By Steve Rhodes

TV One launched Find Our Missing this month with a show that included the cases of Austin teenager Yasmin Acree and the missing South Side Bradley sisters under the well-documented proposition that black girls – and poor black girls in particular – who have disappeared don’t get nearly the media coverage (if any) that white girls – pretty white girls in particular, and the wealthier the better – get.

“Find our Missing, launched Jan. 18, was designed to put names and faces to people of color, like Yasmin, who’ve disappeared without a trace. Each episode tells the story of a missing person or persons, beginning with the day they vanished and the frantic searches by loved ones and investigators to find them,” Austin Talks reports.

“Nearly one-third of the missing in this country are black Americans, while we make up only 12 percent of the population. Yet stories about missing people of color are rarely told in the national media,’ Wonya Lucas, president and CEO of TV One, the network airing the series, said in a press release.”

Point taken. But Acree’s case actually has attracted a fair amount of national media coverage, as we shall see, and her disappearance is more complicated than one may think, as we shall also see. And then you can check out TV One’s telling of her case.

*

On January 25, 2008, the Tribune reported:

Nine days after Yasmin Acree, 15, went missing from her Austin home , a local clergy group offered a $1,000 reward for information leading to her whereabouts.

Standing with Yasmin’s mother Thursday afternoon at Chicago Police Department headquarters, officials with the Leaders Network pleaded for Chicagoans to keep watch for the Austin Polytechnical Academy freshman.

Yasmin’s family reported her missing Jan. 16, after finding the locks on two outside gates cut and the door to the basement, where Yasmin’s bedroom is , forced open, said her mother, Rose Starnes.

Police, however, said there was no evidence of a break-in and that Yasmin told her friends she was planning to run away.

Police, who are investigating Yasmin’s disappearance as a missing persons case.

Starnes, who said she is certain her daughter was kidnapped, said the friend who claimed she planned to run away later recanted the statement.

On July 10, 2008, the Tribune reported:

Before she disappeared in January, Yasmin Acree talked excitedly about starting her first job and taking an annual summer trip with a YMCA mentoring program, which was considering her for a prominent role in a new job initiative.

“There are so many reasons why my daughter wouldn’t run away,” said Rose Starnes, who reported her 15-year-old daughter missing almost six months ago.

On Wednesday, family, friends and several ministers gathered in front of the Chicago Police Department’s Grand-Central headquarters on the West Side to urge officials to heighten their investigation into Acree’s disappearance.

“Because she’s a 15-year-old African-American honor student from the West Side, this case isn’t getting the attention it deserves,” said Rev. Marshall Hatch of New Mt. Pilgrim Missionary Baptist Church.

Acree’s family wonders why it took two days for police to gather what the family considers key evidence – a lock that may have been cut from a wrought-iron gate outside the missing teen’s home.

Chicago police spokeswoman Monique Bond said evidence technicians were at the scene in January and collected what they thought was appropriate. She said police have no suspects.

Grand-Central Cmdr. Joseph Salemme said Wednesday that the criticism was “a little insulting.” He said police have spent more than 2,000 hours on the case and sent numerous items to the state crime lab.

The investigation has gone into California and Kentucky, where other family members live, Bond said.

She also said police have not gotten full cooperation from people who may have information about the missing teen.

On September 11, 2009, the Tribune reported:

Chicago police on Thursday were trying to assure the family of a missing teenager that they continue to devote resources to the case after an internal investigation substantiated misconduct allegations against investigators.

More than a year after Yasmin Acree disappeared from her West Side home, Internal Affairs investigators sustained allegations by her family that the honor student’s disappearance wasn’t thoroughly investigated.

The case “remains active and is being aggressively investigated,” police said in a statement.

On October 16, 2009, the Tribune reported:

Nobody has heard from Yasmin, and police are aggressively investigating her disappearance. But it wasn’t that way initially, family members allege, and police now admit.

“I think they saw this house, this neighborhood and our color and race,” says Starnes, who is African-American, as is Yasmin. “When black girls disappear, for some reason, they think she ran away with a boy and will come home.”

