By Tobin Miller Shearer/The Conversation

New York City’s Fresh Air Fund has sent city kids, most of them low-income, to suburban and rural neighborhoods for two-week summer vacations for the past 140 years.

Originally intended to restore malnourished, sickly and white immigrant children to health, the fund expanded its mission in the 1960s to focus on – as director Frederick Lewis put it in 1969 – “bridge-building and unifying” across racial lines.

While studying the history of the Fresh Air Fund and more than 60 similar programs across North America between 1939 and 1979, I found a significant gap between their racial aims and what the kids who took part experienced. My new book, Two Weeks Every Summer, examines the experiences of African-American and Latino children who traveled in those years from cities like New York, Chicago and Philadelphia throughout the Northeast and Midwest and to points as far West as Hawaii to stay with host families.

Fresh Air host Mark Stucky of Newton, Kansas, shook hands with Thomas Flowers from Gulfport, Mississippi, as Doris Zerger Stucky – Mark’s mother – watched in this 1960 photo/Mennonite Library & Archives, Bethel, Kansas

Fresh Air host Mark Stucky of Newton, Kansas, shook hands with Thomas Flowers from Gulfport, Mississippi, as Doris Zerger Stucky – Mark’s mother – watched in this 1960 photo/Mennonite Library & Archives, Bethel, Kansas

Nearly all these “guests” encountered bigotry or racial naivete. Since many well-intentioned responses to racially charged violence and rhetoric still follow the same assumptions as those of the Fresh Air movement, it’s important to spot the model’s flaws.

A Long History

Willard Parsons, a Presbyterian minister bent on saving “little tenement prisoners” from the Big Apple’s “squalid homes and sun-baked streets,” founded the Fresh Air Fund in 1877. His interest in immersing city children in the “pastoral peace” found in nature presaged concerns voiced by Richard Louv and others about urban children’s “nature deficit.”

Beginning in the 1950s, as the civil rights movement heated up, the kids taking these trips became more diverse, and more than 80 percent were black or Latino by the late 1970s. Fresh Air programs operated in 20 states by that point, sending children from more than 35 cities on vacation. They had served more than 1.5 million children.

