By Cathy Schlund-Vials/The Conversation

In America’s imagination, the Vietnam War is not so much celebrated as it is assiduously contemplated. This inward-looking approach is reflected in films like The Deer Hunter and Apocalypse Now, best-selling novels and popular memoirs that dwell on the psychological impact of the war.

Was the war worth the cost, human and otherwise? Was it a winnable war or doomed from the outset? What are its lessons and legacies?

These questions also underpin Ken Burns’ Vietnam War documentary, which premiered Sunday. But many forget that before the Vietnam War ended as a Cold War quagmire, it began as a clear-eyed anti-communist endeavor.

As a child, I was always fascinated by comics; now, as a cultural studies scholar, I’ve been able to fuse this passion with an interest in war narratives.

Comics – more than any medium – reflect the narrative trajectory of the war, and how the American public evolved from being generally supportive of the war to ambivalent about its purpose and prospects.

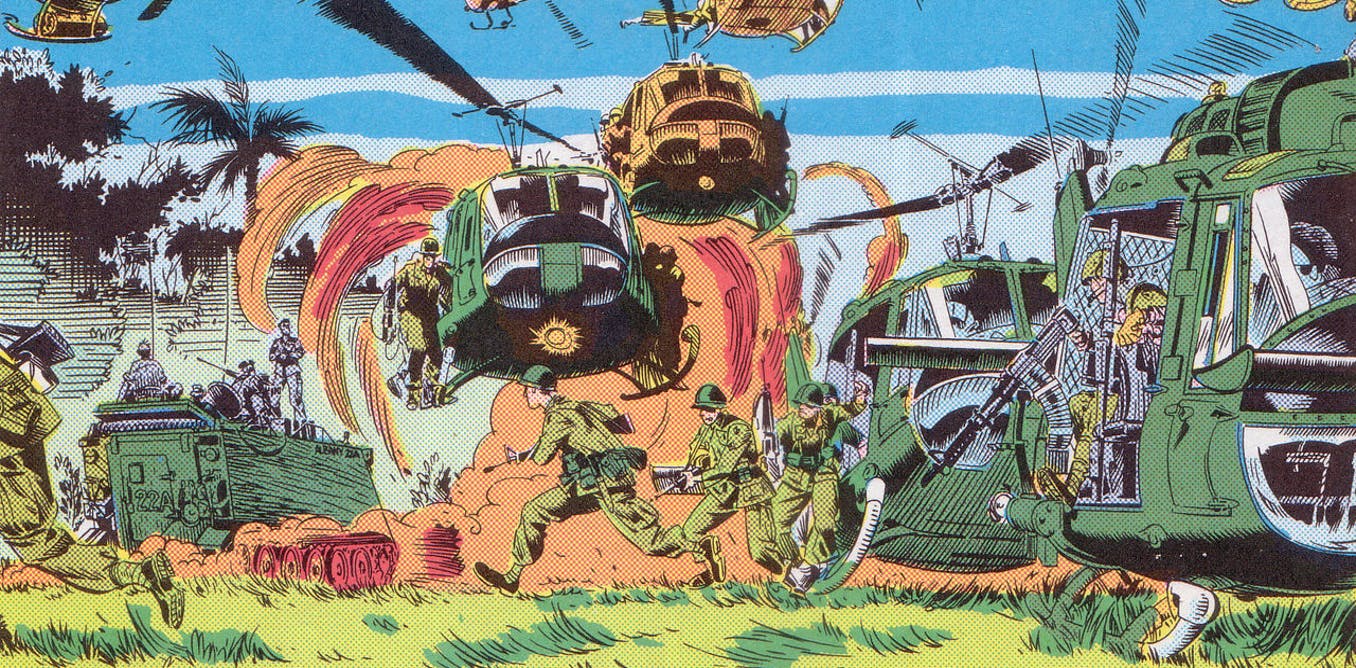

A panel from the Marvel Comics series The ‘Nam/Marvel Comics

A panel from the Marvel Comics series The ‘Nam/Marvel Comics

The Voice Of The People

Histories of war are often told through the major battles and the views of the generals and politicians in power.

American comics, on the other hand, tend to reflect the popular attitudes of the era in which they are produced. Due to serialization and mass production, they’re uniquely equipped to respond to changing dynamics and shifting politics.

