By Darío Fernández-Bellon/The Conversation

Expectations are high for the BBC’s new series Seven Worlds, One Planet, but do nature documentaries do enough for the environment?

The BBC and David Attenborough have been criticized for side-stepping environmental issues and portraying the natural world as a pristine wilderness in their shows.

Even the recent Netflix series Our Planet – which went further to highlight climate change, habitat loss and species extinctions – shied away from depicting the true scale of these problems, according to some viewers.

EPA, Joe Castro

EPA, Joe Castro

Natural history TV producers, including Attenborough, have insisted that alarmism is a turn-off for audiences. But on both sides, the debate seems to be largely based on impressions of how audiences behave, rather than on evidence of how audiences react to these shows.

I wondered about this as I watched Planet Earth II in late 2016. I saw that the hashtag #PlanetEarth2 was trending on social media every time an episode was broadcast, and I realized that there may be a way to measure how these documentaries affect people.

Our research, published in Conservation Letters, analyzed data from Twitter and Wikipedia to understand how people behave after watching nature documentaries.

Planet Earth II barely mentioned environmental issues – only 6% of the script was dedicated to topics like climate change, and audiences reacted accordingly. Analyzing 30,000 tweets with the hashtag #PlanetEarth2 that were posted during episode broadcasts, we saw that only 1% mentioned topics such as species extinction or other environmental issues.

Although the show lacked a clear conservation message, we wondered whether it could still influence audience perceptions of nature, so we looked at the species featured in Planet Earth II. Mammals were hugely overrepresented relative to their diversity in the wild, at the expense of invertebrates, fish, amphibians and reptiles. More than half the series was dedicated to mammals, although they are thought to account for less than 4% of all animal species.

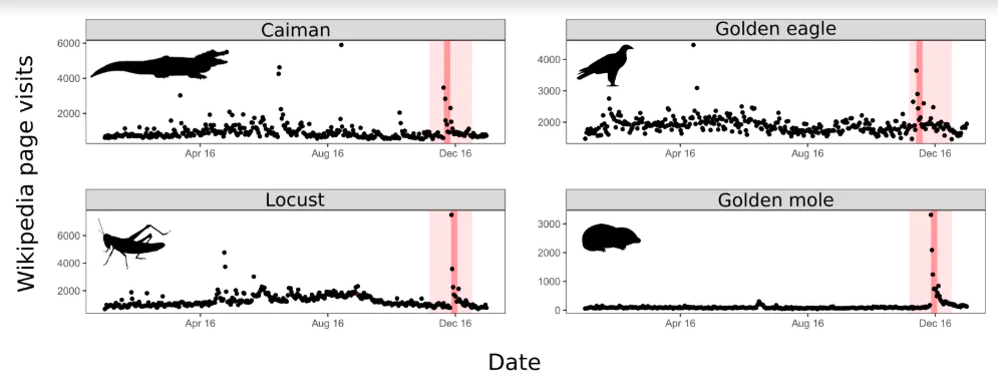

Well-known species recorded peaks on Wikipedia pages after Planet Earth II, but this effect was more noticeable for less-known species. Red bar: broadcast of the episode with featured species. Red band: broadcast of the entire series/Darío Fernández-Bellon

Well-known species recorded peaks on Wikipedia pages after Planet Earth II, but this effect was more noticeable for less-known species. Red bar: broadcast of the episode with featured species. Red band: broadcast of the entire series/Darío Fernández-Bellon

Surprisingly, audience reactions on Twitter did not reflect the “charismatic mammal” bias. Whether people tweeted about a species in the show had nothing to do with what taxonomic group it belonged to. The animals that got the biggest reactions weren’t the most endangered either – they were simply those that got the most time on screen. Locusts actually received more Twitter attention than the giraffe-hunting lions.

The Twitter data showed that audiences reacted to the species featured in nature documentaries, but in unexpected ways. Analyzing Wikipedia activity, we found that almost half of the Planet Earth II species registered annual peaks in visits to their Wikipedia pages immediately after the show was broadcast. People were searching for information on the animals they had just seen and again, the species that got the most airtime also got the most visits on Wikipedia. Those same species still had higher page visit rates up to six months after the show than they did before.

In fact, Planet Earth II even served to put some species on the map. Animals like the golden mole received little or no attention before the broadcast, but their Wikipedia pages were regularly visited after Planet Earth II. Galapagos racer snakes – made famous by the scene in which they chased an iguana – had no Wikipedia page before the show, but one was created only two days after the episode broadcast.

While we had shown how nature documentaries can raise public interest and awareness for different species, we wondered how this compared to other conservation efforts.

If you use social media, you’ll sometimes notice trending topics announcing international days dedicated to a particular species. For instance, February 16 2019 was World Pangolin Day – the scaly mammal that’s the most trafficked animal in the world.

These campaigns are led by conservation organizations and work similarly to nature documentaries – they’re in the public eye for a day and generate huge peaks in online activity. We found that peaks in Wikipedia activity around these international awareness campaigns was similar to those we observed after episodes of Planet Earth II. In other words, the documentary appeared to be as effective in generating interest and awareness as targeted conservation campaigns.

We got in touch with two wildlife charities to see whether they had registered increased donations after Planet Earth II. Sadly, there was no clear link between the documentary and donations, but this isn’t altogether surprising. Donations tend to be influenced by many different aspects, including education and personal attitudes, making it difficult to track them back to specific events.

But our research does show that nature documentaries can make a difference – even those that don’t appear to be overtly conservation-focused. Documentaries can help raise interest and awareness in nature, helping connect increasingly urbanized societies to the natural world. There is scope for these shows to do more though. Even super-productions like Planet Earth II, Our Planet or Seven Worlds, One Planet can help conservation efforts. Simply by giving more screen time to threatened species, they can help raise public awareness and engagement.

Darío Fernández-Bellon is a post-doctoral researcher at the University College Cork This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

–

Click here to subscribe to The Conversation’s climate action newsletter. Climate change is inevitable. Our response to it isn’t.

–

See also: David Attenborough Is Still Betraying The Living World He Loves.

–

Comments welcome.

Posted on October 28, 2019