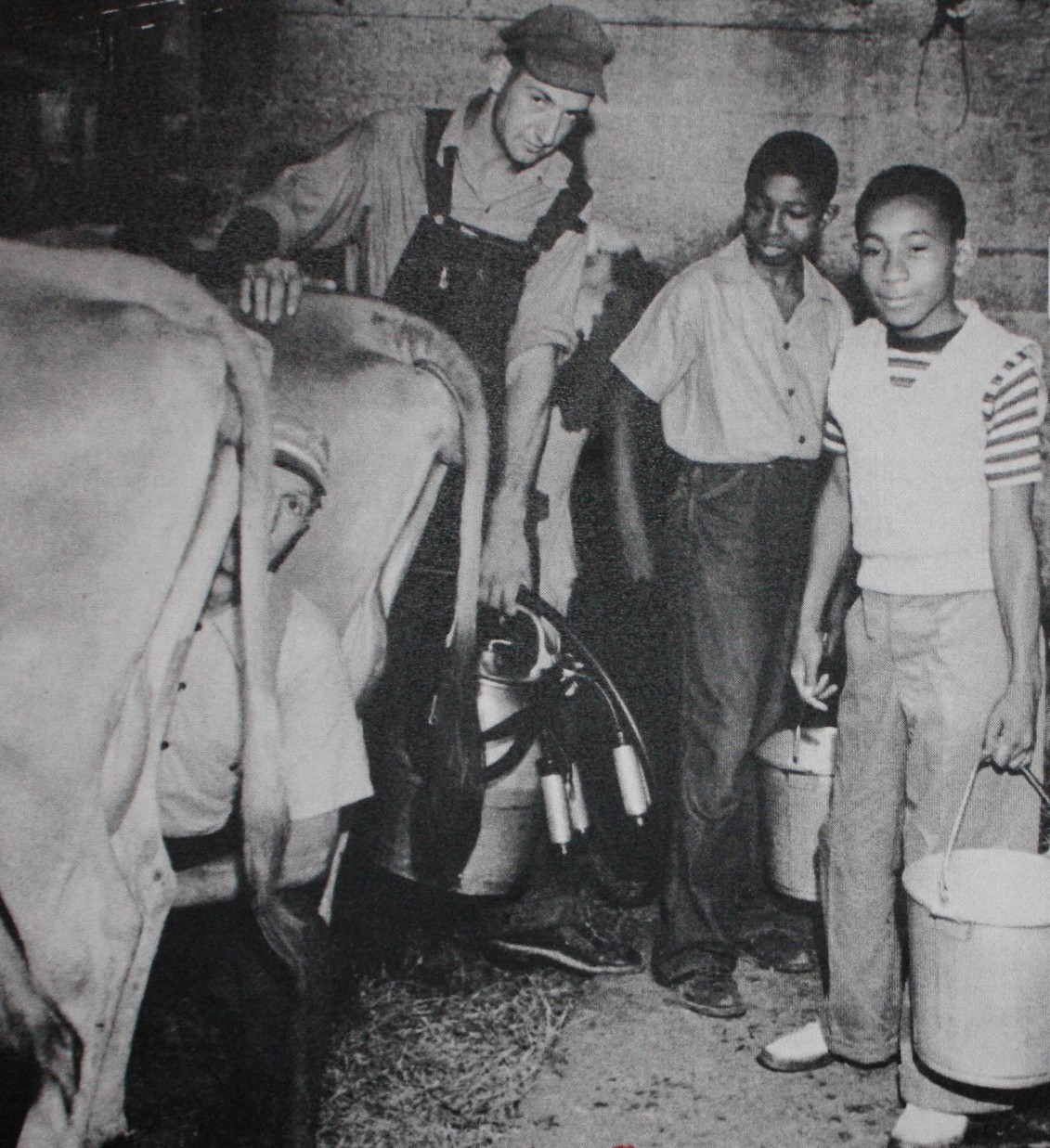

Two boys from Harlem pitch in at milking time on a Hinesburg, Vermont farm/New York Public Library, Schomburg Collection

Two boys from Harlem pitch in at milking time on a Hinesburg, Vermont farm/New York Public Library, Schomburg Collection

Many hosts relished these intimate, home-based exchanges across racial lines. Arnold Nickel, a pastor and host from Moundridge, Kansas, even claimed in 1961 that bringing urban children into his community did more to quell racial tensions than the Freedom Riders – activists who faced violence and intimidation while integrating interstate bus travel in the South. “We work toward creating better relationships and better understandings,” he said.

Some guests had such positive experiences that they eagerly returned when invited. Despite dealing with awkward questions about their home life, they enjoyed the chance to travel, swim in backyard pools and try new foods.

