By Steven Lubet/The Conversation

President Donald Trump has exercised the pardon power more aggressively and creatively than most of his predecessors, granting pardons to political supporters such as Joe Arpaio and Dinesh D’Souza, and a posthumous pardon to Jack Johnson, the first black heavyweight champion, who was convicted on a racially fraught charge of violating the Mann Act.

Trump has mused about pardoning Rod Blagojevich, as well as Robert Mueller probe targets Michael Cohen and Paul Manafort. He’s even suggested he may pardon himself. And it is unlikely that he is done. The president has asked NFL players to suggest other possible pardon recipients who have been “unfairly treated by the justice system.”

I may not be a member of the NFL, but I do have a recommendation of my own.

A Pardonable Offense

In the spring of 1859, Charles Langston and Simeon Bushnell were convicted in a Cleveland federal court of violating the Fugitive Slave Act, which allowed slave hunters to “recapture” their human quarry in the northern states. Their crime was participating in the rescue of John Price, a runaway from Kentucky who had been apprehended by slave hunters on the outskirts of Oberlin, Ohio.

The event, which drew international attention, was known as the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue. As I explain in my book, Fugitive Justice: Runaways, Rescuers, and Slavery on Trial, it was one of the many small acts of resistance that eventually led to the Civil War, and thus to emancipation.

That Charles Langston was involved in the rescue should not have surprised anyone. Langston was born in Virginia in 1818, the son of white plantation owner and Revolutionary War veteran Ralph Quarles. His mother was an enslaved woman named Lucy Langston. Ralph and Lucy lived openly together and might even have married if Virginia law had allowed it.

Quarles recognized the couple’s children as his own, providing them with private tutors and freeing them, along with their mother, in his lifetime. Quarles left his entire estate to his children with Lucy, and arranged for them to move to Ohio at his death, so that they could live in a free state.

Langston grew to adulthood in Ohio, graduating from Oberlin College and embarking on a successful career as a teacher and journalist, while becoming a leader in the abolitionist movement. In 1853, he was elected executive secretary of the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society – a position previously reserved for white men.

Later that year he served as a delegate to the National Black Convention in Rochester, New York, where he befriended Frederick Douglass. Like Douglass, Langston rejected the pacifism of many white abolitionists. He openly carried a pistol on his lecture tours, daring racists to challenge him.

A Kidnapping And A Rescue

On September 13, 1858, John Price, a farm laborer in his mid-20s, was kidnapped on a country road in northern Ohio. A posse of slave hunters led by a Kentuckian named Anderson Jennings hustled him into a wagon and headed for nearby Wellington, where they planned to take the next train south. Their first stop would have been Columbus, where they expected to obtain a “certificate of removal” from a cooperative fugitive slave commissioner, authorizing them to return Price to slavery in Kentucky.

Fortunately, the abduction was witnessed by an Oberlin student named Ansel Lyman, who raced back to town and raised the alarm.

