History hangs in the air the same way that the kudzu hugs the trees. Sitting in the first base grandstand, I closed my eyes for a few moments last Wednesday afternoon and tried to visualize Satchel Paige standing on the mound as a 20-year-old rookie in 1927. If that sounds somewhat peculiar, blame it on Rickwood Field.

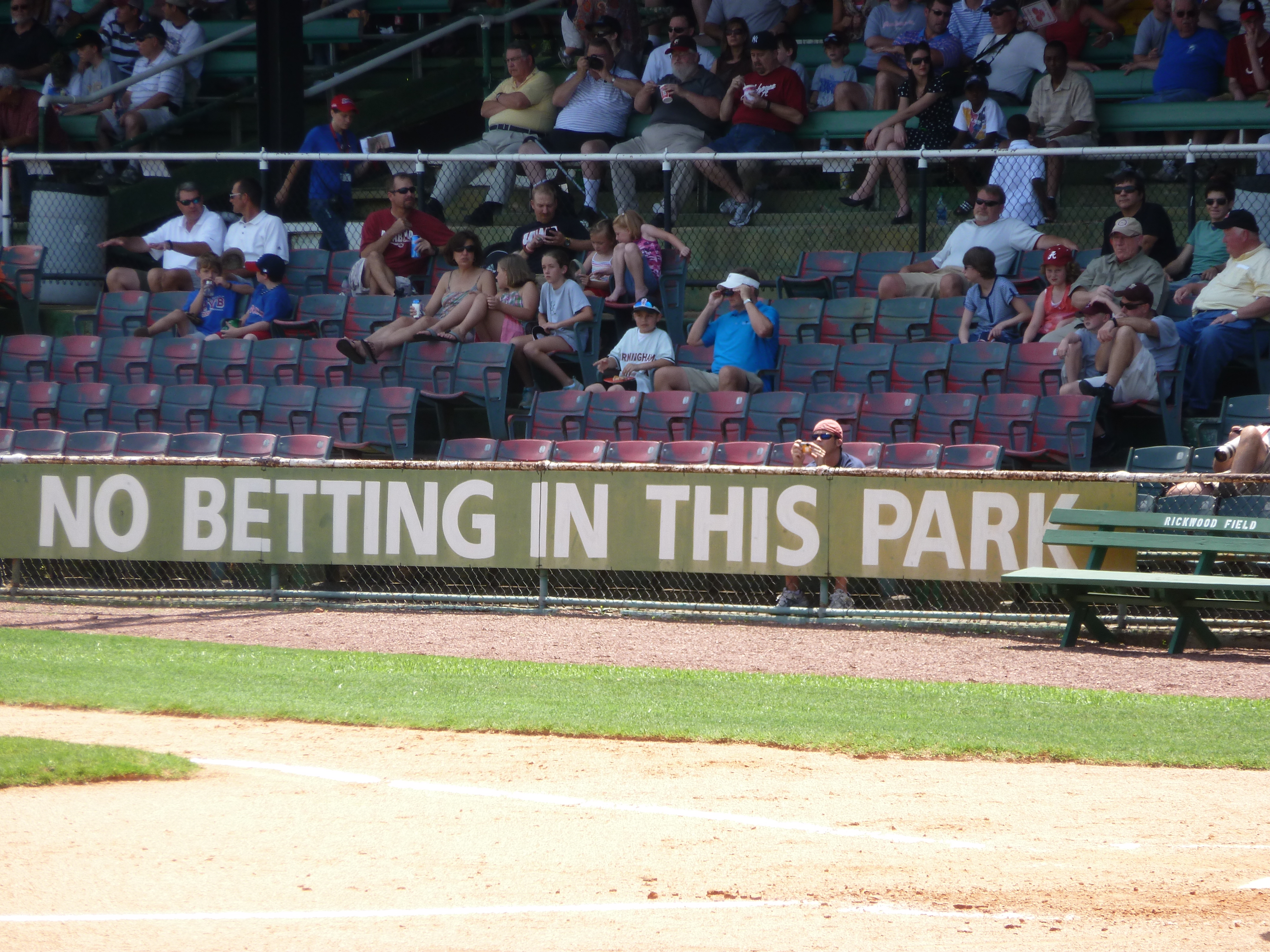

Billed as the oldest ballpark in America, Rickwood’s turnstiles first spun in 1910. Its rich tradition and history are a part of Birmingham, Alabama, where the steel and iron industries highlighted its early economy and where the civil rights movement gained a foothold, signaling genuine change in America.