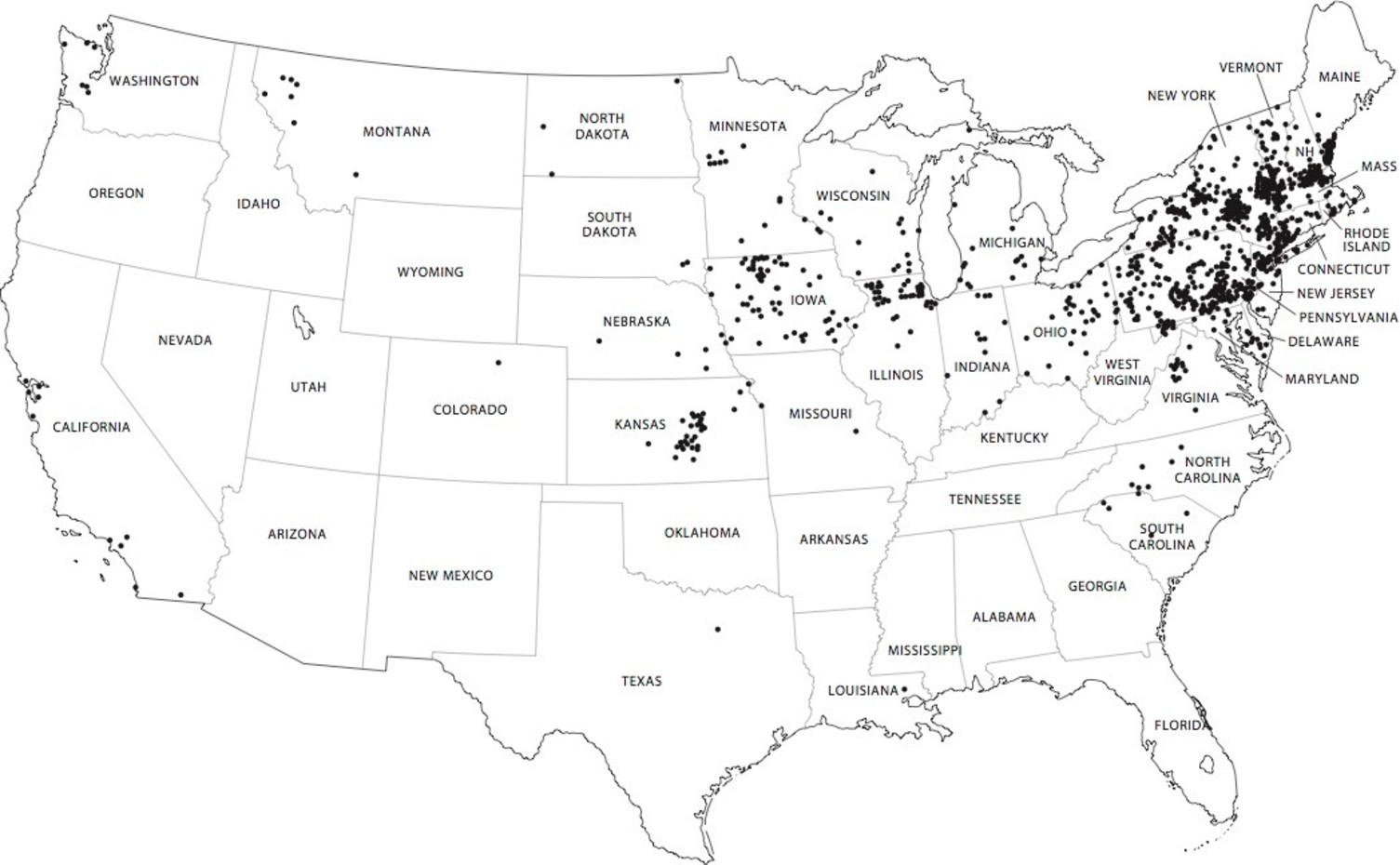

This map identifies more than 1,100 Fresh Air hosting sites active between 1939 and 1979, drawn from archival sources, newspaper accounts and publicity materials/Map designed by Bill Nelson, based on data compiled by Molly Williams, CC BY-ND

This map identifies more than 1,100 Fresh Air hosting sites active between 1939 and 1979, drawn from archival sources, newspaper accounts and publicity materials/Map designed by Bill Nelson, based on data compiled by Molly Williams, CC BY-ND

Our Interviews

My team interviewed and collected memoirs from nearly 50 former hosts, guests and program administrators who participated in the program in the mid-20th century. Those interviewed represented the major sending communities including New York City, Chicago and Philadelphia and popular hosting sites. Their stories confirmed what we found in thousands of letters and other documents. Nearly all the hosts and administrators we interviewed were white, consistent with the program’s demographics back then. Although we interviewed a few white former guests, most – also reflecting the demographics – were African American and Latino, and personally recalled instances of racial tension and overt racism.

