By Roger Wallenstein

When Phil Lucas’s daddy jumped a train in Alabama in October of 1946 heading to St. Louis for the National League playoff between the Cardinals and Dodgers, he couldn’t have known that his escapade would have long-term repercussions for his unborn son.

The Cardinals beat the Dodgers 4-2 that fall afternoon, and two days later they wrapped up the NL pennant by thumping Brooklyn 8-4 in the best two-of-three playoff.

Although Lucas, a history professor at Cornell College in Mt. Vernon, Iowa, grew up outside of Philadelphia, listening to his father talk about that 1946 playoff resulted in Phil becoming a lifelong Cardinal fan.

Not only that, Lucas has had a passion for the game’s origins, history and role in American society almost as long as he’s cheered for the Redbirds. Lucas’s expertise is American history from colonial times through Reconstruction, but he’s managed to share his love of baseball by offering a course, Baseball: The American Game, once every three years since 1984.

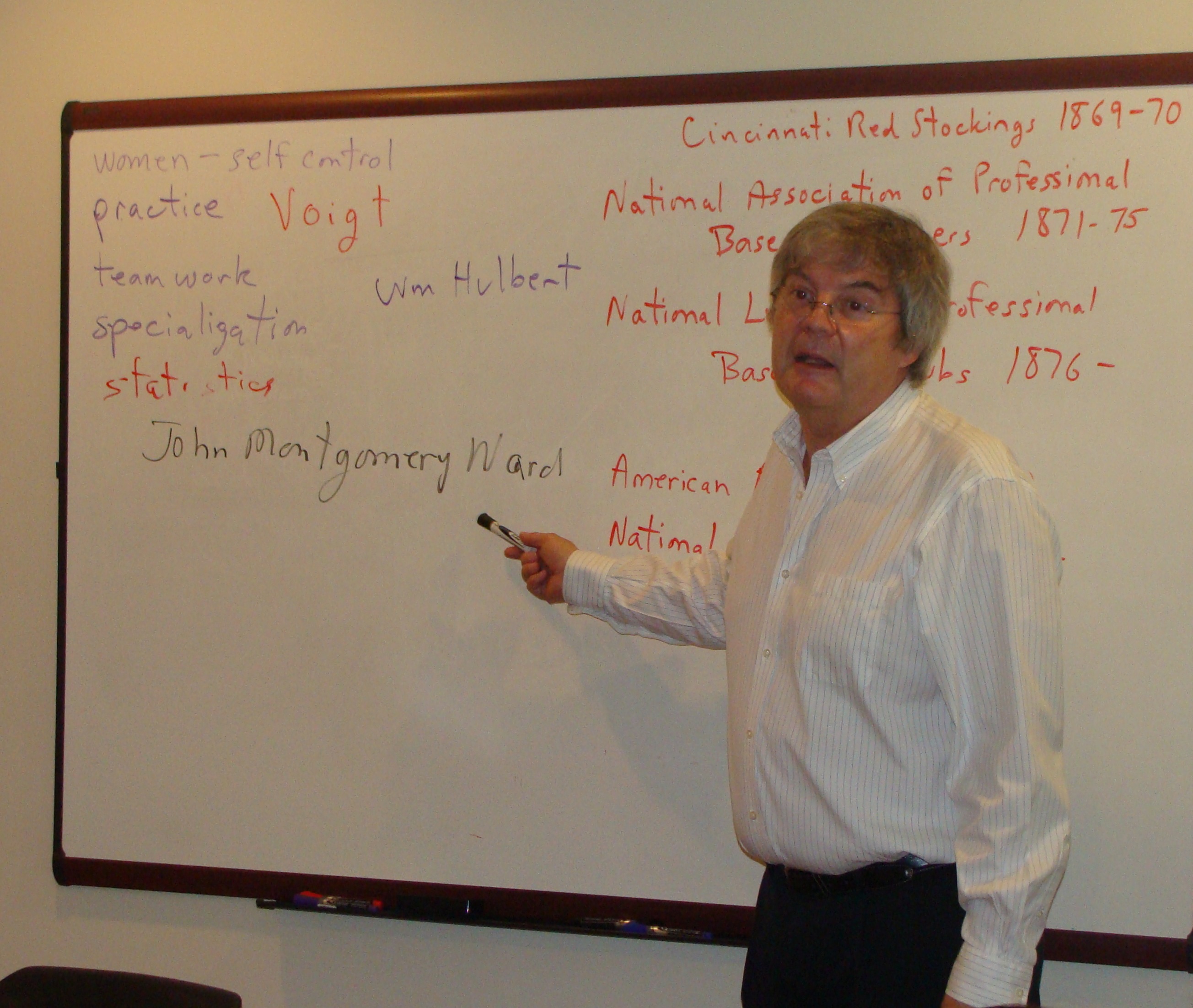

Photo courtesy of Cornell College

“It’s fully enrolled,” he told me last week.

