By The Center for the Study of the Public Domain

On January 1, works from 1924 will enter the U.S. public domain1, where they will be free for all to use and build upon, without permission or fee.

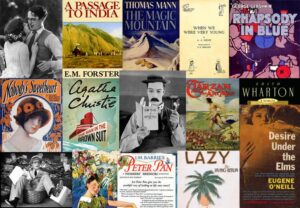

These works include George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, silent films by Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd, and books such as Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India, and A. A. Milne’s When We Were Very Young.

These works were supposed to go into the public domain in 2000, after being copyrighted for 75 years. But before this could happen, Congress hit a 20-year pause button and extended their copyright term to 95 years2. Now the wait is over.

How will people celebrate this trove of cultural material?

* The Internet Archive will add books, movies, music, and more to its online library.

* HathiTrust will make tens of thousands of titles from 1924 available in its digital library.

* Google Books will offer the full text of books from that year, instead of showing only snippet views or authorized previews.

Community theaters can screen the films. Youth orchestras can afford to publicly perform the music. Educators and historians can share the full cultural record. Creators can legally build on the past – reimagining the books, making them into films, adapting the songs

Here are some of the works that will be entering the public domain in 2020. (To find more material from 1924, you can visit the Catalogue of Copyright Entries.) A fuller (but still partial) listing of over a thousand works that we have researched can be found here. (You can click on some of the titles below to get the newly public domain works.)

Films

- Buster Keaton’s The Navigator

- Harold Lloyd’s Girl Shy and Hot Water

- The first film adaptation of Peter Pan3

- The Sea Hawk

- Secrets

- He Who Gets Slapped

- Dante’s Inferno

Books

- Thomas Mann, The Magic Mountain

- E.M. Forster, A Passage to India

- Ford Madox Ford, Some Do Not… (The first volume of his Parade’s End tetralogy)

- Eugene O’Neill, Desire Under the Elms

- Edith Wharton, Old New York (four novellas)

- Yevgeny Zamyatin, We (the English translation by Gregory Zilboorg)

- A.A. Milne, When We Were Very Young

- Hugh Lofting, Doctor Dolittle’s Circus

- Edgar Rice Burroughs, Tarzan and the Ant Men

- Agatha Christie, The Man in the Brown Suit

- Lord Dunsany (Edward Plunkett), The King of Elf’s Daughter

Music

- Rhapsody in Blue, George Gershwin

- Fascinating Rhythm and Oh, Lady Be Good, music George Gershwin, lyrics Ira Gershwin

- Lazy, Irving Berlin

- Jealous Hearted Blues, Cora “Lovie” Austin (composer, pianist, bandleader) (recorded by Ma Rainey)

- Santa Claus Blues, Charley Straight and Gus Kahn (recorded by Louis Armstrong)

- Nobody’s Sweetheart, music Billy Meyers and Elmer Schoebel, lyrics Gus Kahn and Ernie Erdman

(Only the musical compositions referred to above are entering the public domain. Particular recordings of those compositions, such as Yuja Wang’s performance of Rhapsody in Blue, might still be copyrighted. You are free to copy, perform, record, or adapt Gershwin’s composition, but may need permission to use a specific recording of it.)4

Why celebrate the public domain?

A wellspring for creativity. The goal of copyright is to promote creativity, and the public domain plays a central role in doing so. Copyright law gives authors important rights that encourage creativity and distribution. But it also ensures that those rights last for a “limited time” so that when they expire, works can go into the public domain, where future authors can legally build upon their inspirations. As explained by the Supreme Court:

[Copyright] is intended to motivate the creative activity of authors and inventors by the provision of special reward, and to allow the public access to the products of their genius after the limited period of exclusive control has expired. Sony v. Universal (1984).

Several of the works above were based on public domain works. Eugene O’Neill’s Desire Under the Elms adapted Greek myths to a rural New England setting. Dante’s Inferno fused parts of Dante’s Divine Comedy with elements from Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. In 2020, anyone can use these works as raw material for their own creations, without fear of a lawsuit.

Access to our cultural heritage. The public domain also enables access to cultural materials that might otherwise be lost to history. 1924 was a long time ago. The vast majority of works from 1924 are out of circulation. When they enter the public domain in 2020, anyone can make them available online, where we can discover, enjoy, and breathe new life into them. (Empirical studies have shown that public domain books are less expensive, available in more editions and formats, and more likely to be in print – see here, here, and here.)

The works listed above are famous, that is why we included them. But they are just the tip of the iceberg. Who knows what forgotten works you might find?