Throughout this research, the Fresh Air Fund denied me access to its records, so I relied instead on thousands of regional newspaper reports, oral histories and other archives. Asked to address the Fund’s racial history, its director declined, saying, “We have never been about race.”

All 15 of the African-American former guests we interviewed remembered their hosts committing some form of racial harassment, expressing prejudice or being naive about bigotry. Most of the former Latino guests had similar experiences, but not the white children – even those with strong ethnic identities.

I frequently give lectures about this research at academic conferences and universities. Interestingly, audience members always tell me that they or people they know who took part in the program as guests in the 1980s or later also encountered overt prejudice and racial naivete.

Coping Mechanisms

Many kids of color taking part in the Fresh Air programs told their friends who later participated what to expect – and how to deal with racial epithets. For example, Thomas Brock, an African-American man who took part in the program while growing up in Virginia in the 1950s, recalled playing ball with the children in his host family as they called him the “N-word.”

Not only did Chicagoan Janice Batts have to deal with feeling like she was at a “slave auction” when the white Iowan hosts came to pick up the tag-wearing African-American children in the 1960s and 1970s, her host siblings would ask questions like “Why is your nose so wide? Do you sunburn? Why is your hair curly?”

She experienced severe trauma as well; a host father sexually abused her over the course of two consecutive summers. After a series of sexual abuse lawsuits in the early 1980s, the Fresh Air Fund finally began to vet hosts to screen out potential abusers.

Another concern to many of the people who participated in the program as children in my study – a concern that Fresh Air alums who took part in the program more recently have shared with me – was the assumption that, because they were from the city and nonwhite, they were not “equal” to their rural host families.

For example, Cindy Vanderkodde, a Fresh Air guest from New York hosted by a Michigan family in the 1960s, remembers thinking at the time, “Oh wow, this is family, they love me.” But when she moved into the hosting community a dozen years later as a college-educated social worker, things changed. “Once I became an equal . . . there was just no interest there,” she told me.

Some Progress?

Fresh Air Fund administrators told me that hosts today rarely disparage the nonwhite children staying in their homes and that more nonwhite hosts take part in the program. Images of white families hosting children of color, however, dominate its website. More importantly, the model remains unchanged: short-term, one-way exchanges billed as rescuing kids of color from the inferior conditions of their urban life.

As psychologist Gordon Allport articulated in what he called a “contact hypothesis” in the 1950s, social scientists have long recognized that short-term contact between disparate groups can actually reinforce stereotypes and prejudices when participants are not on equal terms.

Tennis player Althea Gibson shows two New York City children the first tennis racket she used in 1942, in the summer of 1973. Participation in Fresh Air ventures has declined in recent years, partly due to growing numbers of urban-based alternatives/AP Photo, CC BY-NC

Tennis player Althea Gibson shows two New York City children the first tennis racket she used in 1942, in the summer of 1973. Participation in Fresh Air ventures has declined in recent years, partly due to growing numbers of urban-based alternatives/AP Photo, CC BY-NC

In 1971, a black nationalist critic of the program, John Powell, called for a complementary “stale-air” program and suggested that Fresh Air ventures be “terminated” because its racially paternalistic assumptions were a recipe for failure. Most of these programs folded because of this kind of criticism, changes in family dynamics with host mothers increasingly working outside the home, and urban alternatives like free day camps. The Fresh Air Fund is by far the largest and most robust of the few remaining.

Despite their good intentions, I don’t believe that one-way, short-term cultural exchanges like the Fresh Air programs can wipe racism off the map – especially given the economic and social gaps between the segregated communities in which we live.

Tobin Miller Shearer is an associate professor of history and the director of the African-American Studies Program at the University of Montana. This article was originally published on The Conversation.

–

Comments welcome.

Posted on June 26, 2017