By Kristin Seefeldt/The Conversation

After “Rose” lost her low-wage job in a Southeast Michigan nursing home, the single mother of four sought Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) benefits.

People who are eligible for this federal, time-limited welfare program for very low-income families must be working or looking for work, a feature the Trump administration and other politicians want to spread to Medicaid and other similar programs that support low-income Americans.

Rose obtained the benefits but lost them after finding that the program was doing little to help her get a job and interfering with her parenting. This fairly common experience suggests that these restrictions can prolong and worsen spells of poverty. Like many experts on American poverty relief, I don’t see why that punitive strategy makes sense.

Work Requirements

When Rose told me her story while I was researching what happens to women like her, she started by saying, “I’m ashamed.” But it sounded like she wasn’t to blame. She was embarrassed about how she had lost her job, but her explanation showed just how tough a spot she had been in.

After working double shifts for a week straight and completing her duties on a Friday night at about 2:30 a.m., “I dozed off. Me and a coworker,” she said. “It’s documented that it wasn’t even 20 minutes that we had dozed off, and a supervisor walked in. We were suspended at that time.” She got fired shortly thereafter.

Rose enrolled in a local job search program. Some of these programs sent participants on job interviews, but Rose, like many of the 22 women I interviewed, said few got hired. The program wanted her to return to the training site after interviews at the end of the day.

“By that time, the kids are getting out of school. You’ve got to get back home, or you’ve got to go pick the kids up from daycare, and I thought that was pointless to do that,” Rose recounted. “If you didn’t come back, you were considered ‘noncompliant,’ so you’d be cut off just like that.”

After months without securing a job and struggling to pick her children up from school on time, Rose opted for the noncompliant label. This meant losing $440 a month in TANF payments, her only source of cash income until, six months later and through her own efforts, she found another low-paying job in a different nursing home. During those six months, Rose sometimes couldn’t afford diapers, which meant her youngest child sometimes went without them. When she ran out of food a couple of times, she would send her children to relatives to eat while she went hungry.

Rose’s experience illustrates the downsides of inflexible work requirements. Instead of getting help finding a new job during those six months, she joined the swelling ranks of families with no cash from welfare or jobs, some of whom wind up scraping by on incomes of $2 a day or less – a common metric for poverty in developing countries. Typically headed by single mothers, these families are cut off from or otherwise unable to access welfare while also having no earnings.

Harsh Labor Market

Working on a team with researchers from the Urban Institute, an independent think tank, I found that almost two-thirds of the mothers we interviewed were able to rely upon partners or family members for help.

Yet this can strain the resources of people who are not much better off than them.

Some may lose housing, which leads them to double up with friends, send children to live with relatives or stay in shelters.

Although more research is needed before we know whether lacking access to welfare makes poor families prone to homelessness, families living in extreme poverty are nearly twice as likely to report housing instability as other low-income families.

You could say that Rose was reaping the consequences of bad choices because she broke a rule. But as I argue in Abandoned Families, my book about the economic and political changes that have thwarted opportunities for upward mobility, the low-wage labor market is harsh.

National data on workplace conditions are scarce, but studies of cities and certain occupations have found that unsafe workplace conditions, irregular and unpredictable scheduling, and wage theft are common.

For example, more than 30 percent of low-wage workers in Syracuse told researchers that their jobs caused a health problem.

Many of the women I profiled in Abandoned Families told me they worked for employers who violated their rights, and mistakes were greeted with threats of or actual termination.

Should Rose have made arrangements for afterschool care for her children? Perhaps, but it’s not fair to presume that this was a viable option for her.

The demand for care after classes end for the day far outstrips its availability: An estimated 18.5 million more children would be in such programs were they available in their community.

Yet funding to help low-income parents pay for it is declining. The federal government spent $11.3 billion on child care in 2014, down from $12.9 billion in 2011.

A Poor Model

The frustrating experiences of women like Rose should make policymakers pause before considering extending work requirements to other programs serving low-income families.

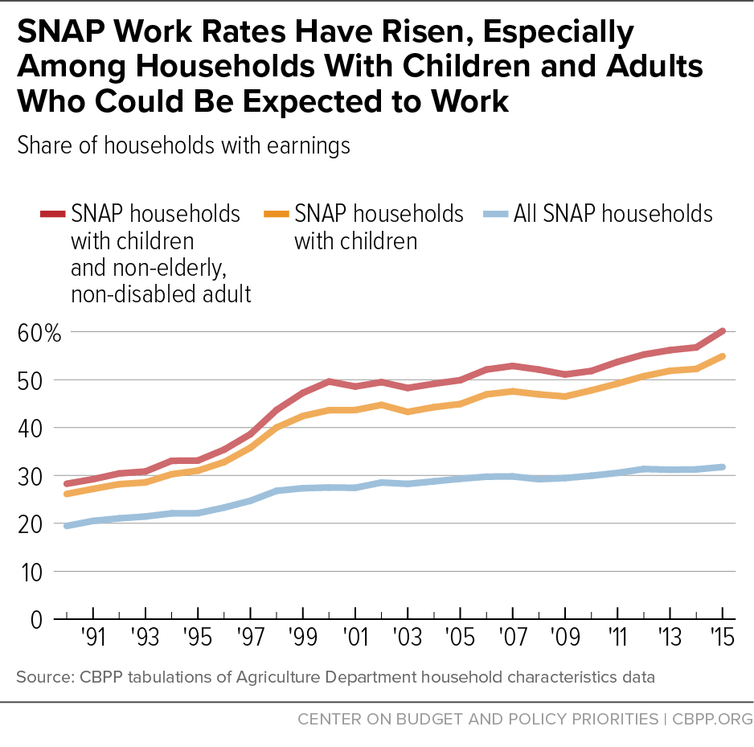

Consider the situation with SNAP, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program more widely known by its pre-2008 name, food stamps. More than 60 percent of the households getting SNAP benefits that have children and what budget director Mick Mulvaney likes to call “able-bodied” adults have at least one employed member.

Others are led by working-class people who are hunting for a new job.

About one-third of all households with SNAP nutritional benefits earn at least some money from work, according to the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, a think tank.

My study showed that work requirements don’t always help people find jobs. Ultimately, the penalties imposed for failure to meet these rules can wind up punishing low-income kids and prolonging hard times.

My study showed that work requirements don’t always help people find jobs. Ultimately, the penalties imposed for failure to meet these rules can wind up punishing low-income kids and prolonging hard times.

Kristin Seefeldt is an assistant professor of social work in the School of Social Work and an assistant professor of public policy in the Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy at the University of Michigan. This article was originally published on The Conversation.

–

Comments welcome.

![]()

Posted on August 3, 2017