By The Beachwood Excerpt Affairs Desk

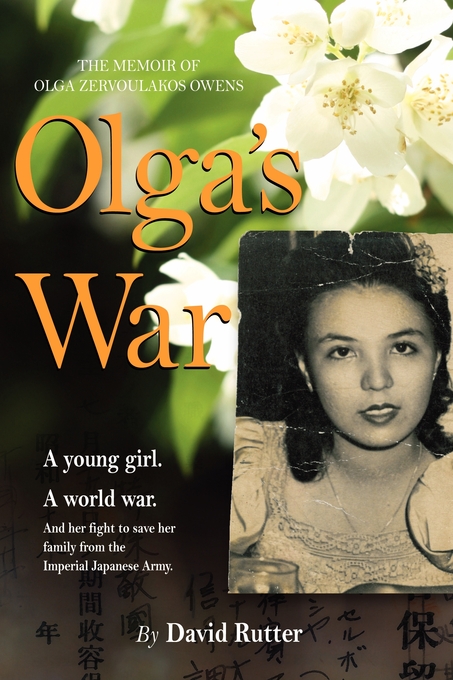

A young girl. A world war. And her fight to save her family from the Imperial Japanese Army. An excerpt from Olga’s War, the new memoir of Olga Zervoulakos Owens, by Beachwood contributor David Rutter.

–

Manila, 1942:

Olga was walking with her family to the market on Wednesday. Upon orders from the Japanese controlling all traffic, their path took them down Vito Cruz Boulevard. And then past the Rizal Memorial Coliseum, one of the jewels of the city. “It was a truly a lovely place,” Olga recalled. “They played baseball and basketball there in the open air and thousands came to see the games. There were these massive trees that ringed the Coliseum in a park.”

But as they walked down the sidewalk past the park that encased the Coliseum grounds in green, Olga peered into the near blackness under the massive acacia tree canopy. And then peered again, straining to see more clearly. Something was there under the tree.

And there. And there. And over there, another. And more.

And then she recognized what she was seeing. They were bodies. They had been strung up over the sturdiest branches of the old trees and been left to hang upside down under the limbs. The long ropes were taut around the legs, and the bodies swung in the breeze. To and fro. Gently, all the while, because the wind was but a whisper.

Who they were or what they had done to deserve this fate was never told. But the Empire had taken issue with their conduct or their attitude. Or perhaps they were merely random examples executed as a civics instruction to others.

Who they were or what they had done to deserve this fate was never told. But the Empire had taken issue with their conduct or their attitude. Or perhaps they were merely random examples executed as a civics instruction to others.

Olga and her stepmother and brothers were shocked into silence. They made the sign of the cross, and prayed silently for the mercy of departed souls.”Hail, Mary, full of grace, the Lord is With Thee ….. and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus,” they all repeated in perfect, silent sorrow. You could not look at the bodies too long for fear your gaze could not turn away.

Stationed near the bodies, Japanese sentries made sure to note the passing crowds with hearty salutations. In turn, the members of the crowd were required to bend low in supplication to indicate they had seen the work of their friends, the Japanese, and knew the implications for each of them if they committed similar sins.

When Japanese soldiers killed civilians, they had little fear of doing so in public. Japanese soldiers almost never were court-martialed for civilian murders. In fact, they seemed to relish the horror it inflicted on others. Besides, only defeated armies need worry about witnesses. Only defeated armies would worry about the judgments of later tribunals, and the Japanese had not been defeated, and fully believed they would never face that event. They had defeated the Chinese, British and Dutch and now they would finish the Americans soon enough.

Killing Filipinos? Who would worry about that?

Then there was the plush golf course down the street from the Coliseum. It had been a favorite of the Americans. PaPa had gone to the club on business, and let Olga come along as a spectator on the first tee. Olga had loved to watch them play and marveled at their gaudy, absurd wardrobes. Now what had been perfectly tended undulating greens were dug up into mini burial plots.

Olga could see heads rising above the shallow graves. Here. There. Over there, several more.

With their bodies laid out in shallow graves, their heads had been left to bleed and boil under the sun. And be consumed by the hungry ants that now swarmed over their faces. They must be dead, Olga thought. Oh, please, God, let them be dead. Let their poor souls be with you, God.

The image of their bloated, distended faces buried on the golf greens shook her down deep. The ghastly memory stayed with her for the rest of her life. She could not make it go from her soul.

The merciless cruelty was not reserved just for civilians. Even before the fall of Bataan and Corregidor, the infamous Bataan Death March in May was preceded by other smaller but no less deadly such marches. Some were American prisoners captured in smaller, more isolated groups; many were Filipino soldiers under MacArthur’s command being marched to unknown prisons. Or more likely to their deaths. Often wounded and hopeless, they straggled down the street with Japanese guards lashing at their heads with rifle butts. It was a hideous spectacle repeated day after day, and the Japanese had no reason to hide their handiwork.

“I saw one soldier stumble because he was dying of thirst,” Olga recalled. “The Japanese guard came up to him and stabbed him in the back with his bayonet.” The soldier lay unmoving. No one moved to see if he might be saved. The Japanese often left them for hours under the bleeding, red sun. The crowds along the streets knew not to react with any sign of sympathy for the victim. Such murders were an object lesson for the living. Manila was learning. Olga was learning.

She had never understood the concept of a mercifully quick death or needed to understand. She was, after all, a child. But in those spring days she came to comprehend what the terror of unimaginable pain might do to a person. And how the fear of it might strip all dignity away from any person’s soul exposed to such relentless brutality. To Olga, it now seemed that there was no need for Satan. Why would God bother with creating a Satan? This scene before her was more evil than the world could tolerate, and it had been made by man.

