By Sarah Witman/Undark

The way most unnatural deaths are investigated in the U.S. is not as flawless or fast-paced as shows like CSI: Crime Scene Investigation and Law and Order: Special Victims Unit would have you believe. But in the early 20th century, it was much worse.

In 1914, New York City’s commissioner of accounts, Leonard Wallstein, investigated the city’s coroner system and found it to be grossly inefficient and corrupt. Of the 65 coroners holding office at the time, “not one was thoroughly qualified by training or experience for the adequate performance of his duties,” he wrote in his report. The few who had medical degrees were “drawn from the ranks of mediocrity,” motivated only by the money they could extort from police, prosecutors, or the accused.

By the 1920s, two cities – Boston and New York City – had converted from the coroner system to the medical examiner system. Unlike coroners, medical examiners were required to have some kind of post-secondary education, as well as specialized training in forensic pathology – learning to decipher clues like ligature marks, decomposition, and lividity to determine the time, manner, and cause of death.

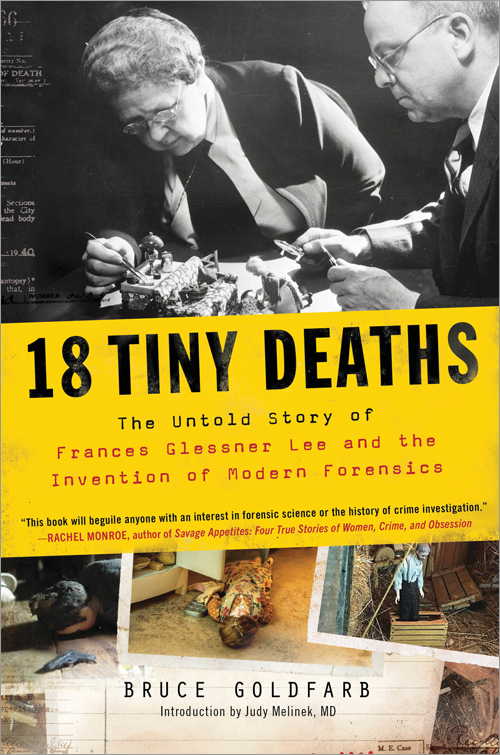

In 18 Tiny Deaths: The Untold Story of Frances Glessner Lee and the Invention of Modern Forensics, Bruce Goldfarb vividly recounts one woman’s quest to expand the medical examiner system and advance the field of forensic pathology.

Lee is perhaps best known for creating the “Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death,” dioramas of crime scenes in miniature – macabre dollhouses – depicting victims of arson, stabbing, hanging, carbon monoxide poisoning, and more. She handcrafted most of the furniture, clothing, and other minutiae herself to get each detail just right, accurately illustrating traces of physical evidence left at real crime scenes. Stored today at the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner in Baltimore, the Nutshell Studies are still dusted off once a year and used as training tools for the Frances Glessner Lee Seminar in Homicide Investigation. However, as Goldfarb points out, Lee didn’t make the Nutshell Studies until she was in her 60s, toward the latter half of World War II.

Before that, she had spent decades advocating for the medical examiner system – now practiced in 22 states, plus Washington, D.C. – and developing an educational framework for forensic pathology. In 1931, she founded the first academic department in forensic science – the Department of Legal Medicine at Harvard University. After years of training police officers how to find and preserve evidence at crime scenes, she was hired as captain of the New Hampshire State Police in 1943, making her the nation’s first female police captain. In the introduction of 18 Tiny Deaths, forensic pathologist Judy Melinek dubs her “the matriarch of the modern practice of forensic pathology.”

Lee was born in 1878 and grew up in Gilded Age Chicago, the daughter of one of the wealthiest men in the city. Her father was a partner in the International Harvester Company, which made farming equipment. In addition to a generous gift of $125,000 in company stock from her father when she was 25, Lee later inherited an even larger sum from her uncle, a childless millionaire.

Frances Glessner Lee as a teenager/Glessner House Museum

Frances Glessner Lee as a teenager/Glessner House Museum

Despite a lifelong interest in medicine, she never went to medical school, or even college. She married young, had three children, divorced her husband (Blewett Lee, the son of a Confederate lieutenant general), and never remarried. It wasn’t until she was 51 and living in Boston that she began her career in forensic science.

While hospitalized with an unexplained illness at Phillips House, an eight-story mansion housing wealthy inpatients in Boston’s Beacon Hill neighborhood, she crossed paths with George Burgess Magrath, a childhood friend who was recuperating there around the same time. Magrath was the city’s medical examiner – the second person to hold the position – and he had developed severe infections in his hands as the result of a failing liver (he had alcoholism) combined with exposure to formaldehyde in his work.