In 2019, works from 1923 went into the public domain and came online. This allowed enthusiast Parker Higgins to create 1923: A monthly zine of public domain treasures, where he unearths and shares everything from costume drawings from the legendary Hippodrome theater to illustrations of birds, to journals from a group of Mexican futurists known as “los estridentistas.”

Images from 1923: A monthly zine of public domain treasure

Images from 1923: A monthly zine of public domain treasure

It also inspired Techdirt’s Gaming Like It’s 1923, a contest inviting the public to create games based on the newly public domain works.

Unfortunately, the fact that works from 1924 are legally available does not mean they are actually available. After 95 years, many of these works are already lost or literally disintegrating (as with old films5 and recordings), evidence of what long copyright terms do to the conservation of cultural artifacts.

In fact, one of the items we feature below, Clark Gable’s debut in White Man, apparently no longer exists.

For the works that have survived, however, their long-awaited entry into the public domain is still something to celebrate.

(Under the 56-year copyright term that existed until 1978, we would really have something to celebrate – works from 1963 would be entering the public domain in 2020!)

Rhapsody in Blue . . . Now Open for You!6

The law that expanded the copyright term is sometimes referred to as the “Mickey Mouse Protection Act,” because it was supported by Disney in an effort to prevent the short film Steamboat Willie, Mickey Mouse’s screen debut, from going into the public domain. (The film will now be in the public domain in 2024.)

But it was not just Disney that lobbied for the extra 20 years. The Gershwin Family Trust also pushed for the extension, so that George and Ira Gershwin’s works from the 1920s and 1930s would remain under copyright.

The Gershwin Trust’s goal was not only to continue receiving royalties, but also to exert creative control. As Marc Gershwin explained:

The monetary part is important, but if works of art are in the public domain, you can take them and do whatever you want with them. For instance, we’ve always licensed Porgy and Bessfor stage performances only with a black cast and chorus. That could be debased. Or someone could turn Porgy and Bess into rap music.

(In response to the concern about rap music, Steve Zeitlin wrote in a New York Times Op-Ed, “The work of the Gershwin brothers drew on African-American musical traditions. What could be more appropriate?”)

Sometimes this creative control takes the form of restrictions on new uses: the estate presided over a Broadway-friendly version of Porgy and Bess encouraging the director to make controversial changes including a more upbeat ending and new dialog. Other times the estate simply exercises a veto: for example, it stopped a British clergyman from rewriting the song “Summertime” because “his lyrics were terrible.”

After 95 years of exclusivity, Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue is now entering the public domain, where it will be freely available to the next Gershwin, even if he is a rap artist, or his lyrics are “terrible.”

As explained in a 1998 New York Times editorial:

When [then-U.S. Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-UT)] laments that George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue will soon “fall into the public domain,” he makes the public domain sound like a dark abyss where songs go, never to be heard again. In fact, when a work enters the public domain it means the public can afford to use it freely, to give it new currency . . . [works in the public domain] are an essential part of every artist’s sustenance, of every person’s sustenance.

Perhaps Shakespeare’s heirs would not have approved of 10 Things I Hate About You or Kiss Me Kate (derived from The Taming of the Shrew), or West Side Story or Romeo Must Die (from Romeo and Juliet). But the ability to freely reimagine Shakespeare’s works has spurred a vast amount of creativity, from the serious to the whimsical, and allowed his legacy to endure.

Of course, it is entirely understandable that the Gershwin Trust would want 20 more years of copyright. Gershwin’s music had enduring popularity, and was still earning royalties. But when Congress extended the copyright term for Gershwin, it also did so for all of the works whose commercial viability had long subsided.

Unlike the Gershwin Trust, no one benefitted from continued copyright. Yet those works – probably 99% of the material from 1924 – remained off limits, for no good reason.

(A Congressional Research Service report indicated that only around 2% of copyrights between 55 and 75 years old retain commercial value. After 75 years, that percentage is even lower. Most older works are “orphan works,” where the copyright owner cannot be found at all.)

George Gershwin said of Rhapsody in Blue: “I heard it as a sort of musical kaleidoscope of America, of our vast melting pot, of our unduplicated national pep, of our blues, our metropolitan madness.”

Indeed, Rhapsody is a musical melting pot: it draws on everything from African-American blues, jazz, and ragtime styles, to French impressionists and European art music, to Jewish musical traditions, to Tin Pan Alley. Now that it is in the public domain, this wonderful composition can be part of your kaleidoscope, where you can draw upon it to create something new, just as Gershwin drew upon his influences.