If the Japanese took me, and that torture had happened to me, how would I stand up to it? she wondered. These people can do almost anything to you and you have no way to resist. I am not courageous. How could I face this? I am afraid to be a coward.

Suddenly, it was clear to her that war was nothing that she had thought it was. Not flags waving and gallant men marching to the airs of patriotic music. She had considered the idea of war to be noble for those fighting in the cause of liberty. And maybe war was necessary when there was no other course to escape it.

But this was also war. Brutal, pointless, cruel death and constant indignity. And there was nothing noble about this and no way to elude the sheer, crushing inhumanity. She could remember no occasion when it had been explained to her that such brutality was as much a part of war as were the stirring, beautiful parades.

The few movies she had ever seen that barely included descriptions of war were nothing like this. The war before her now everyday was not the heroic quest for honor, at all. It was low and mean. It was a horror made even worse by its casual penalty of death.

And now the effect of that reality was much clearer. What a person said and what a person thought could be enough evidence to have a neighbor dragged off into the night never to be seen alive again. Or people tortured and hung upside down to die. Or bayoneted. Or tortures so hideous that one recoiled from the thought of them.

There were civilian rules of conduct now, all listed in the newspaper.

“By this time, we heard the many rumors of them abusing people, torturing people,” Olga said. “If they suspected you for any reason, you were gone. There were many rumors of them coming in the middle of the night. You began to have fear all the time. So many of the things were happening around you all the time.”

Fort Santiago, the ancient fortress built by the Spanish hundreds of years ago and used later as a billet for Americans, took on a dark, fearsome reputation. “That was the place where people were tortured,” Olga said. “The stories were they would pull out fingernails, or put the hose down people’s throats and pour water. ”

But the seeming randomness of the cruelty added power and perversity to its reputation.

“You were always told that if you were walking down the street and a soldier was walking toward you, then you have to stop and bow to them. A lot of people were taken because they didn’t bow.”

More than a small dip of the head was required. A deep, low, ceremonial bend of submission was required. “It didn’t matter if it was an officer or just a private,” she said. “They could just slap you. They announced these rules in the newspaper and on the radio.”

At first, Olga bridled against the regimented indignity but practicality prevailed.

“But then when you see somebody slapped when they didn’t bow and are pulled aside, then you have to make a decision. You don’t want that. So you do what you have to do. They liked to kick you, too. I saw that happen. This was all new to us, but that’s what we had to do to survive.”

Filipinos had blossomed under the American concept of individual liberties, especially those enunciated in the U.S. Constitution. How easily it had been handed to them virtually without it even being asked. And how easily it had disappeared. Those rights now were gone. Freedom was now gone. Stolen from them.

Four days after the occupation began, Angel Zervoulakos reported for interrogation and processing at the Coliseum as the new administrators of the city had commanded in the newspapers.

The Japanese were dispatching foreign suspects into prison camps and the fear such a thing could happen to PaPa frightened Olga beyond reason. But this date with the interrogators had been little more than a bureaucratic once-over. The Japanese were far more interested in finding Americans and their current European allies among the populace. They did not quite know what to make of Zervoulakos, but decided they’d figure out his appropriate station later. He was told not to leave the city and not travel anywhere within the city without good reason. They listed him as a “debt collector” on his ID form but apparently were not aware of his close ties to the Americans. At least not yet.

“What did they ask?” John asked after he returned home.

“Not the right questions,” PaPa replied. “I didn’t have to lie. I just didn’t tell them the full truth.”

And then on Jan. 14, the Japanese took almost more than there was to give, except for the lives of his family.

At 2 a.m., unknown and unexpected visitors were hammering at the front doors with enough force that it seemed to the rudely roused houseboy that the towering, wooden double doors would be knocked off their hinges and be knocked to the floor.

When the door opened into the dark outside, he saw Japanese soldiers. A platoon. They stood ready for combat. They burst through the now open door without conversation and shoved aside the houseboy and knocked him to the floor as they rushed into the foyer. He arose quickly, sought out the large bank of switches and turned on the hallway lights.

The officer at the lead and his soldiers did not speak English and events would reveal the lack to be pointless.

The soldiers hustled smartly throughout the house and roused everyone within it. “A soldier came into my bedroom and when I woke up I could see he was pointing his rifle with the long bayonet at me,” Olga said. “He didn’t speak any English. But he was waving his gun at me, and I could tell I had to get up.”

From their bedrooms on the second floor, and from other quarters at the back of the house, the household came into the light with soldiers nudging them along at the point of their bayonets. PaPa was angry at the indignity but subdued, though almost everyone else was simply petrified.

No one spoke. Olga hovered under her father’s arm for protection and comfort. What was happening? What does it mean? Why are they here?

They were to leave, PaPa knew. Now.

And PaPa could tell that emptying the house of the inhabitants might well mean the family was not coming back here. “We must leave, now,” he told everyone. “Stay together.”

The doors were standing open, and the little band of Zervoulakoses, huddled tightly together, was aimed outside at the point of a bayonet and then expelled. The doors slammed shut behind them.

“From my bed to the door and then outside,” Olga said. “Life as I had known it was completely over.”

And it was done.

–

Buy Olga’s War.

–

Comments welcome.

–

1. From Liz Owens:

Simply amazing.

2. From Les Thomas:

This excerpt gives us a sample of what people went through in an awful time. It is great to have someone who lived it tell the story. I can’t even comprehend what it must have been like for a little girl to witness that level of brutality but the book will give us all the best chance to understand what it was like and by understanding it will enhance our compassion for all people that are persecuted today.

Posted on July 7, 2010