By Joshua Schneyer and M.B. Pell/Reuters

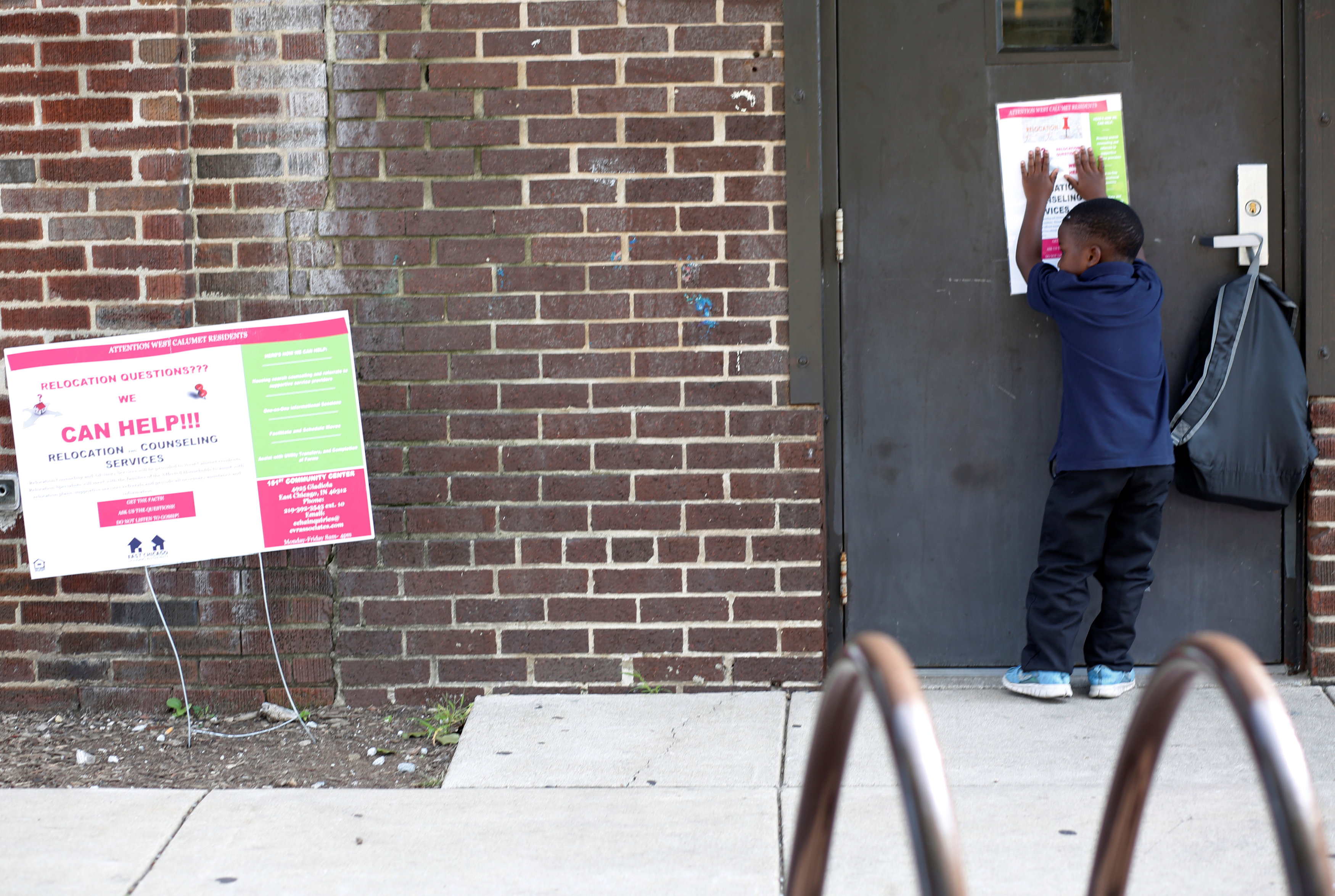

EAST CHICAGO, Indiana – In this industrial Northwest Indiana city, hundreds of families who live in a gated public housing community with prim lawns and a new elementary school next door are searching for new homes. Their own places have been marked for demolition.