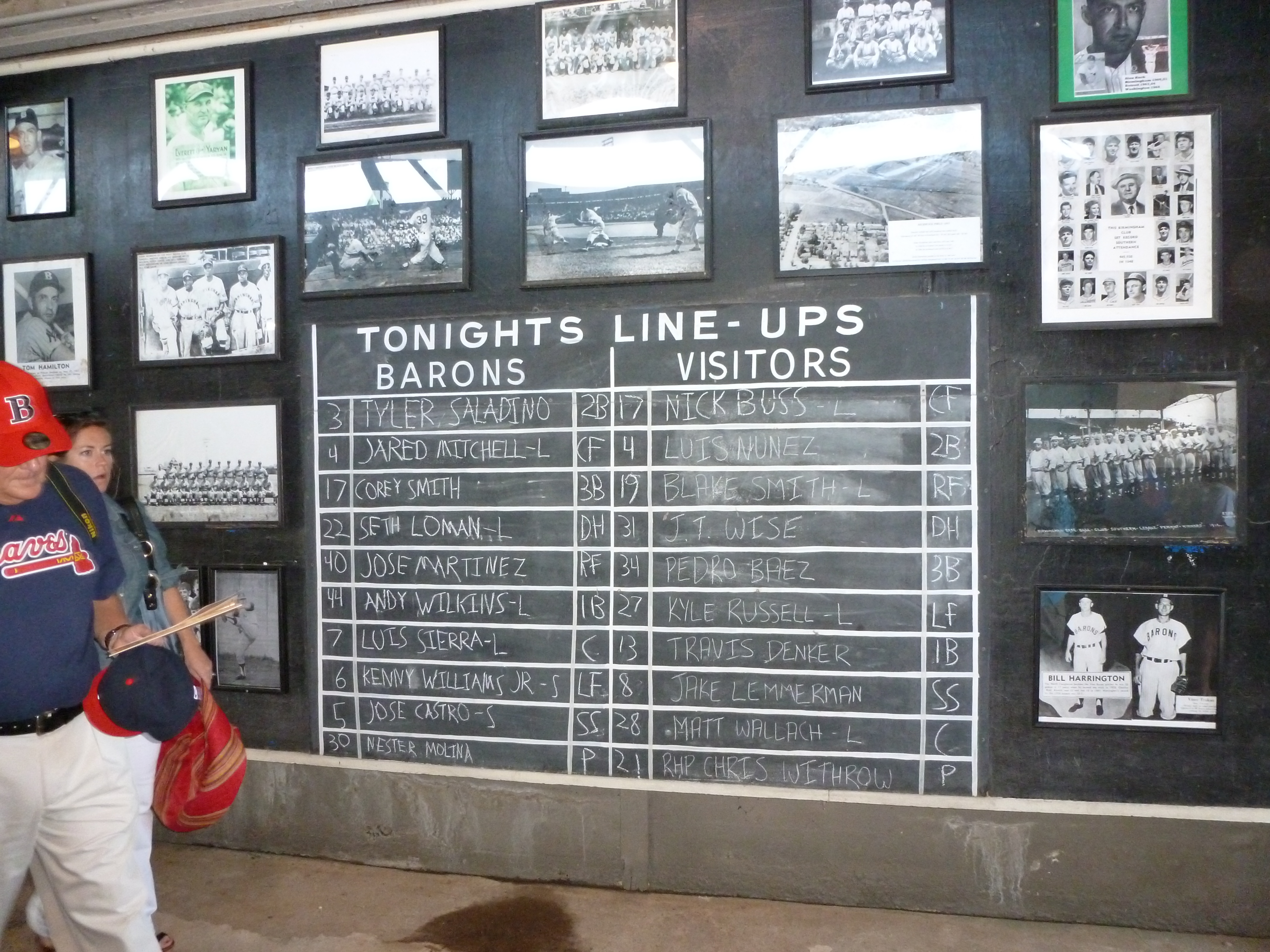

For the past 17 years, the Birmingham Barons, the White Sox’ Double-A affiliate, have staged the Rickwood Classic, a regular Southern League contest characterized by vintage uniforms, brass bands, and a few thousand fans – the announced crowd Wednesday was 7,180 – eager to hold onto and honor the past.

“I’ve played here since 2009, and just coming into Birmingham, you can just feel the history,” said Barons pitcher Henry Mabee. “We’re in the clubhouse, and it’s like a museum. Walking on the field, you can see [the history].”

Mabee has a point. The outfield fence is decorated with advertising from the 1930s and 40s. The scoreboard has been restored, listing teams like the Little Rock Travelers, New Orleans Pelicans, Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants. Imposing light towers, added in 1936, overhang the roof along the baselines.

Willie Mays, who played for the Negro League Black Barons in 1948, grew up nearby. Satchel pitched at Rickwood for parts of four seasons as a member of the Black Barons. Babe Ruth slammed a long home run over the right field wall as the Yankees played their way north from spring training. And Reggie Jackson’s final minor league layover in 1967 came at Rickwood as a member of the Birmingham A’s. Teammates included Rollie Fingers, Tony LaRussa, Dave Duncan, and Joe Rudi.

