By Steve Yaccino

I was recently jolted from a deep sleep by a surprise 7 a.m. phone call. It was the federal government calling. More specifically, someone from the EPA. It seemed my Freedom of Information Act request was ready. The one I had filed more than three years ago – to track down the yuppie who ratted out the Blommer Chocolate Company. “Do you still want them?” she asked me as if the documents were something she found while cleaning the garage. “Um, yeah.” “Do you still live at the same address?” Since then, I’ve moved five times.

I filed the FOIA request in August 2006 as part of a Beachwood Reporter investigation to uncover the identity of the Fulton River District resident who complained about the smell of chocolate in the air. Since 1939, the neighborhood’s Blommer chocolate factory has pumped its sweet aroma throughout the area and down the capillary avenues that lead to the heart of this city. That smell is a reminder of Chicago’s candy history – the stomping ground for Milk Duds, Tootsie Rolls, Jelly Bellys, and, of course, Wrigley gum. To thousands of workers and residents in the district, the chocolate scent is simply home.

Save one condo dweller. His complaint sparked an EPA citation that found emissions vented from the northeast corner of the factory roof in violation of the 2001 Clean Air Act. To make things right, Blommer would have to install control equipment. Many worried it would also burst the Wonka fantasy.

The citation created uproar in the media at the time. Headlines worldwide – like one India newspaper’s “Sweet Smell No More” – painted the EPA as the malevolent monster, while Blommer made a local PR push to assure neighbors that the substance emitted from its factory was “organic, not toxic.” The only person who evaded the public’s eye was the citizen who complained. And I wanted his story.

While the EPA complied with some portions of our request for all records in the case, they held back the identity of the complaining condo dweller, citing privacy concerns. There was also a list of documents that were not included due to business confidentiality restraints. We wrote our story and moved on.

Until that early morning phone call. Our request was finally being fulfilled. We still don’t know why it took so long. Perhaps the threat to national security has passed.

The new documents are fairly innocuous. They contain mostly records of when various machines were cleaned, repaired, or replaced. According to the EPA Public Information Regulations, a business can file a confidentiality claim if they’re concerned that requested records contain information that would “cause substantial harm to the business’s competitive position,” which can include anything from trade secrets to personal and financial information.

That final determination is made by the EPA, which may ask the business to support its claim before deciding. “There’s a whole process,” an EPA spokesperson told me to justify why the documents took so long. “You have to ask the company to support their designation and then if they don’t give enough information the first time then you have to ask for more.” I was given no further explanation.

But Terry Norton, director of the Center for Open Government at Chicago-Kent College of Law, is baffled about why that process would take three years to complete. He says government agencies usually have administrative rules that put a time limit on their response, though I could find no such clause in the EPA regulations. “I can see where it could get messy if the government did disclose something and there were lawsuits because it helped a competitor, but three years sounds like an excessive amount of time no matter how you cut it,” he says. “It should never get close to that.”

The new documents arrived just weeks before the death of Joe Blommer, the former factory owner and son of its founder. During the 1980s, Joe Blommer expanded the company into the largest cocoa bean processor in North America. His son, Rick, now runs the firm and was there in 2005 when EPA investigators delivered news of the violation and conducted a formal inspection of the facility, records show.

Simply put, the documents provide vivid detail of how one disgruntled neighbor and classic government bureaucracy wasted a lot of people’s time, all chronicled with an anal-retentiveness one would only expect from big city inspectors.

Those EPA investigators were already wearing hairnets when they confronted Blommer to explain their unannounced factory visit on September 23, 2005. It was just after 9:30 a.m., and their agenda over the next six hours would include a impromptu presentation by the owner and his staff about the factory production process followed by a full facility tour and a file review of record logs – pulled undoubtedly by Blommer’s poor secretary.

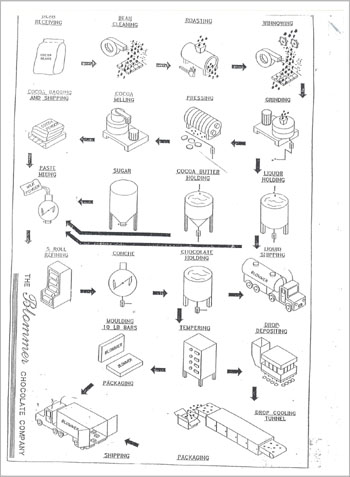

They learned how the facility received some 400,000 pounds of cocoa beans a day from around the world, by truck and rail, and how they were weighed and carried into the building by a vibrating conveyor belt, cleaned and sent through two “classifiers” that removed debris. As he talked, Blommer described the size and installation date of each machine he mentioned. Two roasters located on the fourth floor of the factory were identical, installed in 2003, and could roast up to 8,000 pounds at a time. Ten beater mills spun blades that pulverized the cocoa beans, and ten ball mills used bearings to smash the nib so the chocolate liquor flowed out through a filter screen to be stored, mixed, molded, and eventually shipped. By the time the group finished their opening conference, it was almost noon.

Exactly what, if any, trade secrets Mr. Blommer was worried about divulging as he led the EPA inspectors through the facility is unclear. They started at the loading dock, where earlier that morning investigators had noticed a Blommer employee pounding a filter on the ground that sprayed brown particles into the air. The group eventually climbed a staircase to the roof, then up a ladder to the top of its sugar silos. From where they stood, they could see several stacks scattered on the roof. The ones that lead to the boiler room gave off a colorless vapor that blurred their vision. White emissions plumed from two roaster stacks to the north. A strong odor enveloped them and one inspector “thought it smelled like chocolate.”

From the northeast corner, where the violation had been observed, they could see visible particles blowing out from vents over the railroad tracks that hug the building. But the grinding unit that led to these vents was already scheduled to be replaced the following month, they discovered. In fact, Blommer had submitted a permit application to the Illinois EPA for the new unit installation before the violation was recorded and had been working with the Chicago Department of Environment for the past two years trying to address citizen concerns about odor and emissions, the report explains. By the time the investigators left the facility, it was after 3:30 p.m.

In some ways, nothing has changed. The EPA issued no fine or even agreement that Blommer had committed wrongdoing. The factory installed its emissions control equipment as planned and is in compliance today. For now, Chicago’s bridges still make me crave dessert, its river still circulates the sugary musk past condos and crannied streets. But that smell also carries a bitter dash of inevitability, a reminder of how fragile simple pleasures can be.

Wherever these documents have spent the last three years, it’s the same place where yuppies get cached safe from scrutiny, where government agencies fail to share information, where a city’s arteries slowly clog citation by citation. It is one place I hope never smells like chocolate.

–

Our favorite document finally released from the EPA’s secret vaults:

–

Comments welcome.

Posted on March 1, 2010