The school, temporarily closed, has been taken over by the Environmental Protection Agency and health officials who offer free blood tests to check residents for lead poisoning. Long after the U.S. lead industry left East Chicago, a toxic legacy remains. Smokestacks at one smelter next door, shuttered 31 years ago, for decades polluted these grounds.

Emissions from the now-defunct U.S. Smelter and Lead Refinery Inc., or USS Lead, left a potent hazard in the soil. By early this year, the EPA detected concentrations of the heavy metal so high in some yards that they could pose a serious health risk to families at the West Calumet Housing Complex. Children are told not to play outdoors.

At the 44-year-old housing complex, all 1,100 residents are being forced to move out. Many are outraged about why the dangerous soils weren’t identified and removed earlier.

One reason: Five years ago, a unit of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a 19-page report that all but ruled out the possibility of children here getting lead poisoning.

–

Yasir, 5, resides in the West Calumet Complex in East Chicago, Indiana/All photos Reuters, Michelle Kanaar

(ENLARGE)

(ENLARGE)

–

That CDC branch – the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, or ATSDR – conducts public health assessments to examine potential contamination risks and point the way to next steps to be taken by EPA and others.

In its January 2011 report, ATSDR said it reached “4 important conclusions.” Among them: “Breathing the air, drinking tap water or playing in soil in neighborhoods near the USS Lead Site is not expected to harm people’s health.”

ATSDR’s report was built on flawed or incomplete data, a Reuters examination found: The assumption that residents weren’t at risk was wrong, and many of the report’s key findings were unfounded or misleading.

The report said “nearly 100 percent” of children were being tested for blood lead levels in the impacted area. State data reviewed by Reuters show the annual rate of blood lead testing among children in East Chicago ranged from 5 percent to 20 percent over the last 11 years.