One criticism of today’s ballplayers is their lack of interest and knowledge about the history of the game. However, my wife Judy and I found Mabee mingling among the fans bent over the table of silent auction items about 45 minutes before the first pitch last week. His focus was on an autographed photo of Andre Dawson. Mabee, a Canadian from British Columbia who is having a stellar year with an ERA under 1.00, explained that his mother always admired Dawson, and he wanted to give her a belated Mother’s Day gift.

He was persistent. After his initial bid was topped, Henry returned and eventually got the photo for $75. Mom had to be pleased.

Mabee and his teammates, who dropped a 7-6 decision to the Chattanooga Lookouts (a Dodger affiliate), obviously represent today’s link to Rickwood. But they were easily outnumbered by representatives from the past.

Throwing out one of the ceremonial first pitches – former Atlanta star Dale Murphy was advertised as the main attraction – was 87-year-old Rev. William H. Greason. Years ago he was plain, old Bill Greason, pitcher for the Black Barons in 1948 and later with the St. Louis Cardinals. In fact, Greason was the second African-American signed by St. Louis – first baseman Tom Alston was the first – and he appeared in three games in 1954. All this occurred after he served in an all-black Marine unit that experienced combat on Iwo Jima.

“Did you play with Satchel Paige?” I asked.

“I played against him,” Greason said. “I was with the Rochester Red Wings, and he was with the Miami Marlins.”

The year was 1956 in the International League when Satch was 49 and Greason was 32. According to Rev. Greason, Satchel beat him 2-1.

“He was a tall fella; he had a good arm and he had unusual control,” Greason said. “He didn’t have no breaking stuff. He just had a good fastball and pinpoint control. He could throw that ball wherever he wanted. He was just a great pitcher, one of the best I’ve ever seen.”

Greason’s memories of playing at Rickwood are just as poignant.

“Every Sunday we played here, the house was packed,” he told me, adding that the deepest part of the outfield was roped off to accommodate standing-room-only fans.

Most, but not all, of the spectators were African-American.

“Over there in right field they had stands,” he said, pointing toward the foul pole. “When the whites played, that’s where the blacks sat, and when the blacks played, that’s where the whites sat. It didn’t bother us.”

Baseball in Birmingham in the 1940s was the only game in town. Rickwood’s capacity is 10,800, and the 1948 Barons drew 445,000 fans, which was 110,000 more than the American League’s St. Louis Browns.

Tom Russell, who was sitting in the row in front of us, remembered that season. “There were eight, 10, 12 thousand a game” he recalled. “Those were the days when they had street cars lined up bumper-to-bumper [in the street].”

Echoing Greason, Russell mentioned how fans stood in the outfield to view the games, especially the Dixie Series featuring the champions of the Southern Association and the Texas League. He also talked about a Birmingham clothier who offered a new suit for every Baron home run.

“Walt Dropo got about 37 suits,” laughed Russell. In reality, Dropo clubbed 14 round-trippers in 1948 and later was Rookie of the Year with the Red Sox in 1951 before playing for the White Sox in 1955-58.

“Television and the comforts of air conditioning” signaled the beginning of the end of capacity crowds, according to Russell, and segregated seating at Rickwood also fell by the wayside as Jim Crow began to take a beating.

“It wasn’t until Billy Graham came here with a crusade that there was mixed [seating],” he said.

We also made the acquaintance of Dean Self, who was sitting to Russell’s left. A missionary who spent 20 years in Bolivia, Self now ministers to a segment of Alabama’s 300,000 Latinos, including eight who play for the Barons. He serves as the team’s chaplain for Spanish-speaking players.

“My daddy brought me here [to Rickwood] when I was six,” he said. Once he returned from Bolivia eight years ago, Self quickly resumed attending Barons games. He had nice things to say about the current crop of players, including the day’s starting pitcher Nestor Molina, the 23-year-old Venezuelan whom the Sox obtained in the Sergio Santos trade with Toronto.

“He goes to church every Sunday,” said Self as we watched Molina pitch into the sixth inning, yielding four runs while striking out six. When the kid missed his spots, he got hit. When he had command, the other guys were swinging and missing.

The pitcher who was most impressive was Dominican reliever Santos Rodriguez, 24, who came to the Sox from Atlanta with Tyler Flowers and Brent Lillibridge in 2008 in exchange for Javi Vasquez and Boone Logan. The 6-5 left-hander pitched the ninth inning, displaying a live fastball as he struck out two of the three men he faced.

Outfielder Kenny Williams Jr. led the Barons’ attack with two line drive singles, driving in three runs. First-round draft choice (2009) Jared Mitchell had a rough day, going 0-for-4, while promising infielder Tyler Saladino looked good in the field while collecting a couple of hits.

However, the day belonged to grand, old Rickwood – its steel girders and concrete steps – along with the people who grew up watching baseball played in a pure, unspoiled setting. “The people here know the game,” mused Henry Mabee. “You get a feeling for it right away.”

–

Photos by Roger Wallenstein.

–

–

–

–

Roger Wallenstein is our man on the White Sox beat. He welcomes your comments.

Posted on June 4, 2012