By Roger Wallenstein

He may not have realized it at the time, but my brother John created the model for the Excel spreadsheet almost 30 years before Microsoft unveiled it. All because of the White Sox.

The season was 1959, and because “it just needed to be done,” Brother John began keeping day-to-day statistics – both hitting and pitching – for the eventual American League champions. For all 154 games, he began in the upper left hand corner of a clean sheet of notebook paper with Aparicio and Arias, ending with Torgeson and Wynn. IBM engineers may have begun experimenting with a copying machine, but it took them another ten years to market one. So John spent a part of each day re-creating his spreadsheet. Ask him today to recite the entire ’59 roster, especially after a couple glasses of wine, and he’ll give it to you in alphabetical order.

This compulsive behavior may have raised questions for mom and dad, but no shrink was consulted. Left to his own devices, John repeated the feat for the 1960 campaign.

Therefore, it probably will come as little surprise that my brother, who wrote a master’s thesis on baseball and the antitrust laws, found employment in the game in 1969 – as a minor league executive. He began in Indianapolis, and over the next dozen years he stopped in Cedar Rapids, Wichita, Tulsa, New Orleans, and Springfield, Illinois, where he’s lived for the past 30 years. When he had a chance to get back into the business in 1998, John became the general manager of an independent league ballclub in Springfield for another four seasons.

Bull Durham’s Annie Savoy said, “I believe in the Church of Baseball,” and that pretty much summarizes my brother’s passion. Annie had lots of stories. So does John, including a few he’d like to forget.

For example, as the 28-year-old general manager of the Single-A Cedar Rapids Cardinals of the Midwest League, John leaned toward hiring a company which offered mass phone solicitations to sell tickets. His board of directors didn’t share his enthusiasm for this boiler room operation.

“They didn’t want to bother the people,” he recalls. “They thought it was not right, and they were the bosses.”

Our dad, who was a career salesman, advised John to back off. “Dad said you’re going to get fired if you go ahead and do it,” John says. “But I did, and I was.”

Undaunted, he got back into the game after interviewing with Wichita Aeros GM Joe Ryan, a veteran of minor league front offices. Included on Ryan’s resume was a stint as business manager of the Miami Marlins in the mid-50s when Bill Veeck owned the club.

The Aeros were the Triple-A farm of the Indians, boasting a lineup that included future stars Chris Chambliss and Buddy Bell, the current vice president of player development for the White Sox.

Ryan’s lessons were simple. “The most important thing was to get the signature [for ticket sales and/or advertising] and get out,” John says. “Once you get the signature on a contract, nothing better could happen. And keep your mouth shut, that was another good one. Don’t talk too much.”

