By Liz Willen/The Hechinger Report

Nachae Nez is a basketball star at the largest high school on the Navajo Nation, 17.5 million acres sprawling across parts of Arizona, New Mexico and Utah. He lives in a trailer next to his two grandmothers and earns grades good enough for a four-year college.

Yet on the morning of the SAT college admissions exam, Nachae drives to the testing site from his home near Chinle, Arizona, looks around – and drives away.

“I couldn’t see my future off the reservation,” he tells Michael Powell, author of the new book Canyon Dreams: A Basketball Season on the Navajo Nation, due out from Blue Rider Press this month.

Powell’s intimate portrayal of students, teachers and an inspirational coach at Chinle High School is an important contribution to the literature on an education crisis that’s affecting native youth.

Native Americans are routinely left out of the national education conversation, and yet they face some of the longest odds in getting through high school and college. In 2017, barely a fifth of American Indian and Alaska Native adults ages 18 to 24 were enrolled in college.

The book follows the Wildcat team through one dramatic basketball season on the largest Indian nation in the U.S., which Powell describes as an isolated world of “sacred peaks, spirits and clans” where homelessness, alcoholism and unemployment are as rampant as books and libraries are scarce.

Chinle High and its athletic center become a place for showers and meals for its many homeless students, he writes, “and with luck an adult who might put a hand on the rudder in rough waters.”

The push and pull of reservation life, with its ancestral force, spiritual traditions and many contradictions, consumes the team as they hunt for an elusive state championship.

Powell writes with intense empathy about the limited choices and chances players face after their glory days at Chinle High. Less than half of Chinle graduates attend college, and of those who do, half drop out within a year or two.

Related: Why are tribal college students slow to ask for financial aid?

High poverty rates and inadequate schools have contributed to dismal achievement levels for native students, routinely among the lowest in the country. American Indian and Alaska Native students are the least likely of any demographic group to graduate from high school, and their college graduation rate is just 39 percent.

Canyon Dreams grew from articles that Powell, a sports columnist, wrote for the New York Times about rez ball, a “quicksilver, sneaker-squeaking game of run, pass, cut and shoot, of spinning layups and quick and endless running” that is a staple of life on some reservations. Games draw thousands of fans, who drive up to 80 miles over canyons and mountains, waiting in long lines and packing high school gyms. There’s even a Netflix series based on Powell’s articles.

But the book gives equal attention to players as they consider their futures off the court. Powell, a former colleague of mine at the now-defunct New York Newsday, cares deeply about education, and his writing sheds light on why many native students – even some who are high academic achievers – don’t head off to college.

There’s not much in the way of a college-going culture at Chinle High, beyond the unsung efforts of a handful of exemplary coaches and teachers. Arizona, like many parts of the country, has a dearth of school counselors, a topic we at The Hechinger Report have covered extensively. The state has the worst ratio of students to school counselors in the U.S., 905 to 1.

The players Powell gets to know are often deeply ambivalent about leaving their home, elders, siblings and extended families. In one scene, Powell drives to the home of Wildcat player Elijah James, down a dirt road “in a depression of salt flats and blue shale and barn-red clay that went by the improbable name of Beautiful Valley.”

Powell asks: “You are a senior. What do you want to do after high school?”

Elijah answers that he wants to go to college and maybe become a draftsman, but isn’t sure if he’s willing to leave the reservation; he tells Powell that it’s “my puzzle.”

U.S. universities have a complicated relationship with native people, often having been built on land taken from American Indians. These institutions remain predominantly white, and many colleges are just beginning to recognize the need to recruit and support indigenous young people. But as teachers and coaches in Powell’s book note, staying on the reservation can be as fraught as leaving.

Good jobs near Chinle are few; many end up chopping mesquite and pinon, herding sheep or traveling across state borders for construction jobs. Looking for work on the reservation is like “wandering in search of a desert spring,” Powell writes. Yet many of the students he got to know spoke of wanting to obtain new skills that would help their families and the Navajo Nation for years to come.

Related: How a struggling school for native Americans doubled its graduation rate

There are heroes behind the scenes, though, who help answer the question Powell poses early on: “How to find the courage to step out of Navajo and into the unknown?”

There is Shaun Martin, the athletic director and rural teacher of the year, a man who built the cross-country team into a powerhouse and who becomes an informal college counselor and surrogate father.

When college deadlines loom for his runners, writes Powell, Martin “labored late into the night on their applications and laughed with and cemented relationships with college coaches.”

