By The Beachwood Nanostories Affairs Desk

“You might have seen Bill Wasik’s byline in Harper’s, where he’s a senior editor,” M.J. Fine writes in the Philadelphia City Paper. “Or maybe you don’t recognize his name but remember one of his Web projects: a satirical one-off called The Right-Wing New York Times, the short-lived buzzkill blog Stop Peter Bjorn and John, or the political-smear repository OppoDepo. But, as his publisher has realized, Wasik’s most notable as the guy behind 2003’s flash-mob craze.

“In And Then There’s This: How Stories Live and Die in Viral Culture, Wasik connects the dots between the overstimulation that we perceive as boredom and our Internet-driven culture’s short attention span. He covers multitasking and memes, compulsive clicking and corporate co-optation of viral ads, and the sped-up news cycle that turns nonentities into microcelebrities and nanostories. (How’s Jon and Kate Gosselin’s marriage today?) And he makes keen points about what our tastemakers’ relentless appetite for the next big thing means for artists and creators as their efforts are disseminated out of context and with more emphasis on novelty than on talent or importance. Witness the backlash that starts almost as soon as a band’s been discovered. (Of one indie-rock group’s debut album, Wasik quotes a DJ saying, ‘This is a great movie – I hope there’s not a sequel.’)”

–

Well put. And with that we bring you an excerpt from And Then There’s This, reprinted by arrangement with Viking, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. Copyright Bill Wasik.

–

I begin with a plea to the future historians, those eminent and tenured minds of a generation as yet unconceived, who will sift through our benighted present, compiling its wreckage into wiki-books while lounging about in silvery bodysuits: to these learned men and women I ask only that in telling the story of this waning decade, the first of the twenty-first century, they will spare a thought for the fate of a girl named Blair Hornstine.

Period photographs will record that Hornstine, as a high-school senior in the spring of 2003, was a small-framed girl with a full face, a sweep of dark, curly hair, and a broad, laconic smile. She was an outstanding student – the top of her high-school class in

Moorestown, New Jersey, in fact, boasting a grade-point average of 4.689 – and was slated to attend Harvard. But as her graduation neared, the district superintendent ruled that the second-place finisher, a boy whose almost-equal average (4.634) was lower due only to a technicality, should be allowed to share the valedictory honors.

At this point, the young Hornstine made a decision that even our future historians, no doubt more impervious than we to notions of the timeless or tragic, must rate almost as Sophoclean in the fatality of its folly. After learning of the superintendent’s intention, Hornstine filed suit in U.S. federal court, demanding that she not only be named the sole valedictorian but also awarded punitive damages of $2.7 million. Incredibly, a U.S. district judge ruled in Hornstine’s favor, giving her the top spot by fiat (though damages were later whittled down to only sixty grand). Meanwhile, however, a local paper for which she had written discovered that she was a serial plagiarist, having stolen sentences wholesale from such inadvisable marks as a think-tank report on arms control and a public address by President Bill Clinton. Harvard quickly rescinded its acceptance of Hornstine, who thereafter slunk away to a fate unknown.I stoop to shovel up the remains of Blair Hornstine’s reputation not to draw any moral from her misdeeds. Of the morals that might be drawn, roughly all were offered up at one point or another during the initial weeks after her lawsuit. She was “just another member of a hyper-accomplished generation for whom getting good grades and doing good deeds has become a way of life,” wrote the Los Angeles Times. The Philadelphia Daily News eschewed such sociology, instead citing more structural causes: “With college costs skyrocketing, scholarship dollars limited and competition fierce for admissions, the road to the Ivy League has become a bloody battleground.” MSNBC’s Joe Scarborough declared that “across the country, parents are suing when the ball doesn’t bounce their child’s way,” while CNN’s Jeffrey Toobin went somewhat more Freudian, branding her judge father as another example of “lawyers . . . inflicting it on [their] children.” Nonprofessional Internet pundits, meanwhile, were every bit as incisive. “The girl’s father is a judge,” wrote one proto-Toobin on MetaFilter, a popular community blog. “Guess he’s taught her too much about the legal system.”