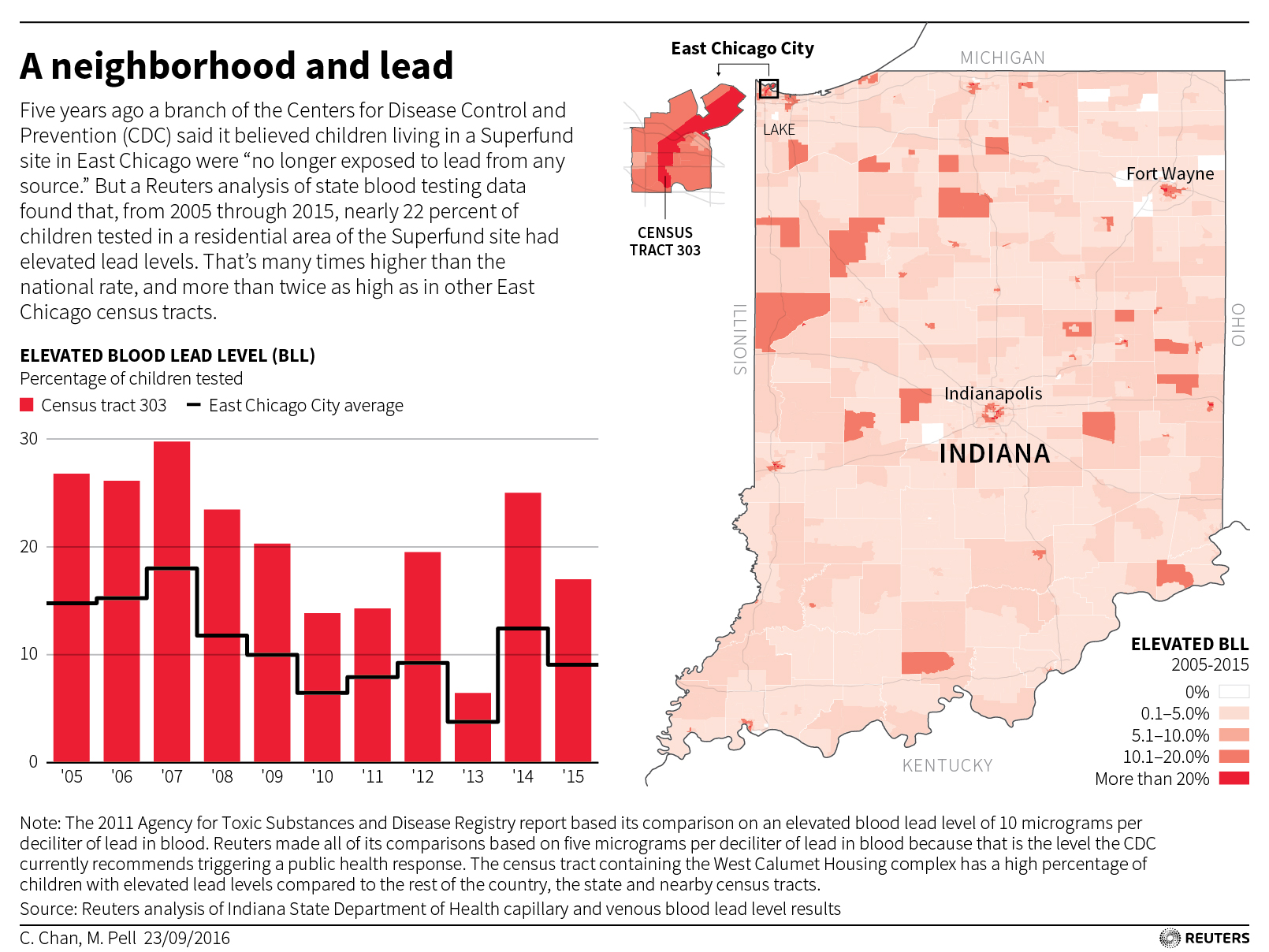

In the area, well known for its history of lead contamination, ATSDR reported that “declining blood lead levels in small children appear to confirm that they are no longer exposed to lead from any source.”

Yet from 2005 to 2015, nearly 22 percent of children tested in the Indiana census tract that contains the West Calumet houses showed an elevated blood lead level – 160 such results in all. Children tested in this tract were more than twice as likely to have an elevated reading than in other areas of East Chicago, state data reviewed by Reuters shows.

The CDC’s conclusions help explain why many West Calumet residents didn’t learn until recently that their yards were toxic, according to health experts, city administrators and data compiled by Reuters.

–

A Neighborhood and Lead

(ENLARGE)

(ENLARGE)

–

Carla Morgan, East Chicago’s city attorney, believes the report contributed to a false sense of safety.

“In 2011, the ATSDR lacked data to make any conclusion about the potential health risks,” Morgan said.

Contacted by reporters, the ATSDR initially said it would respond to detailed questions about its 2011 report. Over a period of weeks it said it was finalizing its responses. A spokeswoman, Susan McBreairty, told Reuters the answers were “complicated.” Reporters also sought comment from the two ATSDR scientists listed as authors of the 2011 report; neither responded.

Ultimately, ATSDR didn’t address the questions.

Instead, it released a broad media statement Thursday saying it is evaluating new EPA data “to determine if a human health hazard has developed since the Agency’s 2011 public health assessment (PHA) of the USS Lead and Smelter site.”

A new analysis will come next year, ATSDR said in the statement, and “will help determine if additional public health activities are warranted.”

BARRIER BETWEEN CHILDREN, SOIL

The report’s findings factored significantly into EPA’s decision not to conduct more urgent soil testing or urge residents to relocate, said EPA Region Five Administrator Robert Kaplan. Believing residents weren’t at imminent risk, EPA focused on a multi-year plan to gradually test for and replace lead-tainted soil.

Once EPA completed its soil-sampling this year, the scope of the danger for children was clear.

“The high levels of lead in many yards in East Chicago would require a barrier to be placed between children and the soil, to protect them,” said Dr. Helen Binns, a pediatrician at Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago and professor at Northwestern University’s medical school, who reviewed the testing data with Reuters.