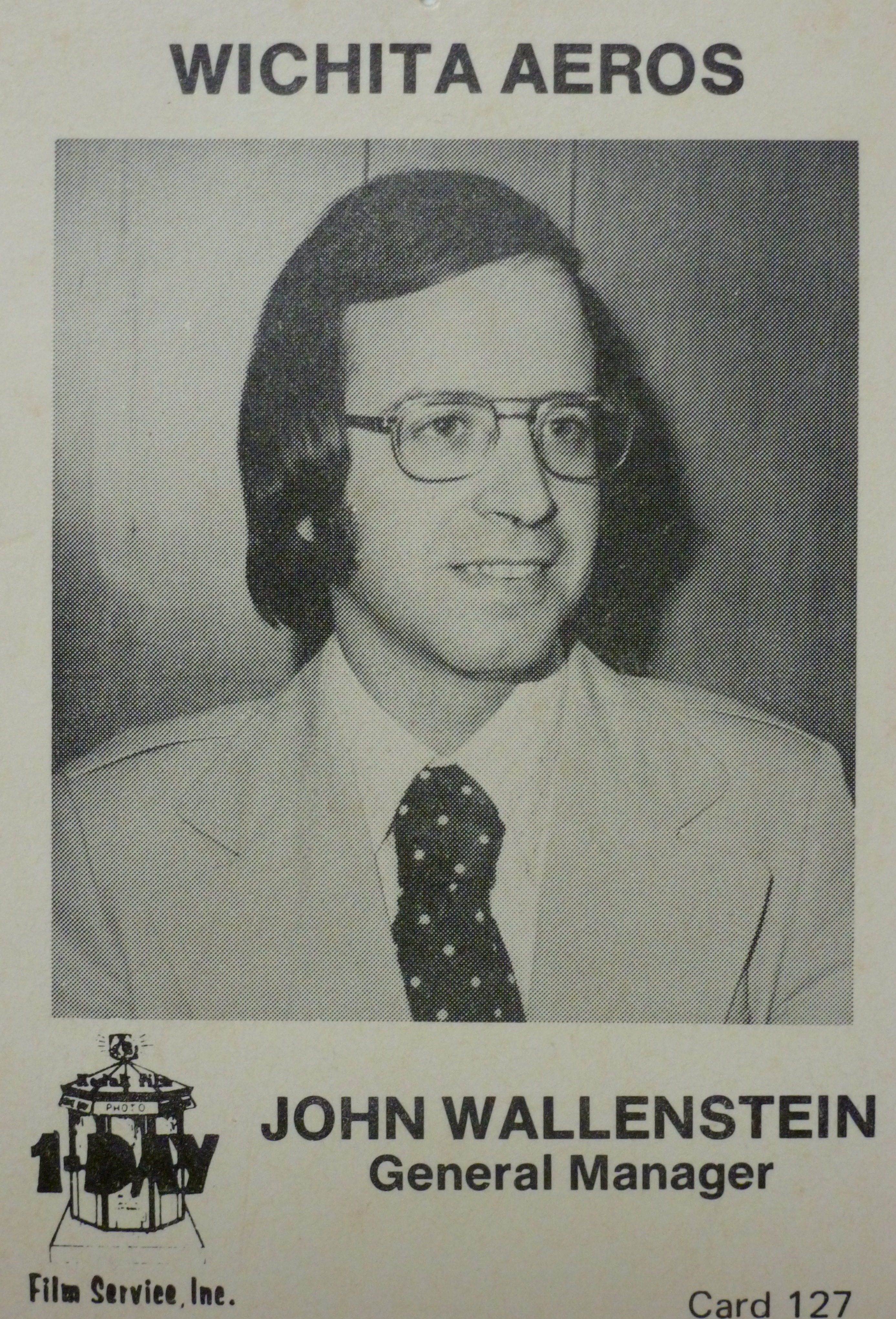

I met Joe Ryan a few times, and he lined me up with great seats for the 1983 All-Star Game at Comiskey Park. When Ryan succeeded pitching great Allie Reynolds as president of the American Association, John moved up to become general manager of the Aeros.

That’s when he began learning some new lessons. One concerned the clubhouse, a place he generally avoided.

“There were 25 of them and only one of me,” he says. “No player ever volunteered to give me anything, but lots of them asked me for stuff. We had an infielder who asked me for some bats, and I said, ‘Well, give me your broken ones.’ That was the deal because otherwise they’d just take the bats and give them to kids or to girlfriends for sex and stuff like that. You’d never see [the bats] again.

“He about killed me. ‘I make my living with that bat,’ he said. ‘I need bats.’ Actually he could have had all the bats in the world, but he still couldn’t hit.”

Another guy who couldn’t hit was Tony LaRussa, who played in Wichita in 1973 and later in New Orleans where John landed in 1977. Tony played parts of 15 seasons in the minors with a .265 average, but he hit just .199 in a brief major league career.

What kind of player was LaRussa? “Horrible,” John says. “He couldn’t run. He had those what I call Boccabella legs. He was a second baseman, and he just could not move.”

In Tony’s last season as a player in New Orleans, he was a marginal player. “He was like a Triple-A stabilizer,” John recalls. “He would always ask me, ‘John, have you heard anything?’ He was talking about being released.”

Was there any indication that LaRussa would go on to be third winningest manager in history? “I thought he might be [a manager] just because of his tenacity, his intelligence, and the fact that he was a decent human being. He treated me good. I liked him.”

Two years after hanging on in New Orleans, Tony LaRussa was manager of the Sox at age 34.

Perhaps the most memorable character in my brother’s baseball career was owner A. Ray Smith, a Texan who made his money in the construction business and later purchased the Tulsa Oilers. He hired John as business manager in 1975. I had lunch with Smith once, and every other sentence was filled with down-home, old-boy sayings that made those Hangover movies sound like Alice in Wonderland.

Smith tried to get the city leaders in Tulsa to build a new ballpark because the Oilers’ stadium was a broken-down wood structure badly in need of repairs. One night a fan fell through the floorboards up to his armpits with his feet dangling below.

“I came into the office a few minutes later and he was in there with his pants down and his wife was swabbing his ass,” John says “It was all scraped and bloody. His wife was taking care of him with a wet rag.”

Being a far less litigious society in those days, no lawsuit was filed, but New Orleans wanted a big league club, and Mr. Smith’s team was the next best thing. So with a decaying ballpark in Tulsa, he took his operation to The Big Easy, and they became the Pelicans for the ’77 season. Drawing a few thousand – if that many- fans in the cavernous Superdome and paying exorbitant rent sent Smith looking for a new home after one season, and he settled on downstate Springfield. That was my brother’s final (1978-81) stop as he and my sister-in-law Gracia felt that their three daughters needed more stability in their lives.

Before Smith relocated to Louisville, he was approached by a persistent clubhouse manager, Frank Coppenbarger, who worked for the Single-A Decatur Commodores but sought to move up to Triple-A Springfield.

“He wanted to be clubhouse manager,” says John. “He kept calling and calling and calling, and one day he came by for an interview, but Smith was non-committal. Then one day – it was in February – there was a huge snowstorm. We were pretty much marooned in the office, and here comes Frank Coppenbarger from Decatur to see if he got that job. As he was walking in, [secretary] Alice Neighbors said, ‘Mr. Smith, here comes that asshole from Decatur.’ He just shook his head and hired him.”

However, there are no seasonal jobs in minor league baseball. “To work full-time you couldn’t just do a baseball job,” explains John. “You had to be able to sell. He ended up being really good at that. Now he’s an executive with the Phillies and has been for years. He’s their travel secretary and clubhouse manager, and he’s got a couple of World Series checks.”

While my brother no longer works in baseball – he sells time for the NPR station in Springfield – he’s maintained the contacts. Without them, there would have been no way that we could have sat behind home plate for the 2005 postseason at the Cell. Nor could he have invited me to the third game of the ’04 World Series in St. Louis. As the Red Sox were en route to a sweep of the Cardinals on a cool, damp night in the old Busch Stadium, he turned to me and said, “I know this is the World Series, but I’d just as soon go to a Sox game in mid-July.”

I thought about that for a moment. I thought about all the games, the ballparks, and the people he had encountered along the way. And I remembered him scribbling down those names and adding in the figures each day. It has always been about the Sox.

“Yeah, me too,” I said.

–

Roger Wallenstein is our man on the White Sox beat. He welcomes your comments.

Posted on July 16, 2012