Starnes says she frantically told responding officers that, “It was plum out of [Yasmin’s] character to run away” and that doors leading from the basement to the alleyway had been forced, and a lock was cut off with bolt cutters.

“They didn’t even look at the door or go downstairs to her room,” Starnes says. During that time, the family and several local pastors tried to publicize the disappearance, prompting police to return to look for fingerprints and evidence, including the lock, she says.

In a rare concession, police admitted in a letter this year that the situation was mishandled.

“All available evidence was evaluated and it has been determined that misconduct on the part of the Department member(s) has been proven,” wrote Juan Rivera, chief of the Internal Affairs Division. The letter to Starnes was in response to a formal complaint she had filed in July 2008 about the initial investigation.

Chicago police spokesman Roderick Drew said officers should have taken the lock. Detectives returned the next day to retrieve it, and the mistake did not impede the investigation, he said.

Seven other stories have appeared in the Tribune since, and we will look at one in particular later.

By contrast, the Sun-Times has only reported on Yasmin twice, according to the ProQuest database, and the first time was on July 8, 2008 – six months after the Tribune’s first report – when columnist Mary Mitchell complained about the media’s alleged disinterest in Yasmin’s case.

Shortly after she vanished, Yasmin was profiled by CLTV, NBC-5 and Fox News.

But the coverage was nothing compared to the media blitz that followed the disappearance of two suburban women last year.

Stacy Peterson, 23, went missing on Oct. 28, in Bolingbrook. At least 150 articles or columns mentioning Peterson have appeared in this newspaper alone.

Before then, the “missing person” spotlight was on a 37-year-old Plainfield woman, Lisa Stebic. She went missing April 30, 2007, and her case also dominated the news.

I don’t disagree with the disparity, but I’d argue that the problem isn’t that Yasmin hasn’t gotten enough attention but that Peterson and Stebic have gotten too much – and while race likely has something to do with it, so does the fact that the Peterson and Stebic cases had dramatic Hollywoodesque elements that, these days, trump journalism values.

Mitchell wrote:

Starnes’ former boyfriend should have been hounded by the media and the police just as the men in the Stebic and Peterson cases were hounded.

Disagree. Our job as journalists isn’t to hound suspects; that’s the job of the police. Our job is to hound the police.

“Frankly, the blatant disparity in how the media handles missing person cases exposes an industrywide bias.”

A longtime truth. Minor crimes in Lincoln Park often get more coverage than major crimes in Englewood. Talk to your editors, Mary. They’re as guilty as the other news managers in this town and around the country. Where does change start, if not from within?

On September 11, 2009, the Sun-Times reported:

The Chicago Police Department has sustained a complaint against two officers in connection with the investigation into the disappearance of a 15-year-old girl, a police source confirmed Thursday.

The department would not officially discuss the nature of the complaint or what punishment the officers might face, if any.

But a source said the complaint was filed by Rose Starnes, an aunt of Yasmin Acree , who was reported missing from the West Side on Jan. 16, 2008.

In her complaint, Starnes said two officers responded to her home in the 4800 block of West Congress to take a missing-person report.

Starnes said she showed them a lock that had been cut off a rear basement door. Yasmin lived in the lower level of the house.

But the officers would not inventory the lock, Starnes said in her complaint.

The family continued to call police about the lock, which Starnes considered evidence in Yasmin ‘s disappearance. On Jan. 17, 2008, the lock was inventoried by police. Starnes filed her complaint Jan. 18, 2008.

The police source said the officers should have inventoried the lock at the time they first responded to the home.

Starnes and a group of ministers gathered outside police headquarters Thursday to announce that the officers were “found guilty of misconduct.”

But police Supt. Jody Weis told reporters that “in no way did these officers’ actions impact the investigation” into Yasmin ‘s disappearance.

By the time of that report, Yasmin’s case had already been on America’s Most Wanted and Nancy Grace.