EPA’s sampling found that 50 percent of the West Calumet homes tested had lead in their topsoil exceeding 1,200 parts per million, or three times the federal “hazard” level for residential areas.

That level warrants “time-critical” removal action within six months to protect human health, EPA standards say. In the most polluted yard found, a top layer of soil had 45,000 parts per million of lead.

Patrick MacRoy, a former head of the lead poisoning prevention program in Chicago, expressed shock after reviewing the ATSDR report. He found especially troubling its conclusion that children faced no threat of lead exposure.

“I can’t believe anyone with any degree of training or familiarity with environmental health would ever make (that) statement,” MacRoy said. “I can’t believe that no one reviewing that report internally, or even at EPA or the state, wouldn’t have flagged that as grossly misstating the available evidence.”

“I generally respect ATSDR, but that report is embarrassingly bad,” he said.

–

Industry and Housing

(ENLARGE)

(ENLARGE)

–

In recent months, 10 children under age 7 at West Calumet houses or in nearby areas were confirmed to have elevated lead levels, or around 5 percent of those tested, according to Indiana’s State Department of Health.

Following the notorious lead contamination of the drinking water supply in Flint, Michigan, around 4.9 percent of children tested there had high blood lead levels.

In East Chicago, more monitoring is planned, and the recent results do not mean children are in the clear, experts said.

Blood lead testing is usually indicated for children ages one and two. Ingesting lead-tainted soil, dust or paint chips is most common among infants and toddlers with hand-to-mouth behavior, said Dr. Bruce Lanphear, an expert on neurotoxins at Simon Fraser University.

A child poisoned at age two will often later test within a normal range. But the earlier exposure may have already wrought irreversible damage, including lifelong cognitive impairments.

‘WHAT ARE THEY DIGGING FOR?’

Today, outside the orderly brick houses in the community – due west of Gary, Indiana, and some 23 miles south of Chicago – moving vans are parked, and poster board signs warn residents not to play in the dirt.

Some of the 92 EPA staffers on site go door-to-door to speak with residents, offering testing and clean-up for lead inside their homes. Contractors have placed mulch over exposed dirt areas.

–

Don’t play in the mulch and dirt that’s covering up the lead.

(ENLARGE)

(ENLARGE)

(ENLARGE)

(ENLARGE)

–

The forced exodus of tenants comes after East Chicago’s mayor told them this summer that lead and arsenic contamination in the area made it unacceptably risky to live here, especially for the area’s more than 600 children.

“I have lived here for five years and was never told anything about contamination until now,” said Akendra Erving, a mother of five young children who is moving her family to Alabama. “In May or June, I started to see these crews digging in peoples’ yards. ‘What are they digging for?’ I thought.

“Now I know.”

–

A’Kendra Erving in her home with her son, King Erving, 3.

(ENLARGE)

(ENLARGE)

–

Recently, Erving got more bad news. A test showed that her three-year-old son, King, had a blood lead level of 8 micrograms per deciliter. Her daughter Kelis, 4, tested at 9 micrograms per deciliter. CDC recommends a public health response for children who test at 5 or above.

The lead crisis is the focus of several agencies, including ATSDR. The EPA has taken a leading role, with Indiana’s State Department of Health, city officials, state environmental officials and federal and local housing agencies also involved.

Tensions and finger-pointing among the parties has sometimes grown heated. In July, East Chicago’s mayor wrote EPA a scathing letter, accusing the agency of withholding soil testing data that demonstrated grave health risks.

EPA’s Kaplan says the soil data was shared with the city as soon as the EPA could verify it, in May.

Recently, a “peacekeeper” division of the U.S. Justice Department, its Community Relations Service, stepped in to de-escalate conflicts.