More Works!

Technically, many works from 1924 may already be in the public domain because the copyright owners did not comply with the “formalities” that used to be necessary for copyright protection.7 Back then, your work went into the public domain if you did not include a copyright notice – e.g. “Copyright 1924 Edith Wharton” – when publishing it, or if you did not renew the copyright after 28 years.

Current copyright law no longer has these requirements. But, even though those works might technically be in the public domain, as a practical matter the public often has to assume they’re still copyrighted (or risk a lawsuit) because the relevant copyright information is difficult to find – older records can be fragmentary, confused, or lost.

That’s why Public Domain Day is so significant. On January 1, the public will know that works published in 1924 are free for use without tedious or inconclusive research.

In an abundance of caution, our lists above only include works where we were able to track down the renewal data suggesting that they are still in copyright through the end of 2019, and affirmatively entering the public domain in 2020. However, there were many exciting works from 1924 for which we could not locate renewals. They will also be in the public domain in 2020, but may have entered the public domain decades ago due to lack of renewal. Here are some of those works.

- W. E. B. Du Bois, The Gift of Black Folk

- Pablo Neruda, Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair

- Jelly Roll Morton, King Porter Stomp

- Gertrude “Ma” Rainey (“Mother of the Blues”), Counting the Blues

- It had To Be You (music Isham Jones, lyrics Gus Kahn)

- Everybody Loves My Baby, but My Baby Don’t Love Nobody but Me (music Spencer Williams, lyrics Jack Palmer)

- The Thief of Bagdad

- Greed

- White Man (Clark Gable’s film debut)

It’s a Wonderful Public Domain . . . What happens when works enter the public domain? Sometimes, wonderful things. The 1947 film It’s A Wonderful Life entered the public domain in 1975 because its copyright was not properly renewed after the first 28-year term. The film had been a flop on release, but thanks to its public domain status, it became a holiday classic.

Why? Because TV networks were free to show it over and over again during the holidays, making the film immensely popular.

But then copyright law reentered the picture. In 1993, the film’s original copyright holder, capitalizing on a recent Supreme Court case, reasserted copyright based on its ownership of the film’s musical score and the short story on which the film was based (the film itself is still in the public domain). Ironically, a film that only became a success because of its public domain status was pulled back into copyright.

What Could Have Been

Works from 1924 are finally entering the public domain, after a 95-year copyright term. However, under the laws that were in effect until 1978, thousands of works from 1963 would be entering the public domain this year. They range from the books The Fire Next Time and Where the Wild Things Are, to the film The Birds and the album The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, and much more. Have a look at some of the others.

In fact, since copyright used to come in renewable terms of 28 years, and 85% of authors did not renew, 85% of the works from 1991 might be entering the public domain!

Imagine what the great libraries of the world – or just internet hobbyists – could do: digitizing those holdings, making them available for education and research, for pleasure and for creative reuse.

Want to learn more about the public domain? Here is the legal background on how we got our current copyright terms (including summaries of recent court cases), why the public domain matters, and answers to Frequently Asked Questions.

You can also read James Boyle’s book The Public Domain: Enclosing the Commons of the Mind (Yale University Press, 2008) – naturally, you can read the full text of The Public Domain online at no cost and you are free to copy and redistribute it for non-commercial purposes.

You can also read “In Ambiguous Battle: The Promise (and Pathos) of Public Domain Day,” an article by Center Director Jennifer Jenkins revealing the promise and the limits of various attempts to reverse the erosion of the public domain, and a short article in the Huffington Post celebrating a previous Public Domain Day.

1 In 2019, published works entered the U.S. public domain for the first time since 1998. However, in the interim, a small subset of works – unpublished works that were not registered with the Copyright Office before 1978 – had been entering the public domain after a “life plus 70” copyright term. But, because these works were never published, potential users are much less likely to encounter them. In addition, it is difficult to determine whether works were “published” for copyright purposes. Therefore, this site focuses on the thousands of published works that are finally entering the public domain. Please note that unpublished works that were properly registered with the Copyright Office in 1924 are also entering the public domain after a 20 year wait – for those works, copyright was secured on the date of registration.