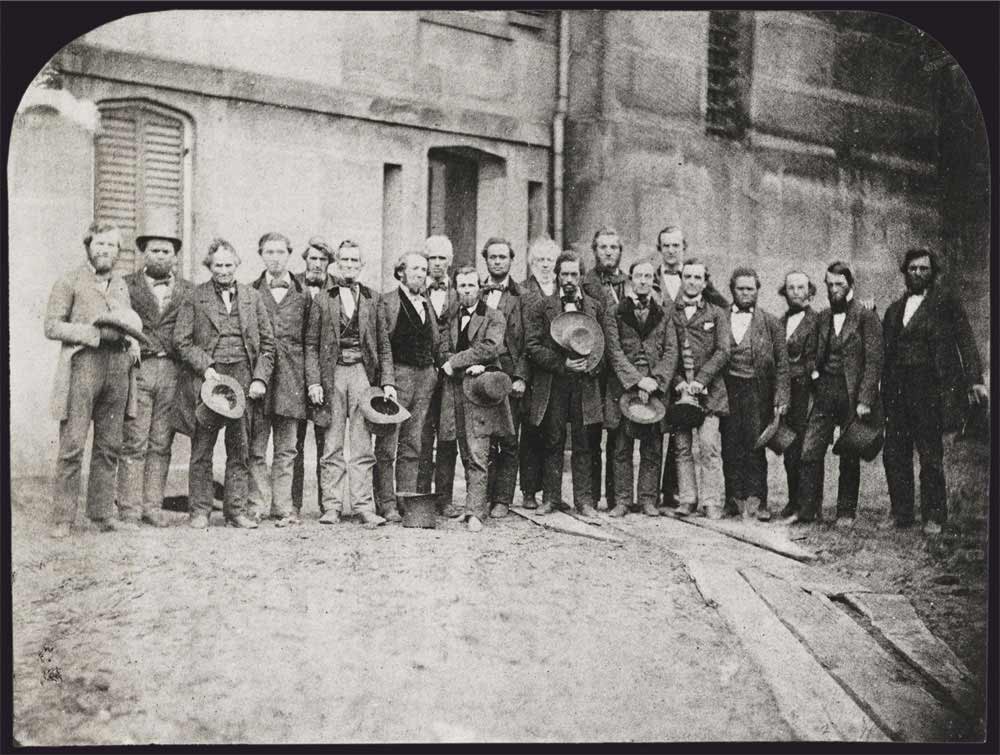

Oberlin rescuers, with Simeon Bushnell and Charles Langston 9th and 12th from the left/Library of Congress

Oberlin rescuers, with Simeon Bushnell and Charles Langston 9th and 12th from the left/Library of Congress

Hundreds of Oberliners, both black and white, quickly set off for Wellington, where they surrounded the kidnappers, who were holding their prisoner in a hotel near the railroad depot.

Langston attempted to negotiate with Jennings, explaining that he had no chance of reaching the train station. The slave hunter was intransigent, relying on a rumor that federal troops had been summoned to break up the mob. Langston warned the Kentuckian that the Oberliners would never allow Price to be returned to slavery and ended the negotiation.

As the crowd became more agitated, two groups of Oberlin students rushed the hotel, knocked down Jennings and his men, and carried Price to a waiting wagon – driven by young Simeon Bushnell – that bore him triumphantly to Oberlin.

Appealing To A Higher Law

Such open defiance was more than the pro-slavery Buchanan administration could tolerate. Indictments were issued against Langston and Bushnell, along with 35 others who had participated in the rescue to varying degrees, for violating the Fugitive Slave Act.

Langston and Bushnell were the first two defendants to face trial in the Cleveland federal court. The prosecutor referred to the defendants as “outraging the law of the land” and threatening to “tear down and annihilate the government of these United States.” The defense boldly replied that “slavery is like a canker” that must give way to “Higher Law.” The jury members, who had been hand-selected for their approval of the Fugitive Slave Act, did not take long to return the predictable convictions.

Bushnell, who was a white bookstore clerk, stood mute at sentencing. Langston, however, took full advantage of the platform and spoke to the nation.

He condemned the slave hunters as “lying hidden and skulking about” and he praised the fugitives “who had become free . . . by the exercise of their own God-given powers – by escaping from the plantations of their masters.”

Rebuking the court itself for racism, he expressed no contrition and virtually promised to continue rescuing fugitives.

“If ever a man is seized near me, and is about to be carried South,” he said, “I stand here to say that I will do all I can, for any man thus seized and held.”

The judge was moved by Langston’s eloquence, which led him to impose a less-than-maximum jail sentence and fine. Even more impressed was John Brown, who paid close attention to the trial, and later obtained Langston’s assistance recruiting two black Oberliners for the raid on Harpers Ferry.

John Price was spirited to Canada by another anti-slavery activist, John Anthony Copeland, where he was reported by Langston’s brother, John Mercer Langston, to repose “under his own vine and fig tree, with no one to make him afraid.”

Little is known of Simeon Bushnell’s later life, but Charles Langston became the patriarch of a prominent African-American family. His younger brother, John Mercer Langston, was the first dean of Howard Law School, appointed U.S. ambassador to Haiti, and elected to a term in Congress from Virginia. Charles’s grandson, as some readers may have intuited, was the poet and playwright Langston Hughes.

Charles Langston and Simeon Bushnell were convicted for participating in a noble act that should never have been a crime. Few Americans have been more “unfairly treated by the justice system,” or are more deserving of a posthumous pardon.

Steven Lubet is a law professor at Northwestern. This article was originally published on The Conversation.

–

Comments welcome.

![]()

Posted on July 31, 2018