ON TOP OF ANACONDA

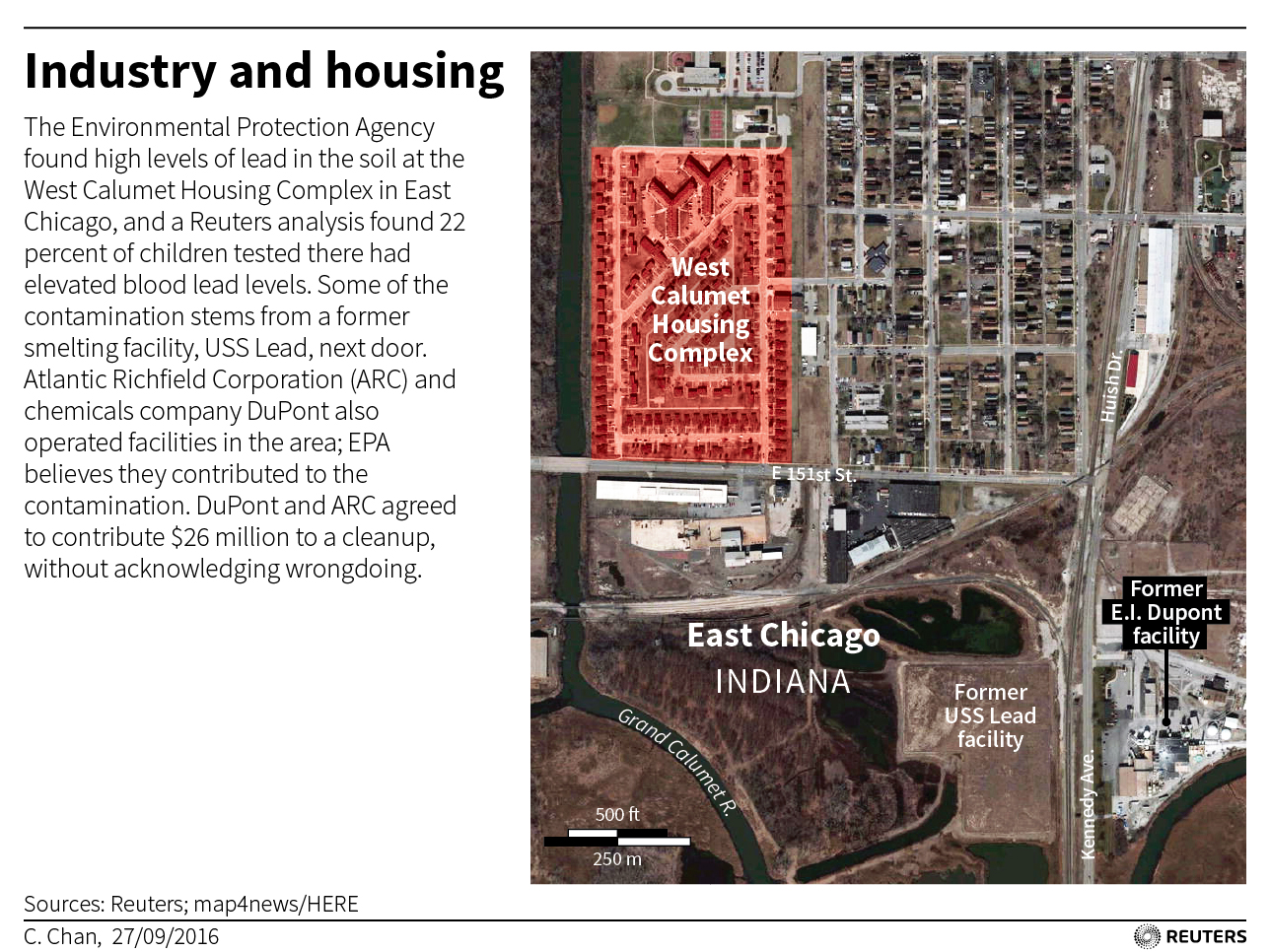

The West Calumet Housing complex stands near the center of a once humming U.S. industry hub. It was also a dirty one.

In the early 1970s, the houses were erected atop the former Anaconda Lead and International Refining Company. For decades, the plant churned out white lead pigment for use in paint.