2 The 1998 Copyright Term Extension Act gave works published from 1923 through 1977 a 95-year term. They enter the public domain on January 1 after the conclusion of the 95th year. Works published from 1923-1977 had to meet certain requirements to be eligible for the 95-year term – they all had to be published with a copyright notice, and works from 1923 – 1963 also had to have their copyrights renewed after the initial 28-year term. Foreign works from 1924 are still copyrighted in the U.S. until 2020 if 1) they complied with U.S. notice and renewal formalities, 2) they were published in the U.S. within 30 days of publication abroad, or 3) if neither of these are true, they were still copyrighted in their home country as of 1/1/96. Note that the copyright term for older works is different in other countries: in the EU, works from authors who died in 1949 will go into the public domain in 2020 after a life plus 70-year term, and in Canada, works of authors who died in 1969 will enter the public domain after a life plus 50-year term.

3 Fun fact: in the UK, the Peter Pan play and novel are subject to an unusual piece of legislation that gives the Great Ormond Street Hospital perpetual royalties from their use (just royalties, not creative control). You can read more about Peter Pan and copyright here.

4 The list of public domain music refers to the “musical composition” – the underlying music and lyrics – not the sound recordings of those compositions. Federal copyright did not used to cover sound recordings from before 1972 (though pre-1972 sound recordings were protected under some states’ laws). However, a new law from 2018 called the Music Modernization Act (“MMA”) has federalized copyright for pre-1972 sound recordings, in order to clear up the confusing patchwork of state law protection. Recordings from 1924 will enter the public domain in 2025. Importantly however, unlike the rest of copyright law, the MMA allows for uses of orphan works: if those older recordings are not being commercially exploited, there is a process for lawfully engaging in noncommercial uses. For more information about this law, please see the Copyright Office’s summary. While musical compositions are still copyrighted, there is a “compulsory license” that allows people to make recordings if they pay a standard royalty and comply with the license terms. However, this compulsory license doesn’t cover printing sheet music, making public performances, synchronizing audio with video, or making “derivative works.” And, of course, it requires payment. Public domain compositions can be freely recorded.

5 Many silent films were intentionally destroyed by the studios because they no longer had apparent value. Other older films have disintegrated while preservationists waited for them to enter the public domain, so that they could legally digitize them. (There is a narrow provision allowing some restorations, but it is extremely limited.) The Librarian of Congress estimates that more than 80% of films from the 1920s has already decayed beyond repair. Endangered film footage includes not only studio productions, but also works of historical value, such as newsreels, anthropological and regional films, rare footage documenting daily life for ethnic minorities, and advertising and corporate shorts. (For more information, see here.)

6 Here are some resources for this section. Several New York Times editorials expressing concern about term extension discussed the Gershwin estate’s lobbying efforts. See Keeping Copyright in Balance, (February 21, 1998), Dinitia Smith, Immortal Words, Immortal Royalties? Even Mickey Mouse Joins the Fray (March 28, 1998), and Steve Zeitlin, Strangling Culture With a Copyright Law (April 25, 1998). Sources about the Gershwins’s royalties and creative control include NPR, Managing the Gershwins’ Lucrative Musical Legacy and John J. Fialka, Songwriters’ Heirs Mourn Copyright Loss, the Wall Street Journal (Oct. 30, 1997) (“A nationwide license for a Gershwin song that would have fetched $45,000 to $75,000 15 years ago . . . now goes for between $200,000 and $250,000.”). Additional resources about musical borrowing by the Gershwins include Olufunmilayo B. Arewa, Copyright on Catfish Row: Musical Borrowing, Porgy and Bess, and Unfair Use, 37 Rutgers L.J. 277 (2006); David Schiff, Gershwin: Rhapsody in Blue (1997); and The True Origins of Gershwin’s “Summertime”.

7 Millions of books published from 1925 – 1963 are actually in the public domain because the copyright owners did not renew the rights. Efforts are underway to unlock this “secret” public domain, but compiling a definitive list of those titles is a daunting task. The relevant registration and renewal information is in the 450,000-page Catalog of Copyright Entries (“CCE”). Currently, there is no way to reliably search the entire CCE, but thankfully the New York Public Library is in the midst of converting the CCE into a machine-searchable format. Even after this is complete, however, confirming that works without apparent renewals are in the public domain involves additional complexities. As of September 2019, the HathiTrust Copyright Review Program has completed this process with 506,989 U.S. publications, and determined that 302,915 (59.7%) are in the public domain, and can therefore be made available online. The work of the New York Public Library, HathiTrust, and other groups continues, with the goal of opening these public domain books to the public.

Special thanks to our tireless and talented research maven and website guru Balfour Smith for building this site and compiling the list of works from 1924.

Public Domain Day 2020 by Duke Law School’s Center for the Study of the Public Domain is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Public Domain Day 2020 by Duke Law School’s Center for the Study of the Public Domain is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

–

Comments welcome.

Posted on January 1, 2020