*

Last March, the Tribune turned in a stellar piece of reporting on Yasmin’s disappearance that illustrates the failures of police as well as the clouded circumstances of the case that make it not as clear-cut as some portrayals make it:

The 2008 disappearance of 15-year-old Yasmin Acree sparked a massive police investigation that sent detectives on hundreds of leads, including false sightings that stretched from her tough West Side neighborhood to Michigan and New York City.

But Tribune reporters recently uncovered a piece of potential evidence that hadn’t been turned up by police: a diary Yasmin hid in her bedroom.

In it, Yasmin twice mentioned a 35-year-old man who had lived for several months in a separate second-floor apartment at her two-flat.

“I miss Tyrell . . . ,” Yasmin wrote.

Yasmin was referring to Jimmie Terrell Smith, who had moved into her building after serving more than 10 years for attempted murder.

Described in court records as a brutal predator, Smith is now in Cook County Jail awaiting trial on charges of raping five females, including two 14-year-olds he is alleged to have kidnapped. Smith had shown an interest in Yasmin and had contact with her after he moved out of her two-flat, including at a family friend’s house shortly before she vanished, according to Tribune interviews.

In three recent jailhouse interviews, Smith told the Tribune he had vital information about Yasmin’s disappearance.

“I know what happened to her,” Smith said, although he did not admit any direct involvement in Yasmin’s vanishing.

Smith claimed he also was responsible for four uncharged homicides. But for now, Smith said, he wasn’t going to say what he knew. “I’d be putting my head in a noose.”

Smith’s statements may be the fabrications of a career criminal facing the possibility of years behind bars, and Yasmin’s diary entries may simply reflect her private teenage fantasies.

But over the last 18 months, detectives have twice brought Smith from jail to question him about Yasmin, including once for more than 30 hours. And earlier this month, based on information uncovered by the Tribune, police obtained a warrant to search a now-empty South Side home where Smith had lived on and off with a girlfriend in 2008 and 2009.

For 90 minutes eight officers moved in and out of the frame house in the rain on the evening of March 4. An evidence photographer’s strobe lit the home from within and officers’ flashlight beams swept the backyard as they combed slowly for evidence amid the downpour. Police left with four evidence bags.

The Tribune’s reporting on Yasmin’s disappearance not only sheds light on Smith’s contacts with her, but adds new dimension to her life and the often-criticized police investigation into the case.

Police failed to uncover potential leads, even beyond the diary discovered by reporters. It took nearly a year and a half for detectives to learn that Smith had lived in the building’s second-floor apartment.

Yasmin’s diary, as well as Tribune interviews with more than a dozen relatives and renters in Yasmin’s two-flat and hundreds of pages of government records, shows the fragile girl was in many ways left unprotected by the adults in her life, including child welfare authorities.

I recommend reading the whole thing. And I recommend the Tribune and other papers not be afraid, as they always have been, of re-running or repeating in various clever (or not) ways important stories that disappear within a day. With the Internet, it makes even more sense. “With the broadcast of Find Our Missing tonight, we thought we’d provide this account from March 2011 for background . . . ”

In the old days, newsrooms have always had a weird bias against re-running stories, as if readers/citizens only get one shot and too bad if they miss it. I always argued there was value, in some cases, of giving folks a second chance to see a story they may have missed. Now on the Internet, stories can have what they call a long tail. But they have to be highlighted to do so effectively.

*

I didn’t review local TV coverage other than seeing some of the references in the articles above.

*

Yasmin’s story appeared last week on channel 172, for those of you with Comcast. The embed provided doesn’t work, but you can watch the show here.

*

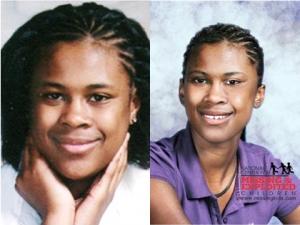

Police have also released this rendering of what Yasmin might look like today:

The family is offering a reward: $5,000 to anyone with information that will help solve the case. Those with information should call 1-800-843-5678.