In 1978, the United States outlawed the type of paint Anaconda produced for residential use. That and other measures brought a sharp drop in average U.S. blood lead levels in recent decades. No level of lead in the blood is safe for children.

Next door was another smelter, USS Lead. From 1920 through 1985, the facility refined lead or lead products. Its blast furnaces pumped out soot that blanketed the land where the housing complex stands.

Also nearby was a facility, formerly operated by chemicals giant DuPont, that produced lead arsenate from 1928-1949. Its main ingredients were lead and arsenic. The product was banned as an insecticide in 1988.

Much of the waste was stockpiled within the city’s industrial complexes. Sometimes it got spread over nearby marshland or dumped in the Calumet River.

Back in 2009, this corner of East Chicago, a working class city of 29,000, was placed on the federal Superfund’s National Priorities List, or NPL.

Michael Berkoff, an EPA project manager who led a 2012 public hearing in East Chicago to inform residents about clean-up plans, described the NPL as “EPA’s nationwide list of the most contaminated sites in the country.”

Numbering more than 1,300 nationwide, the Superfund sites require clean-up to protect the environment and human health. In many cases, the companies that used to operate them folded years ago.

At the hearing, Berkoff laid out EPA’s long-term goal of removing contaminated soil from West Calumet yards and other polluted zones in East Chicago. “Some of the contamination here is at higher levels than we would consider hazardous waste,” he told the audience, according to a transcript.

Years earlier, the EPA had already cleaned up several area yards where topsoil testing detected lead levels exceeding 1,200 parts per million, ppm.

The next round of remediation EPA proposed would cost tens of millions of dollars and take a few years, Berkoff said. At West Calumet, wherever EPA found yards whose shallow soil exceeded 400 ppm of lead, it would excavate and replace the layer with clean soil.

To fund the effort, EPA and the U.S. Department of Justice pursued what they called potential responsible parties for some of the area’s contamination. In 2014, chemicals company DuPont and ARCO, a unit of oil giant BP, agreed to contribute $26 million to the East Chicago clean-up.

Under a consent decree, the companies acknowledged no wrongdoing.

ARCO said it had taken on certain liabilities after it acquired the Anaconda Company in the late 1970s, though it never operated the Anaconda lead plant itself.

DuPont said it cooperated with the EPA but its responsibilities under the consent decree were assumed by the Chemours Company, a former DuPont business now operating independently, a DuPont spokesman said. Chemours said it will cooperate with the EPA, a spokesman said.

To date, the earth-moving envisaged in the plans EPA’s Berkoff described in 2012 hasn’t happened. Securing funds, soil testing, and issues that crept up with contractors all took time. West Calumet soil replacement would have started this summer, EPA’s Kaplan said. Instead, the city plans to raze the houses.

TROUBLED TRACT

The CDC’s role in ensuring the health of people near Superfund sites is enshrined in federal law. When an area is added to the National Priority List, the ATSDR conducts an independent public health assessment.

ATSDR’s role is advisory, but its reports can lead to strongly worded health bulletins or other actions, including condemnation of properties deemed unfit for human habitation.

The EPA commissioned the ATSDR report because “We wanted to know, is it an emergency, time-critical response or something that needs a remedy but isn’t necessarily as urgent?” said Kaplan.

The CDC branch concluded that results from childhood blood tests in the region suggested there was no risk.

Other report statements appeared to support that finding: Virtually all children in the area were being tested for lead poisoning, the report said, seeming to reflect close monitoring. Kids living in the area had blood lead levels “consistent with the national average,” it said.

Properties found to contain unsafe levels of lead in the soil had already been cleaned up by the EPA, the ATSDR said, and local health officials offered assurances there were no reports of health problems linked to lead.

Citing Indiana Department of Health data from the 1990s through 2008, ATSDR said children in East Chicago had experienced a sharp decline in blood lead levels.

Yet the report did not specifically cite the most recent blood testing data from residents at the West Calumet Housing Complex, or the census tract where it is located.