Echoed another commenter: “Behind every over-achieving student here are usually a pair of over-achieving parents who want their child o live up to their ridiculous expectations.”

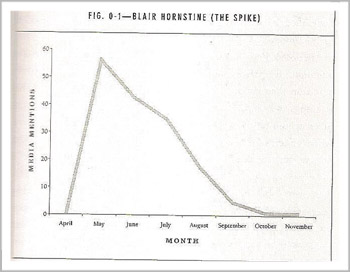

No, I offer up Blair Hornstine to history simply for the trajectory of her short-lived fame, the rapidity with which she was gobbled up into the mechanical maw of the national conversation, masticated thoroughly, and spat out:

This telltale spike, this ascent to sudden heights followed by a decline nearly as precipitous – it is a pattern that will recur throughout this book, and it is one that even the casual consumer of mass media will surely recognize. To keep up with current affairs today is to suffer under a terrible bombardment of Blair Hornstines, these media pileons that surge and die off within a matter of months, days, even hours.

Consider just one of the weeks (May 25 through June 1) that Blair Hornstine was being dragged through the streets behind the media jeep; tied up beside her were a host of other persons or products or things, in various states of uptake or castoff – in the realm of politics, Pfc. Jessica Lynch (on her way down, as her rescue tale was found to have been exaggerated) and Howard Dean (on his way up in the race for president, having excited the Internet); in fashion, the trucker hat (on its way down) and Friendster.com (on its way up); in music, an indie-rock band called the Yeah Yeah Yeahs (down) and a new subgenre of “emo” called “screamo” (up); all these and more were experiencing their intense but ephemeral media moment during one week in the early summer of 2003.

We do not have an easy word to describe these transient bursts of attention, in part because we often categorize them differently based on their object. When this sort of fleeting attention attaches to things, we tend to call them “fads”; but this term, I think, conjures up too much the media-unsavvy consumer of an earlier era, while underestimating the extent to which our enthusiasms today are entirely knowing, postironic, aware. If there is one attribute of today’s consumers, whether of products or of media, that differentiates them from their forebears of even twenty years ago, it is this: they are so acutely aware of how media narratives themselves operate, and of how their own behavior fits into these narratives, that their awareness feeds back almost immediately into their consumption itself.

Likewise, when this sort of transient attention falls on people, we tend to describe it as someone’s “fifteen minutes of fame.” But is celebrity really what is at work here? The majority of the tens of millions of people who pondered the story of Blair Hornstine never knew what she looked like, or cared. What they knew, instead, was how she fit handily into one or more of the various meanings imposed on her: the ambition-addled generation, the lawsuit-drunk society. Most people who remember Blair Hornstine today will recall her not by name or face but simply by role – as “that girl,” perhaps, “who sued to become valedictorian.” No name need even be invoked for her to do her conversational work.

–

Commentary/Resources:

* “[I]n the book I use the example of Blair Hornstine, and you see a similar thing more recently with Susan Boyle, where people become instant celebrities,” Wasik says in this interview. “But what’s really at work there is the way they become not just celebrities but symbols. To a certain extent, you don’t actually have to be famous – your face doesn’t have to be seen – in order for you to perform this function in the churning media conversation.”

* “Poised somewhere between meta-gonzo reporting and Malcolm Gladwell-esque pop psychology, And Then There’s This charts how ‘nanostories’ reflect today’s competitive, often consumer-driven media and just how easily they can be manipulated,” David Fears writes at Time Out Chicago.

“Though Wasik’s no stranger to first-person tomfoolery in the name of the Fourth Estate, his entertaining journey through the world of snarky blogs and DIY hipster tastemakers occasionally suffers from one too many servings of ‘gotcha!’ gimmickry. Yet his thesis about the supernova rapidity of news cycles certainly has merit; you could easily see the book becoming a momentary sensation before the next big nonfiction thing arrives.”

* BillWasik.com

* Nieman Journalism Lab video

Posted on July 24, 2009