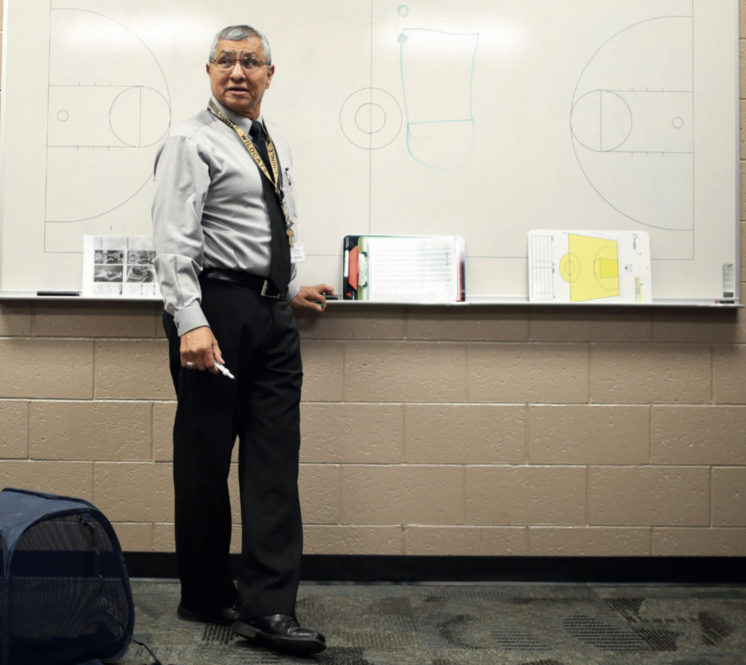

There is legendary Wildcats basketball coach Raul Mendoza, who has coached native basketball teams for 50 years and worked as a guidance counselor, motivated in part by nearly having his own school dreams crushed by a counselor in his native Mexico who laughed at him when he said he wanted to go to college.

Raul Mendoza/Courtesy of Nathaniel Brooks

Raul Mendoza/Courtesy of Nathaniel Brooks

Mendoza went on to graduate from Eastern Arizona College, where he met his Navajo wife. He is understated but forceful in asking his players what they want to do and be after high school. Will they be content, he asks, to hang out at the local supermarket, live at home and wait for their grandmother’s government checks?

Less than half of Chinle High School graduates attend college, and of those who do, half drop out within a year or two.

“When I graduated high school, I didn’t know what wanted, but I knew it had to be more than what I had, which was nothing at all,” the coach tells them.

Then there’s English teacher Parsifal Smith-Hill, a former surfer and cliff climber who pushes students to apply for scholarships in parts of the country most have never seen. Smith-Hill pushes hard to remind students about college admissions exams and loan applications and essays, and his top students routinely get into great colleges.

One of them is Chinle’s 2018 valedictorian, Keanu Gorman, who reads Greek mythology and Bronte, Wilde and Homer by the light of religious candles and types his college essays on his cell phone. We learn that Keanu is accepted everywhere he applies; he’s now a sophomore at Harvard.

Related: Tribal colleges give poor return on more than $100 million in federal money

Relying solely on heroic teachers and coaches to push a college education is not a sustainable strategy, however, and I asked Powell what he thought about the limited opportunities and obstacles that keep so many native youth close to home.

“The problem with relying on heroes is most of us are not heroes,” Powell told me.

A better solution would be highly trained and well-paid teachers and guidance counselors who understand reservation life yet “can work with families and let them know there’s a world out there, that going away to a four-year school is not betraying your culture,” he said.

Chinle High senior Cooper Burbank shooting hoops with his younger brother/Courtesy of Caitlin O’Hara

Chinle High senior Cooper Burbank shooting hoops with his younger brother/Courtesy of Caitlin O’Hara

Readers of Canyon Dreams will want to know what happens to students like Cooper Burbank, the Wildcat’s high-scoring captain who says in a student-athlete profile that his goal is to obtain bachelor’s and master’s degrees in engineering.

“As a Native American, we do not always have the most exposure or opportunities,” Cooper writes. “However, I feel like if I can excel in the classroom and on the court, it will allow more doors to be opened to play basketball beyond high school.”

And what of Nachae Nez, the former Wildcat captain whom Powell visits a year after his graduation? Because he can’t complete his application to the University of New Mexico without submitting SATs, Nachae instead ends up working at a pawn shop in the state and taking night classes at community college, while cheering on his former teammates from afar, over internet radio.

Will Nachae continue on to play ball at a four-year college or go back to the reservation? We don’t find out, but Powell points out one of the many contradictions of this sacred ancestral land: If Nachae comes back, he’ll be welcomed.

“Returnees get loving hugs from aunties and manly handshakes from uncles, and after few months of watching the wind whip sand snakes off mesas and feeling the razor wind of winter, many wonder: Now what?”

That question is at the heart of why more attention needs to be paid to education on the reservation and beyond, and Powell’s book is a great start.

This post was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s newsletter.

–

Comments welcome.

Posted on November 12, 2019