Reuters obtained testing data from the Indiana census tract, labeled 303, from 2005 through 2015. The data compiled by Indiana shows that 21.8 percent of children aged up to 6 tested there had blood lead readings above CDC’s current “elevated” threshold.

Although only a portion of the area’s children were being tested in the period, the 303 tract registered 160 elevated test results among small children. That was more than in any other tract in Lake County, where East Chicago is located, and more than in all but a dozen of Indiana’s 1,507 census tracts.

As recently as 2014, 25 percent of the children tested in the 303 tract had elevated levels.

During that same year, Indiana data shows, around 6.4 percent of kids tested across the state had elevated lead levels. CDC estimates show that, across the United States, the prevalence of children with elevated blood lead levels is around 2.5 percent.

The ATSDR report credited Indiana’s state health department with “excellent work” in ensuring almost universal testing.

State and county data reviewed by Reuters tell a different story. The annual rate of blood lead testing among children aged up to 6 in Indiana hovered around 7 percent in recent years. Although around 20 percent of children in East Chicago were tested each year between 2005 and 2010, the rate plummeted to 5 percent in 2014.

As for the ATSDR report’s claim that it had heard of no concerns from local health officials, City Attorney Morgan said the agency never consulted East Chicago’s health department, which declined comment.

The Indiana State Department of Health told Reuters it “does not support the conclusions of that report,” without elaborating.

UPROOTED TO NEVADA

Shantel Allen is a 28-year-old mother of five who has lived at West Calumet since 2011, the year of ATSDR’s report. Allen is moving her family to southern Nevada next month. The housing voucher the family received won’t cover the high costs of the move, she said.

In July, around the time Allen was told her current home faces the wrecking ball, she received a letter from Indiana’s health department. It said her daughter, Samira, 2, had tested positive for lead poisoning with a level of 33 micrograms per deciliter, nearly seven times the elevated threshold. That result, the letter said, was from a test conducted 17 months earlier, around Samira’s first birthday.

“I wanted to know how she was exposed to lead, when and where?” Allen said. “I wanted to know why I was only informed more than a year later.”

The state health department said privacy law does not allow it to comment on a specific patient’s case. However, it said local health departments have primary responsibility for conveying blood lead test results to family.

Since July, Allen has had all her kids tested. Two had elevated levels, she said.

Then, last month, Allen recalled an information packet she’d received from the EPA, dated from late 2014. She didn’t pay much attention to it back then, because she says she didn’t understand its implications. It said the agency had conducted soil testing in her yard.

Reading back the findings recently, she said EPA had detected lead at 4,510 parts per million in the top layer of her front yard, or more than 10 times the action level. Arsenic was found at nearly 13 times the action level.

It was the yard her older kids had always played in, often tracking in dirt to the apartment, where Samira would crawl around on the floor.

Another former West Calumet resident, Krystle Jackson, said she moved her family out in July after two of her children tested with elevated lead levels. Her son, Kavon, 1, had a level of 7. She relocated to her parents’ home in Cedar Lake, 40 minutes south, which is facing a potential bank foreclosure. Jackson worries she’ll be left homeless.

–

Krystle Jackson’s children, Kavon Jackson, 1, and Kaydance Jackson, 3, sleep in their parents house in Cedar Lake, Indiana.

(ENLARGE)

(ENLARGE)

–

The timing of Jackson’s move, weeks before hundreds of other West Calumet residents learned the complex will be demolished, made her ineligible for a voucher others are getting to move into public housing.

“The housing authority told me there was nothing they could do for me,” she said. “I just wanted to get out of the public housing because nobody could tell me why my kids were being exposed to lead.”

–

More Faces Of East Chicago.

Nayesa Walker in her home with her daughter Kaelynn Lott.

(ENLARGE)

(ENLARGE)

*

Maritza Lopez in her East Chicago home.

(ENLARGE)

(ENLARGE)

–

All links by Beachwood.

–

Previously: East Chicago Is Toxic.

–

Comments welcome.

Posted on September 28, 2016