During the Great Depression, Superman battled corrupt landlords. At the height of World War II, Captain America clashed with the fascist Red Skull. Tony Stark’s transformation into Iron Man occurred alongside the growth of the military industrial complex during the Cold War. And the diverse team of X-Men first appeared during the civil rights movement. These storylines reflect the shifting attitudes of regular people, the target audience of these comics.

More recent plots have included Tea Party rallies, failed peace missions in Iran and coming-out stories – all of which underscore the fact that comics continue to engage with current affairs and politics.

As modes of “modern memory,” comics – to quote French historian Pierre Nora – “confront us with the brutal realization of the difference of real memory . . . and history, which is how our hopelessly forgetful modern societies, propelled by change, organize the past.”

In other words, comics are a type of historical record; they’re a window into what people were thinking and how they were interpreting events – almost in real time.

From Hawks To Doves

The comics produced in the years during, after and leading up to the Vietnam War were no different.

The conflict, its soldiers and its returning veterans appear in mainstream comics franchises such as The Amazing Spider Man, Iron Man, Punisher, Thor, The X-Men and Daredevil. But the portrayal of soldiers – and the war – shifted considerably over the course of the conflict.

Prior to 1968 and the Tet Offensive, Marvel comics tended to feature pro-war plots that involved superhero battles involving U.S. compatriots and the South Vietnamese National Liberation Front battling Ho Chi Minh’s communist forces. These Manichean plots were reminiscent of World War II comics, wherein the “good guys” were clearly distinguished from their evil counterparts.

But as the anti-war protest movement started to gain momentum – and as public opinion about the conflict turned – the focus of such works shifted from heroic campaigns to traumatic aftermaths. More often than not, these included storylines about returning Vietnam War veterans, who struggled to return to civilian life, who were haunted by the horrors of conflict and who often lamented those “left behind” (namely their South Vietnamese allies).

Such transformations – superhero hawks becoming everyday doves – actually foreshadowed a common trauma trope in the Hollywood films that would be made about the war.

No ‘Supermen’ in The ‘Nam

Marvel Comics’ The ‘Nam (1986-1993), written and edited by Vietnam War veterans Doug Murray and Larry Hama, reflects the medium’s ability to narrate the past while addressing the politics of the present. The plots, for example, balanced the early jingoism with a now familiar, post-conflict cynicism.

Each issue was chronological – spanning 1966 to 1972 – and told from the point of view of a soldier named Ed Marks.

As Hama wrote in the introduction to Volume One, “Every time a month went by in the real world, a month went by in the comic . . . It had to be about the guys on the ground who got jungle rot, malaria, and dysentery. It had to be about people, not ideas, and the people had to be real, not cardboard heroes or super-men.”

The ‘Nam’s 84 issues placed historical events such as the Tet Offensive alongside personal stories involving “search and destroy” campaigns, conflicts with commanding officers, and love affairs.

The ‘Nam’s initial success was critical and commercial: the inaugural December 1986 issue outsold a concurrent installment of the widely popular X-Men series.

While Jan Scruggs, president of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial fund, questioned whether the war should be the subject of a comic book, Newsweek editor William Broyles praised the series, noting its “gritty reality.”

The most telling praise came from Bravo Organization, a notable Vietnam veterans’ group. The ‘Nam was recognized by the organization as the “best media portrayal of the Vietnam War,” beating out Oliver Stone’s Platoon.

As works of art, the Vietnam War comics are only one of many places the Vietnam War has been restaged, remembered and recollected. One of the war’s enduring legacies is the way it has inspired its veterans, its victims and its historians to try to piece together a portrait of what actually happened – an ongoing process that continues with Burns’ documentary. There has been no universal consensus, no final word.

As Pulitizer Prize-winning author Viet Thanh Nguyen wrote, “All wars are fought twice. The first time on the battlefield, the second time in memory.”

Cathy Schlund-Vials is a professor of English and Asian-American Studies at the University of Connecticut. This article was originally published on The Conversation.

–

See also: The Beachwood vs. Ken Burns’ Vietnam.

–

Comments welcome.

![]()

Posted on September 20, 2017