive, social and emotional benefits of play – rather than its detriments – and even viewing chess and other games as teaching tools for improving players’ thinking, social-emotional development and math skills.

Games And Politics

Dice, an ancient invention developed in many early cultures, found their way to ancient Greek and Roman culture. It helped that both societies had believers in numerology, an almost religious link between the divine and numbers.

So common were games of dice in Roman culture that Roman emperors wrote about their exploits in dice games such as Alea. These gambling games were ultimately outlawed during the rise of Christianity in Roman civilization because they allegedly promoted immoral tendencies.

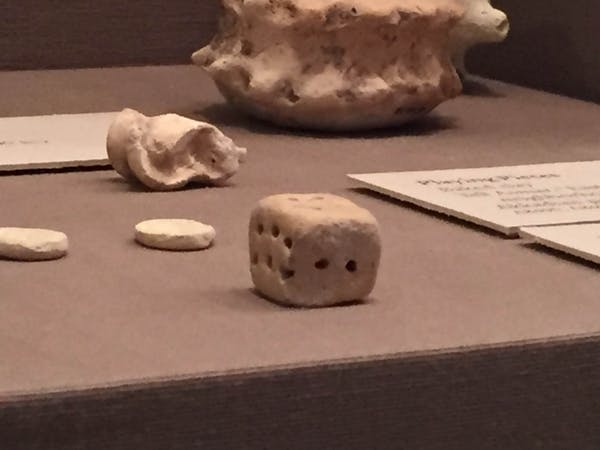

A die among other playing pieces from the Akkadian Empire, 2350-2150 B.C., found at Khafajah in modern-day Iraq/CC BY-SA

A die among other playing pieces from the Akkadian Empire, 2350-2150 B.C., found at Khafajah in modern-day Iraq/CC BY-SA

More often than not, the concerns about games were used as a political tool to manipulate public sentiment. As one legal historian puts it, statutes on dice games in ancient Rome were only “sporadically and selectively enforced . , , what we would call ‘sports betting’ was exempted.” The rolling of dice was prohibited because it was gambling, but wagering on the outcomes of sport were not. Until, of course, sports themselves came under fire.

The history of the Book of Sports, a 17th-century compendium of declarations of King James I of England, demonstrates the next phase of fears about games. The royal directives outlined what sports and leisure activities were appropriate to engage in after Sunday religious services.

In the early 1600s, the book became the subject of a religious tug of war between Catholic and Puritan ideals. Puritans complained that the Church of England needed to be purged of more influences from Roman Catholicism – and liked neither the idea of play on Sundays nor how much people liked doing it.

In the end, English Puritans had the book burned. As Sports Illustrated put it in 1962, “Sport grew up through Puritanism like flowers in a macadam prison yard.”

Pinball In The 20th Century

In the middle part of the 20th century, one particular type of game emerged as a frequent target of politician concern – playing it was even outlawed in cities across the country. That game was pinball. The parallels with today’s concerns about video games are clear.

In her history of moral panics about elements of popular culture, historian Karen Sternheimer observed that the invention of the coin-operated pinball game coincided with “a time when young people – and unemployed adults – had a growing amount of leisure time on their hands.”

As a result, she wrote, “it didn’t take long for pinball to show up on moral crusaders’ radar; just five years spanned between the invention of the first coin-operated machines in 1931 to their ban in Washington, D.C., in 1936.”

New York City mayor Fiorello LaGuardia argued that pinball machines were “from the devil” and brought moral corruption to young people. He famously used a sledgehammer to destroy pinball machines confiscated during the city’s 34-year ban, lodged by the Guinness Book of World Records as the longest in gaming history.

His complaints sound very similar to modern-day concerns that video games contribute to unemployment at a time when millennials are one of the most underemployed generations.

Even the cost of penny arcade pinball machines raised political alarms about wasting children’s money, in much the way that politicians declare they have problems with small purchases and electronic treasure boxes in video games.

As far back as the Buddha’s own teachings, moral leaders were warning about addicting games and recreations, including “throwing dice,” “Games with balls” and even “turning somersaults,” recommending the pious hold themselves “aloof from such games and recreations.”

Then, as now, play was caught in society-wide discussions that really had nothing to do with gaming – and everything to do with keeping or creating a purported established moral order.

Lindsay Grace is the Knight Chair of Interactive Media at the University of Miami. This post is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

–

Comments welcome.

Posted on October 10, 2019