Goldfarb depicts Magrath as a Sherlockian figure, known throughout the city as much for his eccentricity as for his forensic expertise. Magrath captivated Lee with tales of his on-the-job exploits and impressed upon her the importance of the medical examiner system. “Every person, he felt, was entitled to a thorough, scientific, and impartial death investigation, should it be necessary,” Goldfarb writes of Magrath. Rather than relying on surface-level evidence like bullet holes or stab wounds, Magrath employed his skill as a physician to detect barely perceptible signs of violence – from small spots caused by bleeding under the skin to the puncture mark of a hypodermic needle.

Lee’s friendship with Magrath instilled in her a fierce determination to share his body of knowledge more widely. With his guidance, at the age of 53, she launched the Department of Legal Medicine at Harvard. Lee’s personal wealth allowed her to shape the department, for the most part, as she saw fit. She and Magrath had offices on campus, and she paid his salary and pension (anonymously) until his death. In 1940, its first year of operation, the department uncovered evidence of four homicides – previously ruled as accidents, suicides, or natural deaths – that would have gone undetected, and exonerated suspects in nine cases that would have otherwise been prosecuted as homicides.

Lee sent the department’s first chairman on a two-year trip around the world to study forensic techniques in Denmark, Egypt, England, France, Germany and other places where the field was more advanced. Her private collection of books, posters and other instructional materials, eventually absorbed into the medical school’s main library, contained more than 3,000 items. Despite her magnanimity, Lee faced institutional inertia at every turn – not to mention deep-seated prejudice. Even after she’d founded the department at Harvard, a Suffolk County medical examiner still saw Lee as merely “a wealthy grandmother with no formal education,” writes Goldfarb. But she always employed the same “diplomacy and tact” that had helped her navigate the world as a woman in a male-centric society her entire life.

Goldfarb’s background as a journalist and former EMT paramedic shines through in his telling of Lee’s life story. The book is loaded with jewel-bright details that bring each personality to life – from Magrath’s wild mane of hair (“like a lion resting”) to the type of flower (lily of the valley) that Lee carried down the aisle on her wedding day. Most arresting is the book’s central episode, in which Magrath performs an autopsy in front of Lee, soon after their release from Phillips House. Though gory, Goldfarb’s description is reflective of how the unlikely duo viewed the human body, internal organs and all: “breathtakingly beautiful.”

Goldfarb also currently works as a public information officer for Baltimore’s Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, giving him intimate access to the Nutshell Studies – on permanent loan from Harvard since 1967, as instructed by Lee’s heirs – and other important sources. He does an excellent job of distilling what must have been an overwhelming amount of material into a well-paced, highly readable narrative.

Goldfarb does have a tendency to name-drop minor historical figures without much explanation. Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. was a childhood friend, but it’s never mentioned that his father was the acclaimed landscape architect who designed Central Park and Prospect Park, as well as a garden for the Glessners’ vacation home in New Hampshire. Maud Howe Elliott (a notable writer) and her mother, Julia Ward Howe (who penned “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”), are similarly alluded to in passing.

And a couple of the book’s broader claims might also raise some eyebrows. For example, Goldfarb asserts that the Nutshell Studies “serve a purpose that cannot be duplicated by any other medium. Not even state-of-the-art virtual reality approaches the experience of viewing a three-dimensional setting.” That seems debatable given today’s high-tech tools – though it would undoubtedly be less charming. But such cases of hyperbole are thankfully rare.

Frances Glessner Lee working in her workshop at The Rocks/Glessner House Museum

Frances Glessner Lee working in her workshop at The Rocks/Glessner House Museum

As Goldfarb painstakingly makes clear, Lee’s dream of a nationwide medical examiner system – with fully trained and independently appointed medical examiners in every state, working in tandem with the police and legal system — never quite panned out. Although there are more than a dozen medical examiner systems operating in the U.S. to date, roughly half of the population is still under the jurisdiction of coroners, who are not required to have medical degrees or specialized training. And while there are nearly 40 forensic pathology training programs, there are not nearly enough trainees to adequately investigate all of the unnatural deaths each year. Perhaps most concerning, as much as forensic techniques have advanced over the years, none are infallible, and many are being questioned entirely.

Nonetheless, Lee left behind a lasting legacy. The Department of Legal Medicine at Harvard paved the way for other forensic pathology programs. Hundreds of police officers have been trained using her Nutshell Studies and the curriculum she developed for the Homicide Investigation Seminar. Her tireless efforts in both medicine and the law, as Melinek writes, “have made a whole world of a difference.”

Sarah Witman is a St. Louis-based science journalist. This post was originally published on Undark.

–

Comments welcome.

Posted on June 17, 2020