*

Press release issued Friday from Ira J. Acree via Chinta Strausberg (links added):

Chicago Pastor calls for restoration of FCC law that would help report black missing children

Denounces the disparity in media coverage

Taking his fight for parity in investigating missing black children on a national front, Ira J. Acree, pastor of the Greater St. John Bible Church, a cousin to then 15-year-old Yasmine Rayon Acree missing since January 15, 2008, appeared on ABC’s The View today to discuss the obvious disparity of media coverage between black and white missing children.

He was accompanied by Rose Starnes, the mother of Yasmine who is a cousin to Pastor Acree who later told Challenge News he blames the predominately white-controlled male media for their lack of sensitivity in covering missing black children.

And, he believes it’s time for the restoration of the FCC’s Minority Tax Certificate program that was in existence from 1978-1995 – a program that increased minority ownership of radio and TV stations; that is until it was repealed.

If this program were restored, Acree said there would be the diversity in the newsrooms so when a story like missing Yasmin would come across the wire this could like the other white high profile missing persons would have been covered.

Before going on The View, Acree read reports from The American Society of Newspaper Editors that discussed the disparity in reporting missing black vs. white children. “Initially, were very stunned and shocked by the lack of national attention for Yasmin and other black children, but when we researched it, there are probably reasons behind this,” said Acree.

“The national media is dominated by white males even though the minority population is 28 percent, out of all the newsroom employees, minorities only make up 13 percent and minorities only own 3 percent of TV ownership and 7 percent of radio. We are truly a minority voice,” he reasoned. “I don’t think it may be intentional racism, but it is because of the cultural background of the white males who dominate the industry and their natural comfort zone” that may be the problem.

At that time Yasmin disappeared, Mrs. Starnes said she made out a police report. Acree said they had difficulty only because the initial investigating officer “inaccurately classified Yasmin as a runaway rather than missing.”

And, because of that erroneous classification, Acree said they were unable to get coverage all except the Austin Weekly newspaper which covered a prayer vigil. Acree said Channel 5 came out but explained because the police classified her as a runaway, they couldn’t do much with the story.

That prompted Acree and the mother to file a complaint with Internal Affairs. Ultimately, the runaway classification was dismissed and Yasmine was labeled a missing person; however, that was a year later. In the interim, many “missteps” were made by the police, Acree said pointing out that the first 48-hours after a person is missing are crucial.

Starnes’ home had been broken into that day including the cutting of a lock that was never confiscated by the police. Yasmin’s mother continues to believe her daughter’s abduction was targeted and that the break-in was planned “since the only thing missing” was her youngest child, Yasmin whose bedroom was in the basement.

Like Acree, Starnes said, “I do believe there is a disparity between the investigations of black and white missing children. “You hear a lot in the media, how they are searching for that child but when whites are missing, they do more. There are a lot of black children missing, but we don’t hear anything about it,” said the mother of four.

Acree added, “I think that attributes to these innocent children being put in harms way. We are victimized by the white dominated male media. For a better America, I believe the FCC should come in and restore the FCC’s Minority Tax Certificate Program that allowed cable owners to sell to minority owners to get a tax break. I think that would be very helpful. It would make for a safer and better America for everyone,” said Acree.

“When you have diversity in the media, that would give them incentive” to cover minorities. He said when a child is missing it is critical to let the public know. “If there is more diversity, I think we’ll have a better share of everybody getting a fair share of media exposure. And restoring the FCC Minority Tax Certificate would help the public to have a role in locating missing children,” said Acree.

*

From The View:

*

See also: What’s Missing From Television Coverage Of Missing Persons?

*

And from the American Journalism Review vault:

The City News Bureau of Chicago, which expired March 1 awash in nostalgia, was legendary for its hard-nosed approach, epitomized by the saying: “If your mother says she loves you, check it out.” But there was another, less admirable and more common phrase used 40 years ago that does not reflect as well on the training ground for so many Chicago journalists: “Cheap it out.”

One meaning of this phrase was that a story offered by a rookie reporter did not meet the standard for publication in any of the Chicago newspapers that supported the bureau. But “cheap it out” also had a racial connotation. If a story involved African Americans, the typical response of the desk editors to reporters was to ignore it, or “cheap it out.”

Posted on January 29, 2012