Lucas was in Chicago leading a two-day mini-course for Cornell alumni billed as The History of Baseball. I attended the small (enrollment 1,200) Midwestern college my freshman year, although my brother is a graduate. So together we joined four alums from the ’60s along with a mix of other alumni including three members of the Class of 2013.

Included in the curriculum was a trip to Wrigley Field last Thursday to watch the Cubs complete their three-game sweep of the White Sox. I spent most of the afternoon looking at a post with the number “236” painted on it, which obscured my view of the pitcher.

That’s the bad news.

The good news is that I never saw Jake Peavy release one pitch in his four-inning, six-run outing which included serving up a grand slam homer to opposing pitcher Travis Wood in the Sox 8-3 embarrassment. More about our woeful athletes in a moment, but let’s first talk about the far more interesting information that Lucas shared.

Pinpointing the “invention” of baseball is a tricky business, and chances are that Abner Doubleday was far from the icon who molded the rules and regulations of the game. Lucas reminded us that “we know that the Egyptians had bat and ball games,” and similar recreation was practiced throughout Medieval times.

As he mused about the origins, I wondered whether the Pharaoh would have offered Adam Dunn the kind of contact he received three years ago from the Sox. I suspect not. Pharaoh had more sense.

What does seem clear is that we have Alexander Cartwright to thank for doing things like creating the diamond-shaped field in 1845, along with the concept of fair and foul territory. Prior to Cartwright, a member of the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club of New York, there could be as many as 20 players on a side, positioned willy-nilly throughout the real estate.

Again, my mind wandered. The Sox really could benefit from being able to have, say, 15 guys in the field. If Robin Ventura could use six outfielders and a backup catcher behind Tyler Flowers, there’s no way our team would be last in fielding in the American League.

Cartwright or an able-bodied Knickerbocker then stepped off the distance between home plate and second base as well as first and third. They came up with 45 paces, which, lo and behold, created a ballfield where the bases were 90 feet apart. Lucas said there may have been some trial and error on this one, but the final outcome was basically what we have today. I find that absolutely fascinating.

It also was helpful in getting Cartwright elected to the Hall of Fame in 1938, and in 1953 the U.S. Congress “officially declared” that Cartwright invented the modern game of baseball. Of course, that was back in the day when Congress actually did something.

Lucas covered lots more during the two days of class including the ways in which baseball morphed from a game played with professionals rather than amateurs in the 1870s; the formation of the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players in 1876 (which later became the National League); and Ban Johnson’s creation of the Western League in 1901, the forerunner of the American League a year later. The class also touched on the reserve clause and integration before time ran out on Friday.

As readers may be aware, the present-day White Sox just got swept over the weekend in Oakland. We know that the Sox were shut out Friday and Sunday, losing 3-0 and 2-0, respectively. Together with the 4-3 10-inning loss on Saturday, the team hit just .184 in the three-game series and wasted strong starting pitching by Dylan Axelrod on Saturday and Chris Sale on Sunday.

What you may not know is the significance of that elephant on the left sleeve of the A’s uniforms. I’ve seen it for decades and never could figure it out.

However, now I know.

The first World Series was played in 1903 with the Boston Americans beating the Pittsburgh Pirates. The next season John McGraw’s New York Giants won the National League pennant and were slated to play the American League champion Philadelphia Athletics, who eventually moved to Kansas City and then to Oakland.

But McGraw was a proud, chauvinistic individual, and the thought of engaging an inferior squad like the A’s was beneath the dignity of his Giants. “He called them a bunch of white elephants,” Lucas told us. So there was no World Series in 1904 because the Giants refused to participate. But the elephant logo became a standard for the Athletics’ uniforms.

I’m not sure that Oakland outfielder Yoenis Cespedes knows why he’s wearing an elephant on his sleeve, nor was that knowledge necessary as Cespedes and his teammates subdued the Sox over the weekend to conclude one of the most dismal weeks in White Sox history.

With six consecutive losses in the books – it well might have been seven if Tuesday night’s game hadn’t been rained out with the Sox trailing 2-0 – the South Siders are last in the American League in batting average (.237), on-base percentage (.289), runs (20 fewer than anyone else), hits (29 fewer than No. 14 Seattle), and bases on balls. They swing – usually unsuccessfully – at just about anything: strikes, change-ups and breaking balls in the dirt, and fastballs at the shoulders and higher.

Failing to beat the Cubs rubbed salt – not regular salt but that coarse, cubed, potent Kosher salt – into the wound. The Sox didn’t even come close, being outscored 26-6 if you include the postponed contest. One would have to scour Sox annals to find a week when the team played as poorly as they did the past seven days.

The Knickerbocker Base Ball Club of New York would have feasted on this sorry bunch.

At least baseball was glowing over on North Seminary at Cornell’s McLennan Center, a converted two-flat where our class met.

“It’s not the only [college class about baseball history],” said Lucas. “But I’ve received requests for my syllabus from a number of people.”

It’s a fine syllabus with one notable flaw: watching the Sox play.

–

Roger Wallenstein is our man on the White Sox. He welcomes your comments.

Posted on June 3, 2013